https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/erik-mclean-susJsbx_3UQ-unsplash.jpg

1600

2400

Brett Walton

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Brett Walton2020-11-12 04:00:502020-12-07 10:12:06Overlooked Army Corps Rulemaking Would Shrink Federal Stream Protections

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/erik-mclean-susJsbx_3UQ-unsplash.jpg

1600

2400

Brett Walton

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Brett Walton2020-11-12 04:00:502020-12-07 10:12:06Overlooked Army Corps Rulemaking Would Shrink Federal Stream ProtectionsThe Year in Water, 2020

Societies Confront the Fallout from Rapid Environmental Change

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue – December 9, 2020

The warnings signs were visible, for those who wanted to see them.

Five years ago, the World Economic Forum asked its members to rank the calamities that posed the greatest threat to society. That year, in the middle of the Ebola outbreak in West Africa and while SARS-CoV-2 was still only circulating among bats, respondents deemed the spread of infectious disease the number two risk in terms of impact. The citizens of 2020, who have endured lockdowns, job losses, travel restrictions, and the deaths of friends and family during the pandemic, would surely agree. In retrospect they might even lift infectious disease to the top spot.

All years impose their discomforts. This year, in truth, stood out. Not just for the trials of the last 12 months. But as evidence of the tests yet to come.

What was the top-ranked risk in that survey of five years ago? Water crises.

Water crises, in many ways, are not like a pandemic, an event with a single, triggering cause. They are more diffuse and multi-faceted, and an individual crisis is usually constrained, not reverberating globally. But like the pandemic, water crises stem from environmental neglect and failures of leadership, and the repercussions of both are becoming more apparent every year.

2020 was no different.

Manmade systems were tested by supercharged weather and lax oversight. Water levels behind the Three Gorges Dam were the highest since the dam began impounding water in 2003. Operators were said to be on “wartime footing” to manage the inundation from a severe rainy season in southern China that caused an estimated $32 billion in flood damages.

The Three Gorges held, but structures elsewhere could not withstand mounting pressures. In Uzbekistan, the Sardoba Dam, completed just three years earlier, collapsed in May following days of rain. More than 100,000 people were evacuated. That same month in Michigan, two dams upstream of Midland failed during heavy rains. Soils were already saturated in the state, whose coasts were also besieged by record-high levels in lakes Huron and Michigan.

Shifts in water availability affected commercial infrastructure, too. In Panama, managers of the Panama Canal considered a range of water-supply projects to keep the vital shipping route viable during extended drought. To raise funds, the authority introduced new fees in February that apply to large ships using the locks in the waterway that connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Farther south, record-low water levels in the Parana River in Argentina resulted in ships running aground and cargo restrictions that limited soybean exports.

Not all was gloom, though. Water use in the American West continued its downward trend as conservation policies in the drying region paid off. A coalition of governments, businesses, tribes, and green groups pushed forward with tearing down four dams on the Klamath River of California and Oregon, in what will become the world’s largest dam removal. Lead service lines in Flint have nearly all been replaced. And the government of Denmark, though a small producer, set a 2050 timetable for ending oil and gas production from its North Sea fields.

Then there was the pandemic, which not only exposed the cracks in public health systems. It also laid bare the intimate bond between water, sanitation, hygiene, and health. Ensuring that households had adequate water during a health emergency was suddenly a top priority for municipal and national leaders. The governor of Michigan ordered all homes without water service to be reconnected, while the president of Ghana said the central government would cover the water bills of all residents for the months of April, May, and June.

All years impose their discomforts. This year, in truth, stood out. Not just for the trials of the last 12 months. But as evidence of the tests yet to come. Environmental challenges of water, climate, and health are real and growing — visible for those who want to see them.

Influential U.S. Government Actions

2020 turned out to be the final year of the Trump administration. It was a consequential and tumultuous four years. At the president’s direction, agencies set out to trim the federal rulebook. Water protections were among those regulations that were cut.

In the most significant action, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Army Corps of Engineers finalized in April a Trump campaign promise: to reduce the scope of the Clean Water Act.

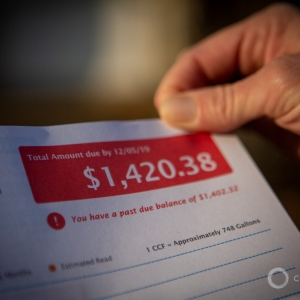

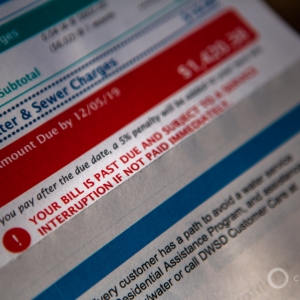

U.S. Water Access and Affordability

Despite the country’s wealth, running water and a working toilet at home are not assured for all people in the United States.

Though researchers found that there are more urban residents in “plumbing poverty,” rural areas also struggle with outdated water infrastructure, rising costs, polluted water, and declining populations. North Carolina continued its campaign to understand these financial stresses and direct state funds toward sustainable solutions.

Pandemic Puts Spotlight on Water Systems

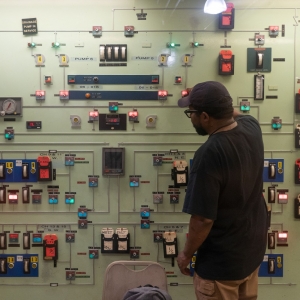

The coronavirus pandemic sent shock waves through all corners of society. Water systems felt them, too. Initially, utilities scrambled to ensure that the virus did not decimate their staff and leave no one to operate essential equipment.

Besides being an essential element of the public health response, water was instrumental in foretelling Covid-19 outbreaks. Testing sewage for traces of the virus provided a community-level snapshot of viral loads. Governments quickly embraced sewage surveillance as an early-warning system for cities, neighborhoods, and college campuses.

Covid-19 and WASH

The pandemic cast a sharp light on the connections between public health and the systems that provide safe water, sanitation, and hygiene.

To keep water flowing to households during the emergency, utilities stopped shutting off water for unpaid bills. In countries without widespread sanitation, aid agencies installed public handwashing stations and distributed soap.

Observers expect the social and economic consequences of the pandemic to influence international aid programs for years to come.

“The reality of this is you don’t have 150 million people drop into extreme poverty within a year without significant global consequences,” Liz Marcey, director of policy and advocacy for WaterAid America, told Circle of Blue.

Disasters Disrupt Water

It was another record-breaking year for natural hazards.

So many hurricanes barreled across the Atlantic that the World Meteorological Organization ran out of names on its alphabetical list and had to resort to Greek letters. Central America was struck by hurricanes Eta and Iota in November, the second being a Category 5 storm. Some of those uprooted by the twin disasters said they would leave home permanently and venture north, to the United States, foreshadowing future movement of people displaced by climate changes.

In the Pacific, the Philippines was hit by 21 tropical storms this year. Southern China endured more than four months of floods due to one of the strongest summer monsoons in recent decades. Water levels at the Three Gorges Dam were the highest recorded since the dam began impounding water in 2003.

Drought and heat were also supporting players in record-setting blazes in the American West, where wind-driven fires destroyed towns and water systems in California, Oregon, and Washington.

Technology and Adaptation

Meeting the challenges of this volatile era requires fresh approaches, some technical and some political.

States in the Colorado River basin reduced their reliance on the beleaguered river, their withdrawals dropping to 1980s levels.

Not all climate solutions are so simple. Researchers found that removing carbon from the atmosphere — either by mechanical means or by deploying grasses and trees at scale — drastically increases water consumption. Any fix to the world’s carbon and energy problems will need to keep an eye on the implications for water.

Climate Change Brings Water Risks

The year began with hellacious fires in Australia that burned more than 14 million acres in New South Wales, the largest blazes on record in the state. It was the culmination of a dry, hot summer Down Under in which rivers shriveled and towns had to rely on tanker trucks after they ran out of water. Then two months into the year, the skies opened up, dousing the fires but sending flood waters through the burn zones.

From floods and fires to food production, the consequences of a warming planet will be felt in changes to water supplies. Researchers in California and Hawaii found evidence that rising seas will worsen coastal flooding as groundwater levels rise in tandem with the ocean.

In heavily irrigated areas of the United States, the food trade relies on unsustainable groundwater use. California farmers are seeing that future play out now as water managers, in January, filed state-mandated plans for balancing groundwater supply and demand.

Bankers displayed alarm at the dangers of carbon pollution for the financial system. For the first time, the Federal Reserve included a section on climate risk in its semiannual financial stability report, warning that market collapses could occur. “Acute hazards, such as storms, floods, or wildfires, may cause investors to update their perceptions of the value of real or financial assets suddenly,” the report stated.

Water, Texas

The story of Texas is the state’s devout allegiance to the principle that mankind has dominion over nature. In 2020, the pandemic, climate disruption, and ever-present challenges with water supply and use are writing a much different story of vulnerability to nature’s bullying, and to government’s uncertain capacity to adjust.

In a five-part series, Circle of Blue explored the consequences of runaway development and tightening constraints on the supply and quality of fresh water in Texas.

HotSpots H2O

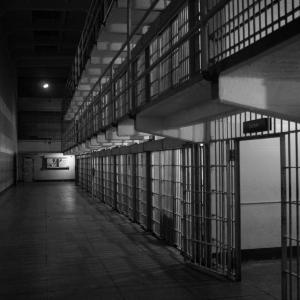

Water is both a source of tension and a casualty of war. In the end, it is the people who suffer.

Circle of Blue’s weekly HotSpots series highlights areas in which water access plays a role in civic upheaval and armed conflict.

Conflict unfurled this year on stages large and small. International mediators — the U.S. government and now the African Union — have attempted to soothe the current turmoil in Nile basin politics over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. Located on the Blue Nile, the dam is intended to electrify Ethiopia’s economic growth, but it also shifts the balance of power in a basin dominated for decades by Egypt.

Elsewhere, water systems were collateral damage in long-running conflicts in eastern Ukraine, Yemen, and Syria. Fighting in these areas resulted in setbacks for clean water provision and sanitation.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton