Nine Things To Know About Household Water Debt

August 6, 2020

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

1. Household water debts are linked to economic hardship, home plumbing malfunctions, and the rising cost of municipal water.

To repair and upgrade aging infrastructure, water and sewer rates are rising faster than inflation and faster than incomes for those at the bottom of the economic ladder. Many older homes have plumbing that leaks, which can cause high bills. Combined, these factors have resulted in a situation in which an increasing number of households are struggling to pay their water bills. “We’ve seen more concerns expressed about trying to figure out ways to ensure that people have the service and can afford the service,” says Doug Scott, a water utility analyst at Fitch Ratings.

2. The Covid-19 pandemic most likely will increase household debt burdens.

The economic shock felt by tens of millions of people who have been laid off or furloughed in the last four months will be reflected in more late water bill payments. Even though many states and utilities suspended water service shut offs and late fees for households that couldn’t pay their water bills, those payments will eventually come due. Many of the jobless will still not be able to pay. “There’s no way to envision it not being a bigger problem than before,” says Greg Pierce, who researches water access and affordability as the associate director of the UCLA Luskin Center for Innovation.

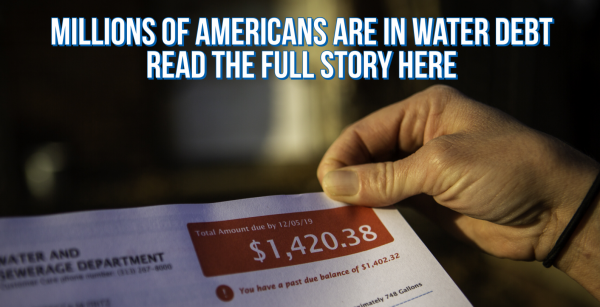

3. Household water debt can happen quickly.

An undetected leaking pipe can cause a monthly water bill to soar by several hundred or thousands of dollars. Some utilities will allow for a bill adjustment if the homeowner can prove the leak, but the process can be complex, time consuming, and so frustrating that people give up. “Once you get into a situation where your water bill skyrockets, it’s very hard to get out of that situation,” says Margaret Henn with Maryland Volunteer Lawyers Service.

4. Household water debt can accumulate slowly.

Many poor families are overwhelmed by bills for health care, utilities, rent, groceries, car payments, and other needs. One missed water bill, even for $40 or $50, can lead to another. And then another.

5. Debt leads to more debt.

Utilities typically tack on fees for a number of financial missteps: for late payments, for disconnecting water service, and for turning water back on. In cities where liens are used as a debt-collection tool, residents can accumulate additional fees if the lien is auctioned at tax sale. A lien gives the purchaser the right to collect overdue bill payments and levy a variety of fees. “It makes poor people poorer,” says Maria Quiñones-Sánchez, a four-term Philadelphia City Council member, about the effects of water debt.

6. Utilities are beginning to forgive debt and eliminate punitive fees.

San Francisco Public Utilities Commission discarded a $55 fee that was charged when water was shut off and then again when it was turned back on. The Atlanta Department of Watershed Management has periodic amnesties to wipe out fees that customers have accrued. Some city councils have required their utilities to be bolder. Utilities in Baltimore, Chicago, and Philadelphia are implementing programs that eliminate household water debts for low-income residents who enroll in assistance programs and make a series of on-time payments.

7. Water debt occurs in poor areas and wealthier neighborhoods.

ZIP code-level data from Detroit and Houston shows debt spread across poor, middle-income, and richer areas. Though debt has the greatest financial burden on low-income households, not all who owe money to the water department are poor. Some people behind on bills are merely forgetful or oblivious, which is why utilities argue that the threat of a shutoff is a necessary tool to compel payment.

8. The number of accounts that are past-due is not a complete indicator of the scale of the problem.

Atlanta recorded 46,133 past-due accounts at the end of the 2019 fiscal year, but 3,152 of those accounts owed less than $20. Utilities prefer to look at the percent of billed amounts that are not paid. Anecdotally, the industry average is about two to three percent, says Doug Scott of Fitch Ratings.

9. We know very little about household water debt.

Utilities are not required to post data on debt levels or the number of people affected. Comparing data across utilities is very difficult. Some utilities bill for water only, others for water and sewer, and still others include charges for services like garbage collection and stormwater. The quality of data collected by each utility varies widely. Utilities like the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department can identify debt levels by zip code. But others struggle to provide basic information such as the number of residential accounts that are past due. “We know so little about this question” of household water debt, says Manny Teodoro, a public policy scholar at Texas A&M University who focuses on water utilities.

Reporting for this article was supported in part by the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton