The Department of Health and Human Services still has not distributed $638 million that Congress appropriated at the end of December.

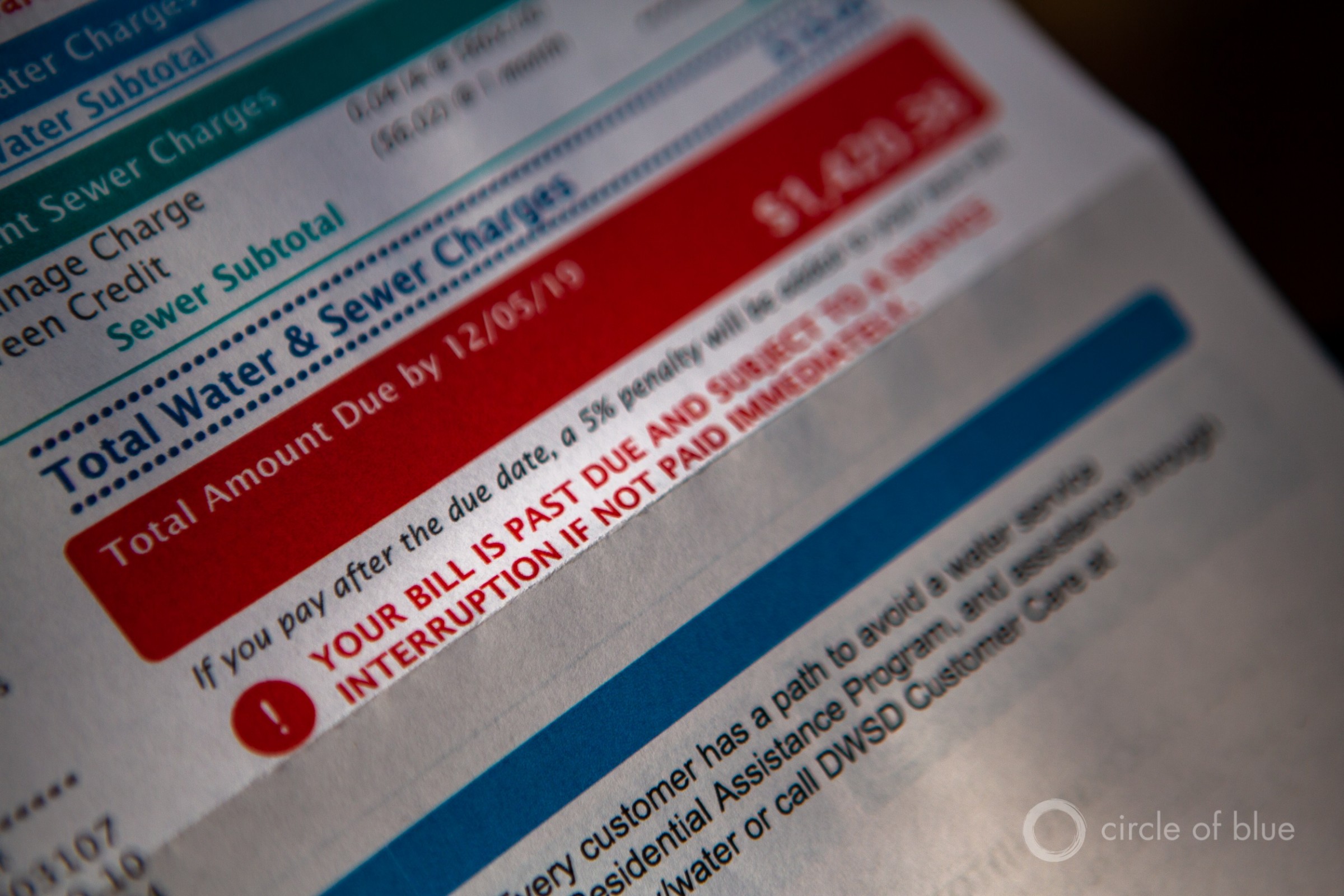

A resident of Detroit displays a past-due water bill. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

Key Takeaways

- For the first time ever Congress set aside more than $1.1 billion for low- and middle-income Americans to relieve household water debts amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

- The program has been met with delays due to a lack of administrative protocol and a streamlined process to ensure families in need receive funding.

- Behind the scenes, the battle to decide the long term design of the program is up for debate. While social justice advocates want the water program to stick around, Congress is not so sure.

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue — April 28, 2021

[bctt tweet=”Behind the scenes, the battle to decide the long term design of a program to relieve household water debts amidst the pandemic is up for debate.” username=”circleofblue”]

In December, when Congress completed the 2021 budget, lawmakers added to the package more funding to help low- and middle-income Americans withstand the coronavirus pandemic.

In addition to a second round of stimulus payments, lawmakers included $638 million for households that were behind on their water bills. It was the first time that Congress had set aside federal funding for that purpose.

Little more than two months later, Congress doubled down on the approach, adding $500 million to what is now officially called the Low-Income Household Water Assistance Program, or LIHWAP. In total, more than $1.1 billion will be available to relieve households of water debts.

That’s where the process has slowed. As of late April, none of those funds has been allocated to states, let alone distributed to families in need. State allocations, to be set by the Department of Health and Human Services, are based on poverty levels and high housing costs.

On a call with stakeholders on April 20, representatives from the department’s Office of Community Services said that they expect the initial $638 million to be disbursed to states, tribes, and territories by late May. The office is coordinating the federal part of the program.

In a follow-up email to Circle of Blue, DHHS said that there is no definite timeline yet for disbursing the $500 million that was added to the program in March. But allocating that money will go more quickly, the department noted, because the administrative foundation is already in place.

Sending the money to states, tribes, and territories is only the first step in the process. Those governments function as intermediaries for LIHWAP. They must then decide how to distribute their share of the funds to households in need.

How to do that equitably and swiftly will be a challenge, according to David Bradley, the chief executive officer of the National Community Action Foundation, a group that lobbies for local social services and anti-poverty agencies.

Bradley is concerned that the sheer number of water providers in this country — numbering close to 50,000 and having vastly different administrative capacities — will be an impediment to the program’s success.

“I worry about that mom-and-pop water authority not having the foggiest idea how to do this,” Bradley told Circle of Blue.

The Department of Health and Human Services is encouraging states to use existing procedures so that the money can be distributed quickly.

Existing procedures, for the most part, means using the administrative infrastructure for a federal energy-bill assistance program known as LIHEAP. The thousands of community action agencies that Bradley represents are the key cog for making the energy-bill program work. But even that long-established program serves only about one in six people who are eligible.

The process for distributing water-bill assistance is not as streamlined as the one for distributing stimulus payments. Congress approved the second round of payments on December 27, the same time as it authorized $638 billion for water-bill aid. If you had a checking account on file with the Internal Revenue Service, $600 was deposited in your account within two weeks.

Part of the tension for water bill-assistance is the design of the program. Is an emergency response to Covid-19? Or is it the beginning of a permanent program like LIHEAP? Office of Community Services officials emphasized the urgency of assisting people in a pandemic as quickly as possible. For that reason, the money cannot be spent on problems that might be causing high water bills, like plumbing repairs.

“We’re trying to save lives,” Lauren Christopher, the director of the division of energy assistance, said at the meeting, emphasizing that it is an emergency program. “We’re trying to keep people healthy and in their homes.”

Even so, DHHS is giving states until December 2023 to expend their funds.

Bradley said he has heard from several members of congressional appropriations committees that they see LIHWAP as temporary. “Not everyone is comfortable with making this a permanent program,” he said.

Social justice advocates and water sector groups, on the other hand, want the water program to stick around like the energy assistance program, which was established in 1981.

As those conversations play out in the background, there is front-line work still to accomplish.

[bctt tweet=”“We’re trying to save lives. We’re trying to keep people healthy and in their homes.” — Lauren Christopher, the director of the division of energy assistance at DHHS ” username=”circleofblue”]

After DHHS distributes the funds, local implementing agencies will determine how much each household will receive for water-bill assistance. But before states, tribes, and territories receive their allocations they must designate a lead agency to oversee the program. Even that has been delayed. The Department of Health and Human Services initially asked for lead agencies to be submitted by March 8. That deadline was extended to April 27. The department told Circle of Blue that a number of governments missed that cut off and have requested extensions to May 4. The department was not able to say how many are late.

“Timely access to grant awards, which is targeted to occur prior to the end of May, will be impacted by delays in submission that extend beyond May 4,” the department wrote in an email.

Not all of the $638 million will go to households. States, tribes, and territories are allowed to use 15 percent to administer the program.

Another development to watch, Bradley said, is the speed with which states use their funding. Bradley noted that some states were quite slow to expend funds from the CARES Act, which was approved in March 2020. The act included $1 billion for the Community Services Block Grant, but some states waited until February to hand out funds, he said.

“That experience haunts me about the water program,” Bradley said. “Will [DHHS] shovel it out the door and say, ‘Good luck’?”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton