Cheese in the Desert: Why Mega-Dairies are Piping Water onto Oregon’s Shrub-Steppe

An environmental coalition is lobbying for a moratorium on mega-dairies, which have proliferated in a water-challenged area of northeastern Oregon

This piece is part of a collaboration that includes the Institute for Nonprofit News, California Health Report, Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism, Circle of Blue, Columbia Insight, Ensia, High Country News, New Mexico In Depth and SJV Water. It was made possible by a grant from The Water Desk, with support from Ensia and INN’s Amplify News Project.

By Dawn Stover – May 6 2021

Cody Easterday is still waiting for the Oregon Department of Agriculture to approve his application, submitted in June 2019, for a Confined Animal Feeding Operation near the city of Boardman (pop. 3,340), 165 miles east of Portland. Easterday, a 49-year-old rancher whose family owns a huge agricultural operation in Washington state, proposes to open a mega-dairy that would be the second-largest in Oregon. The Easterday Dairy would have up to 28,300 animals and use more water than most cities in the state.

The future of Easterday Dairy is in doubt, however. On March 31, Cody Easterday pleaded guilty to a “ghost cattle scam” that defrauded Tyson Foods and another company out of more than $244 million by charging for the purchase and feeding of animals that never existed.

The following day, a coalition of activists testified at an Oregon Senate Committee on Energy and Environment public hearing, voicing support for a moratorium on new or expanded mega-dairies in the state. Many of them pointed to the Easterday Dairy proposal, as well as an earlier dairy cited for hundreds of environmental violations at the same location, as reasons to hit the pause button on dairies housing 2,500 animals or more.

At least four other mega-dairies have settled in the area around Boardman and nearby Hermiston over the past two decades. They include Threemile Canyon Farms, which has about 70,000 Jersey cows and supplies 2.2 million pounds of milk daily for the manufacturing of Tillamook products familiar to all Oregonians and an expanding national consumer base. Threemile is Oregon’s largest dairy operation and one of the two largest in the United States.

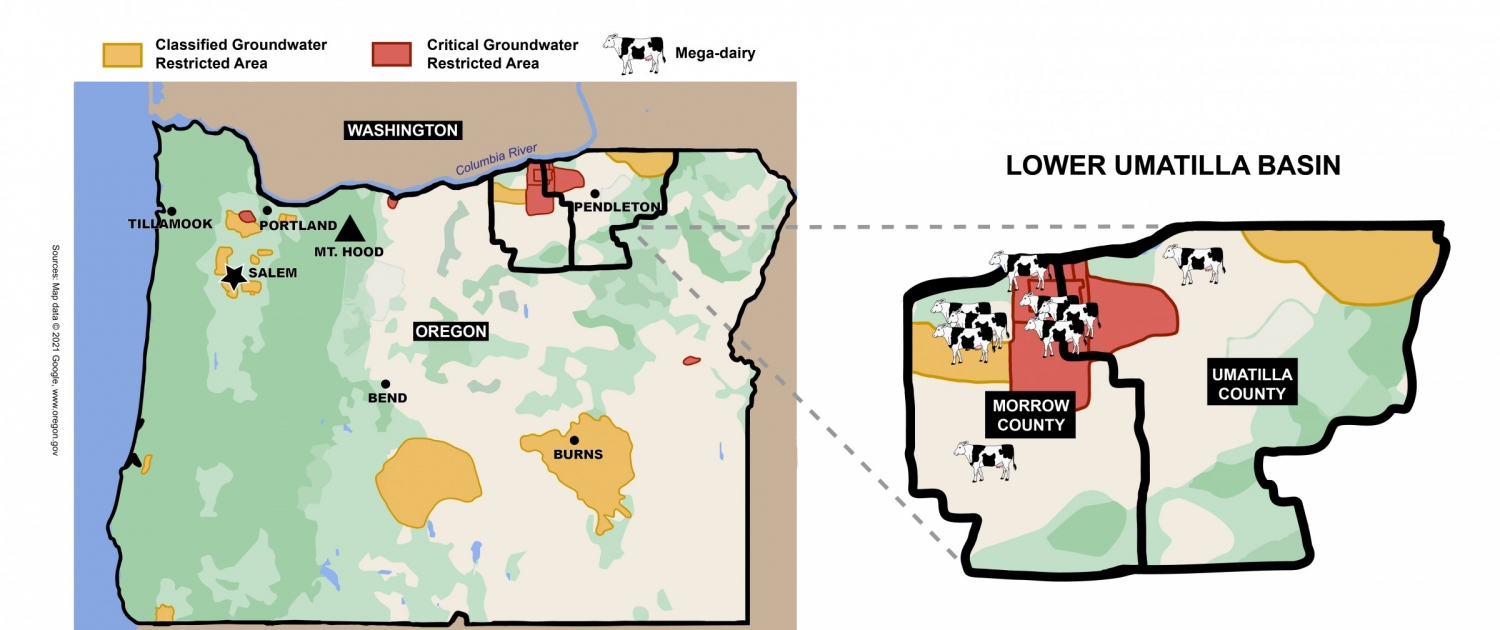

This part of northeastern Oregon, known to water managers as the Lower Umatilla Basin, is a region that sees less than nine inches of precipitation annually. It’s a desert that’s home to four of Oregon’s seven Critical Groundwater Areas, so designated because of water supply problems.

The Lower Umatilla Basin is also a state-designated Groundwater Management Area, because of nitrate contamination typically associated with agricultural wastes and fertilizers.

Why are thirsty mega-dairies, many from out of state, drawn to a region where both water quantity and quality are threatened?

[bctt tweet=”There are no limits on the amount of groundwater dairies can pump for animals to drink.” username=”circleofblue”]

Despite being home to four of Oregon’s seven Critical Groundwater Areas, the Lower Umatilla Basin has become a magnet for mega-dairies such as Meenderinck Dairy, which began operations here in 2012. Critics contend mega-dairies are attracted to Oregon’s lax regulations compared with neighboring states. Oregon doesn’t regulate air pollution from dairies, for example, even though dairy emissions contribute to climate change and exacerbate haze in the nearby Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. Photo by NASHCO

Using more water than cities

Surprisingly, mega-dairy farmers see the arid part of Oregon’s environment as a feature, not a bug. The Umatilla Basin is a place where enormous volumes of liquid manure and wastewater can not only be spread on flat, dry land with little danger of running off into nearby streams, but also used to grow profitable vegetable crops as well as feed for cows.

“Mega-dairies put enormous, concentrated demands on Oregon’s water resources,” says Brian Posewitz, a staff attorney at the Portland-based conservation group WaterWatch, who testified at the recent hearing. The proposed Easterday Dairy “would use about 20 million gallons of water per day on an annual average, and that’s by their own estimates,” Posewitz says. “To put that in perspective, the city of Bend’s (pop. 100,000) municipal water supply system uses about 12 million gallons of water a day.”

Dairies require drinking water for cows—about three gallons of water for every gallon of milk produced—as well as water for operations such as washing barns, cleaning equipment and misting cows to keep them cool.

But the biggest water demand at the mega-dairies in the Boardman area is for water to irrigate croplands surrounding the dairies. This land produces high-value vegetable crops such as potatoes and onions, as well as alfalfa and triticale for cows.

The land also plays an essential role as a waste disposal site. Easterday Dairy expects to generate more than 40 million gallons of liquid manure and more than 88 million gallons of wastewater annually—enough to fill almost 200 Olympic-size swimming pools.

Dairies in the Lower Umatilla Basin get their water from one or both of two sources: groundwater pumped from wells drilled into the desert floor; and surface water piped from local creeks and rivers, namely the Columbia River. Both face constraints.

The damming and diversion of rivers has been detrimental to salmon and other fish throughout the Pacific Northwest, and the Lower Umatilla Basin is no different.

But the Lower Umatilla stands out for its history of over-pumping groundwater. In the absence of groundwater studies, the state continued to issue groundwater rights in the basin until the early 1990s, when it became obvious that those rights could not be satisfied.

The aquifers in the basin had become so depleted that the state had to create four Critical Groundwater Areas that are now tightly regulated.

Some wells have been drawn down 500 feet or more. Most tap into basalt aquifers formed by ancient lava flows, which are productive for a while but recharge slowly if at all.

Data from nine observation wells in the deep basalt aquifer near Easterday Dairy suggest that water levels there have continued to drop over the past five years, even in wells that are not being used. “There is not good news in the water level trend,” wrote a hydrogeologist with the state’s Water Resources Department in a September 2020 internal memo.

“There is a massive amount of agricultural development out there,” says John DeVoe, executive director of WaterWatch. “They’re mining water that is 20,000 years old or more.”

Tillamook transplant

Despite its water woes, the Lower Umatilla Basin has become a magnet for mega-dairies. Stand Up to Factory Farms—a coalition of local, state and national organizations concerned about the impacts of these dairies—alleges that’s because Oregon has lax regulation compared with states such as California, Washington and Idaho.

Mega-dairies also exploit a loophole in Oregon’s water laws. A water right is required for most water uses, but the law has an exemption for stock watering, and there are no limits on the amount of groundwater dairies can pump for animals to drink.

A bill introduced this year in the Oregon Senate proposes to limit the exemption for livestock watering to 5,000 gallons a day, but it is stalled.

There’s another reason mega-dairies have come to the Lower Umatilla: a cheese factory.

The Willamette Valley and the state’s coastal area dominated Oregon’s dairy market until about 20 years ago. That’s when the Tillamook County Creamery Association—a cooperative owned by about 80 families that operates a well-known cheese factory in coastal Tillamook County—built a second manufacturing facility at the Port of Morrow in Boardman. Called Columbia River Processing, the unmarked, windowless plant is actually a Tillamook factory, recognizable for its stainless-steel milk silos and double-tanker Milky Way trucks parked outside.

Milk is Oregon’s official beverage and the state’s fourth most valuable commodity, worth about $552 million in 2019. Americans are drinking less milk than they once did but eating more cheese and yogurt made from milk.

The Tillamook factory relies on mega-dairies for its milk supply. Foremost among them is Threemile Canyon Farms, which sprawls across approximately 145 square miles—an area the size of Portland—southwest of Boardman. The farm, which sells all of its milk to Tillamook, also grows alfalfa, potatoes, onions, corn, peas, blueberries and other crops.

The farm is owned by the Fargo-based R.D. Offutt Co.—founded by Ron Offutt, the richest person in North Dakota. It uses a “closed-loop system” to recycle its own wastes—fertilizing fields with liquid and composted manure, feeding potato peels and other food-processing waste to cows, heating manure slurry in a digester tank to capture biogas that can be used for transportation fuel and using the digester’s dried leftovers as livestock bedding.

What makes all this possible is a partnership with Tillamook, which opened its Boardman cheese factory in 2001. Threemile Canyon Farms established its dairy that same year. Other mega-dairies followed: Sage Hollow Ranch, permitted for up to 8,700 cows, started building a dairy southeast of Boardman in 2009. The nearby Meenderinck Dairy, permitted for 3,000 cows, got up and running in 2012.

Meanwhile, many smaller dairies around the state have closed their doors, reflecting a national trend of consolidation in the industry. In 1974, there were more than 4,200 dairies in Oregon, with an average of 21 cows each. Today Oregon has 247 dairies, with an average of 877 cows each. Four large dairies in Morrow and Umatilla Counties account for almost 40 percent of Oregon’s 216,614 dairy cattle.

“Unchecked consolidation has led to geographical clustering,” says Tarah Heinzen, a senior staff attorney at Washington, D.C.-based Food & Water Watch.

Problem or poster child?

The Stand Up to Factory Farms coalition is now lobbying for a moratorium on mega-dairies.

The coalition fears the Easterday Dairy doesn’t have the resources to run a responsible dairy. They’re asking the state to deny Easterday’s application on the basis that it failed to disclose all relevant facts—specifically, that Cody Easterday has admitted to perpetrating a massive fraud and using the proceeds to cover his commodity futures trading losses, and that two other Easterday family enterprises, Easterday Farms and Easterday Ranches, have declared bankruptcy.

“It’s a serious concern that an applicant would withhold information,” says Heinzen.

The application is still under state review.

Although proponents have repeatedly proposed legislation to block permits for new or expanded mega-dairies, and the most recent Senate bill got a public hearing, there will be no further movement in the 2021 legislative session.

Opponents of the bill say a moratorium on mega-dairies would have a negative effect on what Paul Snyder, executive vice president of stewardship at the Tillamook County Creamery Association, describes as an industry “success story.”

As far as the industry is concerned, Threemile Canyon Farms (TMCF) is the poster child for best practices. The Innovation Center for U.S. Dairy named TMCF as one of three dairy farms nationwide to receive its 2020 award for Outstanding Dairy Sustainability, citing TMCF’s closed-loop system and high standards of animal care. The farm has set aside 25% of its land as a wildlife conservation area, managed by The Nature Conservancy, along with the water rights for that land.

TCMF says it adheres strictly to its goal of wasting nothing. The farm’s wastewater is collected and injected into the irrigation system. The amount of water delivered to crops is tailored to each field, and soil moisture is monitored in real time to prevent overwatering. Hoses hanging from the center-pivot irrigation system deliver low-pressure water through nozzles close to the ground, minimizing evaporation losses.

“What we’re able to offer is a level of sophistication of water management that not every farm is able to bring to bear, just because of the scale that we have and the resources that we have,” says Tara May, spokesperson for Offutt, the farm’s parent company.

Threemile Canyon Farms has two groundwater wells, each permitted to produce 2.7 cubic feet per second; this water is used for drinking water, flushing manure and other dairy operations. Irrigation water is pumped from the Columbia River through 231 miles of pipeline at rates up to 482 cubic feet per second.

Columbia River Dairy is one of multiple dairies around Boardman owned by Threemile Canyon Farms. Many Oregonians are unaware of the existence of mega-dairies, which are typically not visible from main roads, in this arid part of the state. Activists say mega-dairies exploit a loophole in Oregon’s water laws, which effectively place no limit on the amount of groundwater dairies can pump for animals to drink. Photo by NASHCO

Tapping the Columbia

But when it comes to water, Threemile’s “closed loop” is not entirely closed, despite the farm’s efforts to conserve water.

Once water is sprayed on crops, almost none of it returns to the river or local aquifers. Most is lost to evaporation or absorbed into the soil, then released back into the atmosphere as plants exhale water vapor, says Ivan Gall, field services division administrator for the Oregon Water Resources Department.

In an effort to reduce groundwater pumping in the basin and allow aquifers to begin recharging, farmers and state agencies have looked to the Columbia River for water. The Northeast Oregon Water Association, a nonprofit founded in 2013, recently succeeded in bringing together stakeholders to construct three pipelines that will provide Columbia River water as an alternative water source for growers in the Umatilla Basin. Two of the three pipelines became operational within the past year.

The water association negotiated a 30-year lease with the Port of Umatilla and other local entities that hold municipal water rights entitling them to more Columbia River water than they’re currently using. Transferring some of this water to agricultural uses did not require any new rights, but it does mean more water is being extracted from the river than was previously being used.

J.R. Cook, founder and director of the Northeast Oregon Water Association, says the Lower Umatilla Basin is an irreplaceable agricultural resource: its weather makes for a long growing season; its soil grows twice the tonnage of potatoes per acre as Idaho; its proximity to the Columbia offers a stable water supply; and its flat terrain makes it economically feasible to pump water over long distances. Mega-dairies extract maximum value from that water by using it twice.

“Our hope is that the big dairies will want to use the new pipelines in lieu of groundwater pumping,” Cook says.

Industrial vision

Supporters of a moratorium on mega-dairies remain unconvinced that farms like Easterday can ever be sustainable.

“Mega-dairies produce mega-pollution,” says Emma Newton, a coalition organizer for Stand Up to Factory Farms and Food & Water Watch.

Cody Easterday will be sentenced on August 4. His father, the patriarch of the Easterday agricultural empire, died in December when he drove the wrong way on an interstate near his office and collided head-on with one of his farm’s own trucks. Cody’s son, Cole Easterday, is reportedly moving forward with plans to open the Easterday Dairy.

He’ll need a permit from the state of Oregon, a contract to sell milk to the Tillamook factory in Boardman and a year-round source of water. History suggests he’ll find a way to get all of it. The state allowed the previous owner to open before the dairy had all of its water supply and waste-management systems in place, and that owner later drilled several wells without permits.

Dairy supporters say it would be unfair to penalize the state’s entire industry because of one bad actor (known as Lost Valley Farm) who did not comply with the rules.

“There is no environmental reason to ban dairies based on size,” said Mary Anne Cooper, the Oregon Farm Bureau’s vice president of public policy, at last month’s hearing on the proposed mega-dairy moratorium. “We fear that policy makers are eager to support the Pinterest-worthy farm that presents an idyllic version of agriculture.”

Dawn Stover is an independent journalist based in White Salmon, Washington, and a contributing editor at the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists.

Tapped Out: Power, justice and water in the West. This piece is part of a collaboration that includes the Institute for Nonprofit News, California Health Report, Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism, Circle of Blue, Columbia Insight, Ensia, High Country News, New Mexico In Depth and SJV Water. It was made possible by a grant from The Water Desk, with support from Ensia and INN’s Amplify News Project.

Related

© 2025 Circle of Blue – all rights reserved

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy