Virus Hunters Find Coronavirus Clues in Sewage

Wastewater analysis could provide an early warning of the spread of the new coronavirus.

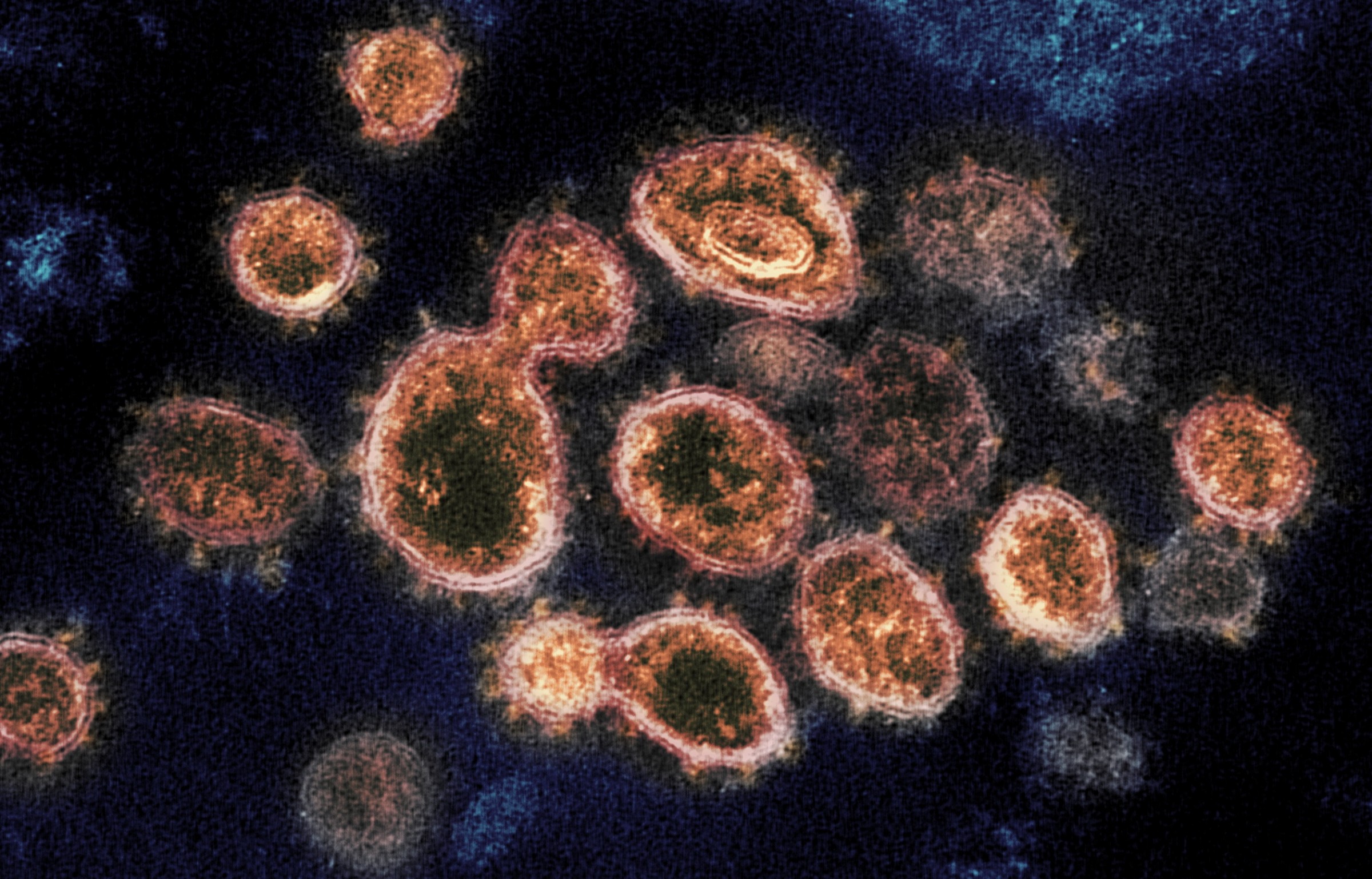

An electron microscope image of the SARS-CoV-2 virus. Photo NIAID-RML

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue

Even before it was confirmed by medical tests of infected individuals, the story of the new coronavirus in the city of Amersfoort was being recorded in water.

Scientists from KWR Water Research Institute in the Netherlands detected genetic traces of the SARS-CoV-2 virus in wastewater samples from Amersfoort’s sewage treatment plant on March 5, a day before the first confirmed case of Covid-19 in the city. Covid-19 is the disease caused by the virus.

That discovery, the researchers say, means that urban sewage systems could function as “a sensitive tool” for monitoring the spread of the virus thorough a city before it is detected in individuals. Similar sewage-sleuthing methods have been used to detect polioviruses or to assess illegal drug use.

How sensitive a tool? The study, which was published online before peer review, looked at wastewater samples from seven cities in the Netherlands and from Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport. Samples taken in the first week of February did not reveal any trace of the virus, but in the second round of sampling, on March 4 and 5, samples from four wastewater plants showed evidence. At the time, there were only 82 confirmed cases in a country of 17 million people. A rough estimate — based on the observed number of confirmed cases in the cities — is that a virus signal starts to show up in wastewater when between one and four people per 100,000 are infected. The range depends on the virus protein that was analyzed.

An early-warning system with this level of detail could provide government authorities with useful data about the potential for infection, said Zhugen Yang of the Cranfield Water Science Institute. It is especially difficult, for instance, to track the prevalence of cases in which infected people show only mild symptoms and thus do not get tested.

“If the sewage test comes back negative, there could be confidence that there is less risk of infection,” Yang, who focuses on biomedical diagnostics, told Circle of Blue.

“Perhaps then people can go outside for a break,” he added, referring to the potential lifting of stay-home orders that have been instituted by local and national governments in the United States, Italy, and elsewhere.

Stories in Sewage

Other organizations are jumping into sewage tracking, also known as wastewater epidemiology.

In the United States, the leading group is Biobot, a Boston-based startup founded in 2017. The tech firm is partnering with researchers at MIT, Harvard, and Brigham and Women’s Hospital to test wastewater samples for SARS-CoV-2 and incorporate the data into forecast models, making them more accurate.

“There is an incredible opportunity to use this technology to get ahead of and monitor the Covid-19 epidemic,” the company wrote in a Medium post announcing the project. “A wastewater epidemiology system that aggregates samples from wastewater treatment plants across the US would provide a real-time map of Covid-19 as it spreads to new places.”

Biobot’s call for samples has been so successful since it opened enrollment on March 17 that the company is at capacity and working hard to scale up, according to Mariana Matus, the company CEO and founder.

Matus told Circle of Blue that she launched the campaign with a goal of getting 100 utilities to participate. Within two weeks, the campaign “was already oversubscribed,” having fielded more than 130 requests from nearly every state, she said.

There are drawbacks to lab-based approaches. For Biobot, testing kits are sent to participating utilities, water samples are collected over a 24-hour period, and then returned to Biobot for laboratory testing. To see changes in viral loads, utilities are asked to send samples once a week. It’s a process that yields valuable data, but it takes time — an estimated three days from sample collection — and analytical equipment.

Yang, a water sensor specialist, would like to see broader deployment of portable paper-based tests. These devices, like a litmus test in concept but significantly more complex in practice, reduce the time and cost of testing. Yang has already used them to evaluate malaria in Uganda, but he said that substantially more resources would be needed to take a SARS-CoV-2 paper-based test from a lab concept to field use.

Knowledge about SARS-CoV-2, just a few months into the outbreak, is limited but growing rapidly. Initial findings were connected to the behavior of other coronavirus, such as the closely related virus responsible for the 2003 SARS outbreak.

Finding genetic traces in feces does not mean that those viral remnants are able to reproduce and cause additional infections.

Disinfection, either with chlorine or ultraviolet light, kills the virus, so it is not expected to be present after sewage is treated. SARS-CoV-2 belongs to a class of viruses known as enveloped viruses, a category named for the fatty coat that protects the inner genetic material. Disinfection has been shown to be particularly effective on enveloped viruses.

Treated sewage, at this point, does not seem to be a significant source of Covid-19 transmission, but the research field is moving quickly and looking into the virus’s ability to survive in raw sewage. Researchers in China were able to isolate a live virus from the feces of two Covid-19 patients. What that means for potential disease transmission is still being assessed.

“The data are very limited, but a few studies have detected viable virus in stool samples from a small number of patients,” wrote E. Susan Amirian, an epidemiologist at Rice University’s Texas Policy Lab, in an email to Circle of Blue. “The literature is evolving rapidly, so I have no doubt there will be more data available soon.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!