Brazil’s Covid And Water Crisis:

On The Front Lines With Photojournalist Tommaso Protti

On The Front Lines With Photojournalist Tommaso Protti

After a late entrance into the world of Covid-19, Brazil has become one of the new epicenters of the disease. As of July 6th, it has reported over 1.6 million Covid-19 cases, second in number only to the United States. The central government, led by President Jair Bolsonaro, initially denied the severity of the disease. Groups that support the country’s far-right leader rallied against quarantine and social distancing measures. The government has no health minister and attempted to block online information about the disease, a decision reversed by the Supreme Court four days later. Community groups such as G-10 favelas, which operates in the 10 largest informal settlements in Brazil, have stepped up in a time of need, providing services and aid. Tommaso Protti, an Italian photojournalist based in Brazil, described the situation for Circle of Blue reporter Sophia Petros.

When the virus first arrived, the majority of the people, including me, didn’t take it too seriously, because we didn’t have enough information. Then suddenly things started to get worse in Italy, it was declared a pandemic, and the media started to focus on it. Here, the response was “stay inside your house, try to start quarantining and social distancing,” but that’s never been imposed.

Here in São Paulo, more than 10,000 people have died. The virus was brought from outside, from people coming from Italy or the United States, so there’s always been the perception that the virus is a rich disease, brought from people who can afford the flights.

At the same time, quarantining and social distancing are just affordable for privileged people.

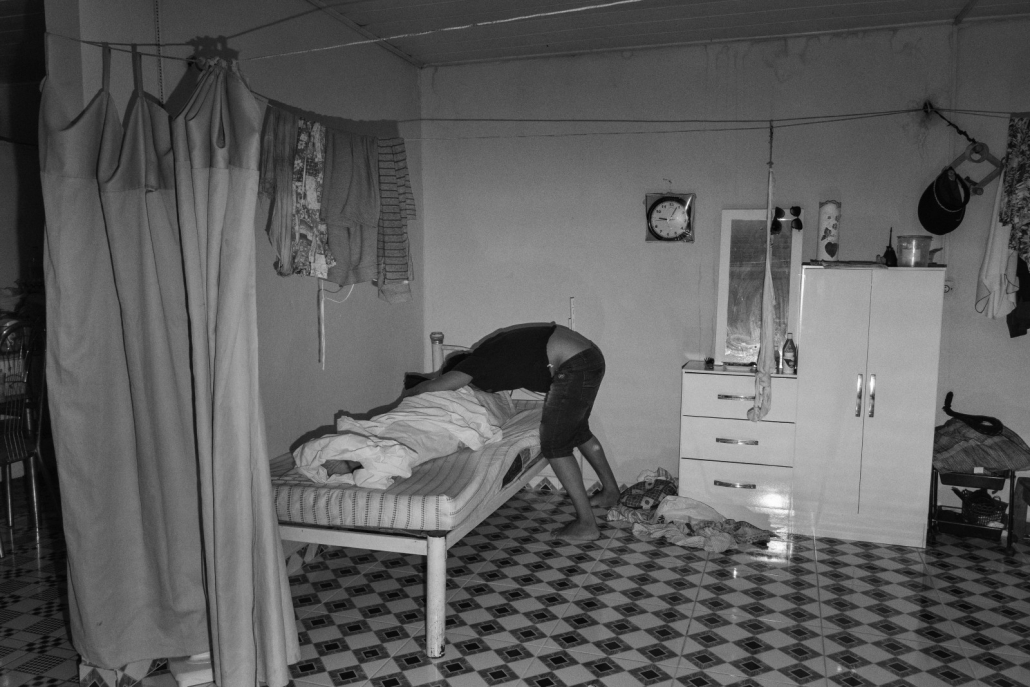

Brazil is an extremely poor country; there are a lot of inequalities. Millions of people live day by day, in informal communities, and they need to go outside to get jobs. Staying at home is not possible. Quarantining and social distancing are impractical in the peripheries, favelas, and slums.

The politicians had to choose: do we prioritize health or the economy? And they chose to prioritize the economy.

But what happened? Jair Bolsonaro, the president, embodies a mixture of negligence, irresponsibility, and self-interest. That is one of the reasons why Brazil has all of these deaths and infections. The government spread bad messages, like “this is just a little flu” or “if you have a sporty physique, you don’t have to worry about anything.” So you have this mix of things: favelas, peripheries, where you can’t practice quarantine or social distancing, and you also have the rich who follow Bolsonaro who didn’t, and still don’t, believe it.

It is becoming really, really bad because it’s a mixture of crises: the health crisis, the political crisis (really strong before the pandemic arrived), and the economic crisis (Brazil was already in a recession before the pandemic).

The lack of response is making it a humanitarian crisis.

The health structure and the hospitals are overcrowded. There are not enough IC units, and the central government started fighting with the governors, adding chaos to chaos.

MANAUS, BRAZIL – MAY 06, 2020: A relative prays from a distance at the burial of a Covid-19 victim at a Manaus cemetery. Due to the increased demand for burials, the cemetery is only allowing people to bury family members, and no more than five. The measure aims to prevent the risk of spreading the novel coronavirus. © Tommaso Protti for The Wall Street Journal

The water issue is central. To fight the disease you need to be clean, you need to wash your hands, and water is something that is lacking a lot in the peripheries. They often don’t have water for days, don’t have water to wash themselves or to clean the houses. But this is something that has been present for the people living in the peripheries forever.

There is a lack of structure for sanitation in many favelas.

The peripheries are huge, you have to distinguish between the slums, the shantytowns, and the other favelas where there are still houses. The architecture is quite different.

But in the classic way that we portray and think about a favela: Imagine shelters made of wood, of bricks — towns that have developed without any plans. You have some parts where you have pipes or tubes, but they are not connected with where the trash goes. The trash (and sewage) is accumulated really near the houses. The ground becomes contaminated. The water becomes contaminated. It’s all connected.

As long as the government doesn’t intervene, they will keep having the same problem.

The majority of the people try to accumulate the water in tanks that they leave in the upper part of the houses. But a lot of time the water doesn’t arrive through the pipes and it has to be brought with other tanks. Sometimes they just wait for it to rain to accumulate water.

MANAUS, BRAZIL – MAY 04, 2020: A relative grieves over the dead body of an 81-year-old woman suspected of being infected with Covid-19 who went into cardiac arrest and died in her home. The woman had felt severe chest pain and had breathing difficulties for several days, but refused to go to the hospital for fear of becoming infected with the coronavirus. © Tommaso Protti for The Wall Street Journal

At the beginning I started documenting things here in São Paulo. Then I went to Manaus, one of the main epicenters of the pandemic. Now it is a little more calm there, but I think Manaus is still the city in Brazil that has recorded the highest number of deaths per capita.

The situation was really tough there. All the structures present in São Paulo don’t exist there. The hospitals were overcrowded. There were a lot of people dying at home. Many people didn’t go to the hospital because they were afraid to get the virus in the hospital, but they had already had symptoms for days.

But the lack of information made the situation explode. Some people had breathing problems, or chest pains, but did not think they were feeling bad enough for it to be COVID. They didn’t want to go to the hospital, so they ended up waiting, waiting, and often ended up getting heart attacks or having cardiac arrest and dying at home.The main cemetery in Manaus tripled in efficiency since the outbreak. They had to resort to mass graves.

Then I went to another field hospital and some favelas in Rio and came back. I had to rest a bit because working with COVID is really stressful psychologically. You have to be really really careful. Especially when you travel a lot — the tension is double. I’m planning to go back to the Amazon region. The virus is spreading in some really remote areas.

For many indigenous tribes, this disease could be a massacre. They are attacked in a double way: the violence from the disease but also the violence from the illegal loggers who are taking advantage of the moment. Deforestation has increased exponentially this year — by 40% this May compared to the May of the year before.

You have to consider the virus as a pandemic from a health point of view, but you still have to see the context. Where this virus is taking place. This mixture of bad elements — lack of impunity, lack of social services, lack of political discipline — it’s become like a bomb.

When I took pictures inside the hospital, only one newspaper here had managed to get access. Getting to the hospital was important because it raised awareness about the situation.

I’ve always been driven by the importance of finding evidence of something. In 10 years, in 50 years, what will be important to remember from my historic point of view?

It’s important to gather complexity and cover as much as you can. With the pandemic, it’s important to show what makes the people pay attention. You need, in a cynical way, death or people suffering in the hospital. But then you have a lot of different kinds of suffering and different peripheries. I went to photograph food distributions for people who couldn’t go out and work because of quarantine.

Also I try to look from other angles. I went inside some churches to see how they were doing mass. Everyone was with their iPhone, like a web mass. It was something new for all of us to see.

Everything is still evolving. How are we changing our attitude and way of living and working? How will this pandemic change this society, change the attitude of the people?

I used PPE, the full plastic equipment suit, just when I went inside the hospital and ambulances, where there was a lot of risk. And at the beginning when I was entering houses with COVID patients. Actually, one of the first times up in the peripheries, the ambulance had to take a patient to the hospital and there was not enough space for everybody in the ambulance. I chose to stay in the favela and go back to the base myself. I was walking around like an alien, with all the PPE on.

I thought about that but I’ve never had this problem actually. I’ve been living in Brazil for many years now, so I speak the language fluently. They often think I’m from another state, not an actual foreigner. But even when it was really clear that I was a foreigner, a gringo, they never associated me as ‘a vector of infection.’ There was not this perception.

Prisons for sure. It’s a really dramatic place. We do not know a lot of what goes on there, but I have heard about death [from Covid-19] inside prisons. Brazil had the third largest prison population in the world. The prisons are totally overcrowded, with no sanitation.

The main problem of Brazil is lack of justice. This widespread corruption is everywhere, and it doesn’t allow real improvements to happen. This ends up deteriorating the whole society, economically, politically, and socially.

It’s that — impunity. It’s the country where you have the highest number of environmental and human rights activists and indigenous leaders, but then it’s one of the most violent places on Earth.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

© 2025 Circle of Blue – all rights reserved

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy

Torrential Rainfall and Flooding Hit Yemen Amid Conflict and Covid-19

Torrential Rainfall and Flooding Hit Yemen Amid Conflict and Covid-19This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to our use of cookies.

OKLearn moreWe may request cookies to be set on your device. We use cookies to let us know when you visit our websites, how you interact with us, to enrich your user experience, and to customize your relationship with our website.

Click on the different category headings to find out more. You can also change some of your preferences. Note that blocking some types of cookies may impact your experience on our websites and the services we are able to offer.

These cookies are strictly necessary to provide you with services available through our website and to use some of its features.

Because these cookies are strictly necessary to deliver the website, refusing them will have impact how our site functions. You always can block or delete cookies by changing your browser settings and force blocking all cookies on this website. But this will always prompt you to accept/refuse cookies when revisiting our site.

We fully respect if you want to refuse cookies but to avoid asking you again and again kindly allow us to store a cookie for that. You are free to opt out any time or opt in for other cookies to get a better experience. If you refuse cookies we will remove all set cookies in our domain.

We provide you with a list of stored cookies on your computer in our domain so you can check what we stored. Due to security reasons we are not able to show or modify cookies from other domains. You can check these in your browser security settings.

We also use different external services like Google Webfonts, Google Maps, and external Video providers. Since these providers may collect personal data like your IP address we allow you to block them here. Please be aware that this might heavily reduce the functionality and appearance of our site. Changes will take effect once you reload the page.

Google Webfont Settings:

Google Map Settings:

Google reCaptcha Settings:

Vimeo and Youtube video embeds: