Vineyards well watered, while people struggle for water.

By Sonja Smith

Located about 50 kilometers from the Noordoewer border post that separates Namibia from neighboring South Africa, Aussenkehr has vast vineyards that stretch as far as the eye can see.

Surrounded by a semi-desert area, the vineyards thrive only because of a plentiful supply of water from the nearby Orange River, which forms a natural border between the two countries. Set against the harsh, brown terrain, the verdant vineyards — which have grapes that can be harvested three to five weeks earlier than elsewhere on the globe — seem alien compared to southern Namibia’s dry and harsh landscape.

The highest average temperature in Aussenkehr is 34°C in January, and the lowest is 20°C in June. The area gets an average of 262mm of rain each year.

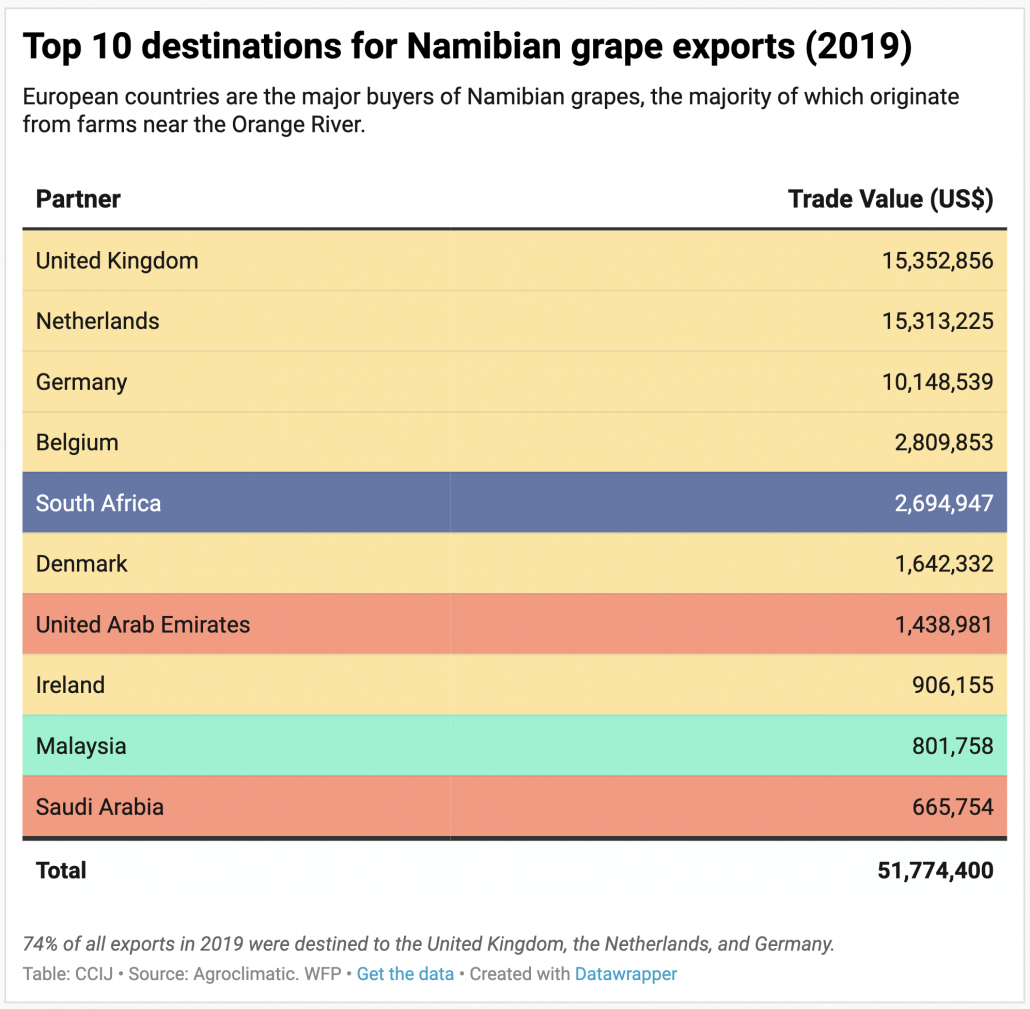

The plump and juicy table grapes that grow in these vineyards are destined for supermarkets in European countries, such as the Netherlands, Germany, and Belgium, as well as South Africa, generating much-needed foreign currency for Namibia. In fact, last year, all of Namibia’s table grapes exports earned N$840 million (US$56 million), and over 33 million kilograms of grapes were shipped out of the country.

But the oasis-like beauty of the area’s grape farms hides a dark secret: the 16,000 farmworkers who care for the vines and harvest the grapes earn a pittance and live under harsh conditions. Two kilometers from the grape farms, they live in an unnamed settlement in rudimentary reed and zinc structures, and have endured decades without potable water and other basic services like electricity and sanitation facilities. Residents even use the river and mountains as toilets.

A hilltop which residents are forced to use as a toilet. Photo: Brandon van Wyk

The Orange River is their lifeline, and they must fetch water daily from it for cooking and drinking. They also bathe and wash their clothes in it.

But the river is also dangerous, and at least 15 people have lost their lives in its deep and, at times, fast-flowing waters over the last 14 years.

Their dry and dour settlement stands in stark contrast to the rows and rows of bright green grapes that seem to stretch on for an eternity. It has no water to fight the fires that often spring up in the farmworker community, so residents can only stand and watch helplessly as their possessions and valuable documents are consumed by the flames.

It’s hard out there for a farmworker

Linda Christian, 29, a farmworker at Silverland Riverside, one of the Aussenkehr farms, described the harsh existence of the area’s grape-farm workers.

“I have been working here since 2011 as a seasonal worker,” she said. “We live in dwellings that have no proper structures. We do not have access to clean water, and there is no electricity. The farm companies bring water to permanent workers only, so for us to get water we have to go through the permanent employees,” Christian said.

Julian Swartbooi, 36, an employee at Silverland since 2019, adds, “We go by the river to bathe, wash clothes and fetch water for cooking and drinking.” They can access a very limited amount of clean water 300 meters away but there is “normally not enough to cater for everyone to use.”

Apart from a lack of clean water, Swartbooi says workers are paid “peanuts.”

“One of the challenges we are facing here is lack of proper compensation,” he said. “We do a lot of work and it is tough. We take leaves off [the vines], we tie the grapes, hang them out, count them, pack them for export and so on. We start work at 7:30 in the morning work until 5 pm. For that we are paid Namibian N$2,800 – about US$190 – at the end of the month.”

That salary barely buys enough food for a family to last a whole month. In fact, the local Spar supermarket is run by the son of one of the farm owners, which means that a significant portion of the meager salaries of the workers are going right back to the employer.

The settlement also has a small government clinic with only three nurses, a primary school and a shopping center where farmworkers have access to basic services, including banking facilities, a cash loan operation and alcohol. But with their paltry salaries, they can hardly afford to take advantage of many of these services — let alone pay for medical aid, retirement benefits or social security.

Kevin Liddle of Silverlands Vineyards did not answer queries about the worker’s low salaries.

Levi Shimbilingwa has planted a number of aloe vera trees in front of his home. Despite the challenges he faces, Shimbilingwa says that he finds joy in nurturing his plants. Photo: Brandon van Wyk

Living with an ever-present danger of fires

But the problems of the settlement become even more dire when fires break out, a not infrequent occurrence that happens, on average, once every two months. The farmworkers’ homes, often built from reeds, are highly flammable. Once a fire has taken hold of one home, it spreads rapidly to neighboring ones. According to the farmworkers, the main causes are discarded cigarettes and candles.

Dominic Rooy, a 28-year-old farmworker, says when a fire breaks out,“Our only solution is to break down other houses and let one burn, because there is no water to extinguish the [flames].”

Given the health and safety risks, several workers on the vineyards want to quit their jobs. Maria Ipinge, 54, says she is among them, even though she is still six years from retirement age. Ipinge has been a farmworker since December 1999.

“I have been working here for such a long time, and I have been living in these reed houses that look like they are falling apart,” she said. “There is no decent shelter here. I am retiring next year because of the water problem.

“Sometimes water comes, sometimes it doesn’t come at all. But when it comes, it’s only once a week,” Ipinge said.

A tanker carrying purified water. Residents say that water is delivered irregularly and there is not enough for everyone in the settlement. Photo: Brandon van Wyk

Once the delivered supplies of water are finished, residents can also turn to a small reservoir, which is topped up with water pumped from the river, for an alternative source of the much-needed supply. But this comes with challenges, according to Ipinge, “There [in the reservoir] you find hair, used toilet paper and plastics. You can’t really be disgusted because that’s the only water you have,” she said.

Martin Murondo, 28, says that the limited water from the tiny reservoir is a breeding place for algae that starts to grow shortly after they fill buckets from the pipes leading from a man-made zinc dam. As a result, workers who rely on the water for drinking purposes and their children develop diarrheal diseases and stomach ailments.

“The water we are given comes from the river,” Murondo said. “It looks clean, but once you leave it in the bucket or a container for an hour or so, then you will notice green dirt gathering at the bottom. There is better water at the clinic and by the post office, but not in our settlement.”

The story doesn’t end there.

One farmworker, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that farm owners victimize employees who speak out about their appalling living and working conditions:

“Sometime last year I called in to a radio show and spoke about working conditions and saying that all of us want assistance. The complaint was based on working hours. We were told to start working at 4 am, but when working hours are counted, they base it from 7:30 am. I was questioning why it was that way. Since then, I was cut out from working. I haven’t worked ever since.”

The farm owners refused to respond to this specific allegation. However, responding to questions about the workers’ overall deplorable living conditions, the Namibian Grape Growers Association said it is not content with the living conditions of the employees in the informal settlement in Aussenkehr.

The association has acknowledged that the process to improve the workers’ condition has taken longer than they expected. They say that the association is waiting for the government to complete basic infrastructure improvements first, but acknowledge help is already on the way.

“There are a number of projects that the growers are actively pursuing to improve the conditions. These include the construction of over 50 houses, addressing the drinking water challenges (over N$2.5 million already spent by commercial Farmers and more planned) and the provision of support for the local government clinic and police station.”

Some of the burnt houses belonging to farm workers of the Aussenkehr vineyards. They say that there is not enough water for basic needs, let alone to extinguish fires. Photo: Brandon van Wyk

When water becomes deadly

Help cannot come too soon. The lack of access to water has led to several deaths of farmworkers who have drowned in the river over the years. Since 2006, the Aussenkehr police station has recorded 15 deaths of farmworkers who have drowned while swimming, fishing and accessing drinking water.

This includes an incident where four young girls drowned in December 2018, and another where a young boy died in the river May of this year.

The station’s sergeant, Bronwin Appolus, said that he could only provide statistics to the media and not names to protect the deceased’s families.

Regional commander in the Karas Region, Commissioner David Indongo, said he has, on numerous occasions, advised the community not to go to the river due to the increased number of people drowning.

“Many that have drowned are not necessarily due to water access,” Indongo said. “Those ones go fetch water and go back to their homes. But those that go with the intention of crossing the river to go over to the South African side for firewood, for drugs and for alcohol are mostly the ones that drowned.”

Most farm workers interviewed disputed Indongo’s statements, saying they do not participate in illegal activities. They said the deaths occur when they drown trying to access water for cooking and cleaning, as well as when fishing.

New hope or false dawn?

Comprised almost entirely of hyper-arid, arid and semi-arid land, Namibia receives the least rainfall in southern Africa. This is made worse by recurring droughts and unpredictable rainfall due to climate change, which emphasizes the reality of water scarcity in the country. As such, the Namibian government declared three states of emergency between 2013 and 2019 related to drought, with 2019 being the driest year in 90 years.

The reed houses where Aussenkehr farm workers live. The houses have no toilets or electricity. Photo: Brandon van Wyk

Promises, promises, promises…

This drought has exacerbated the plight of the grape farmer workers, whose lack of water and poor living conditions has been like this for many years.

The Minister of Agriculture, Water and Land Reform, Calle Schlettwein, said plans are finally afoot to restore the the farmworkers’ dignity:

“The industry together with the government has embarked on the development of a formal settlement. The grape industry supplied the required land, and all 990 erven [plots of land] have been fully serviced. Clean water will be supplied by NamWater from the recently commissioned treatment plant, and NamPower has connected the settlement to the power grid.”