California Tribes Call Out Degradation of Clear Lake

A monitoring program tracks toxic cyanobacteria and influences change

A monitoring program tracks toxic cyanobacteria and influences change

Formed some 2 million years ago at the intersection of three geologic faults, Clear Lake is a natural marvel, considered the oldest lake in North America. It is also the site of severe blooms of toxic cyanobacteria from June through November that obscure the water and are a risk to health and safety. Photo © Brett Walton/Circle of Blue

This piece is part of a collaboration that includes the Institute for Nonprofit News, California Health Report, Center for Collaborative Investigative Journalism, Circle of Blue, Columbia Insight, Ensia, High Country News, New Mexico In Depth and SJV Water. It was made possible by a grant from The Water Desk, with support from Ensia and INN’s Amplify News Project.

Key Takeaways

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue — May 3, 2021

[bctt tweet=”Over the last century and a half, the ecological balance of California’s Clear Lake has become undone, and 85 percent of the lake’s nutrient-absorbing wetlands have been destroyed. #TappedOut ” username=”circleofblue”]

LAKEPORT, California — Seven years ago, after the fish died, Sarah Ryan decided she couldn’t wait any longer for help.

California at the time was in the depths of its worst drought in the last millennium and its ecosystems were gasping. For Ryan, the fish kill in Clear Lake, the state’s second largest and the centerpiece of Lake County, was the last straw.

Ryan is the environmental director for Big Valley Rancheria, a territory of the Big Valley Band of Pomo Indians that sits on the ancient lake’s western shore. She and others raised alarms for several years about increasingly dire blooms of toxic cyanobacteria. But Lake County officials and state agencies were not gathering the data on toxin levels that Ryan thought was necessary to adequately communicate the health risks to tribe members or to anyone else using Clear Lake to swim, fish, drink — or walk their dog.

A year earlier a dog had died after drinking lake water. Fishing tournaments were cancelled due to the noxious scum, and the lake was starting to smell rotten in the warm months. It was time to act, she thought.

Along with Karola Kennedy, then the environmental director at Elem Indian Colony, another area tribe, Ryan developed a plan. In the summer of 2014 Ryan and Kennedy laid out a map on a table — “our war room,” as Ryan described it — and chose several shoreline sites to collect water samples. They sent the samples to the lab and waited.

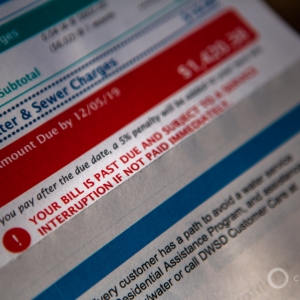

The first results came back in early September, well after midnight on a Friday. Ryan was still awake. She looked at the readout on her screen. A sample taken about 100 feet from a drinking water intake showed more than 17,000 micrograms per liter of microcystins, a liver toxin produced by the microcystis species of cyanobacteria. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency health guideline for microcystins in waters where people swim and boat is 8 micrograms per liter. California suggests posting warnings at beaches when levels reach 0.8 micrograms per liter.

“Oh my gosh,” Ryan recalled thinking. “We have a problem here.”

The sample results, and the work Ryan and Kennedy have done to promote and explain the implications for public health and the recreational economy, prompted local and state responses that distinguish Clear Lake as a test bed for understanding and solving a worsening global water pollution challenge.

Neither California nor the federal government regulate cyanotoxins in drinking water. Two-thirds of Lake County’s 65,000 residents are served by utilities that use Clear Lake as a water source. What government officials want is more data. Starting this summer, the State Water Resources Control Board ordered the 18 public water systems that draw from Clear Lake to test their treated and untreated water every two weeks for microcystins. In addition, the Water Board asked the state Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment in February to evaluate scientific information on four cyanotoxins and recommend whether the state should establish notification levels, which are health-based thresholds that require utilities to tell customers when the toxins are present.

Sometimes called blue-green algae and a constituent of harmful algal blooms, cyanobacteria are single-celled organisms that turn sunlight into energy. Alive on the planet for more than 2 billion years, they were the first species to produce oxygen as a by-product of respiration. You and I can be thankful for that. But because they’ve endured the eons — outlasting ice ages as well as hothouse conditions — they are adaptable survivors.

“In a way, their playbook is very deep,” Hans Paerl, a professor at the UNC Chapel Hill Institute of Marine Sciences and one of the country’s foremost researchers of cyanobacteria, told Circle of Blue. “Evolution has served them for a long period of time.”

Today, however, a deep playbook is less and less necessary. Humans are making it easier on cyanobacteria. The organisms live everywhere, but they prefer warm, stagnant waters that are saturated with nutrients. As they see it, a planet blanketed by heat-trapping greenhouse gases, loaded with nitrogen and phosphorus, and saturated with slack water and rivers impeded by dams is a cozy and welcoming home.

“Almost every modification we’ve gone through — in terms of creating more nutrients or altering the flow of water in natural systems — seems to benefit their ability to form blooms and proliferate in those blooms,” Paerl explained. The blooms, in other words, are living in a boom time.

Clear Lake, about 100 miles north of San Francisco, is relatively shallow, warm and, by its nature, biologically productive. That’s why it’s known as one of the best bass fishing spots in the country. It’s also considered the oldest lake in North America, which means that algae have probably been present for some portion of its 2 million years. Indigenous groups have lived along the lake’s clean waters and fertile shores for some 12,000 years.

But over the last century and a half, Clear Lake’s ecological balance has come undone. White settlers planted orchards, dug mercury mines, and built homes and towns. In the process an estimated 85 percent of the lake’s nutrient-absorbing wetlands were destroyed.

Unimpeded flows of nitrogen and phosphorus tipped Clear Lake into hyperproductivity, or eutrophication. Algae and cyanobacteria blooms worsened in the 1970s, starting improving through the 1990s, and now are as extensive as any in generations. While the middle of the lake can be scum-free, the blooms paint the nearshore waters in the summer and fall in whorls of green and white. They emit terrible odors, described by various locals as like kimchi, dog poop, baby’s diaper, sewage, and “not as pungent as skunk, but on its way there.”

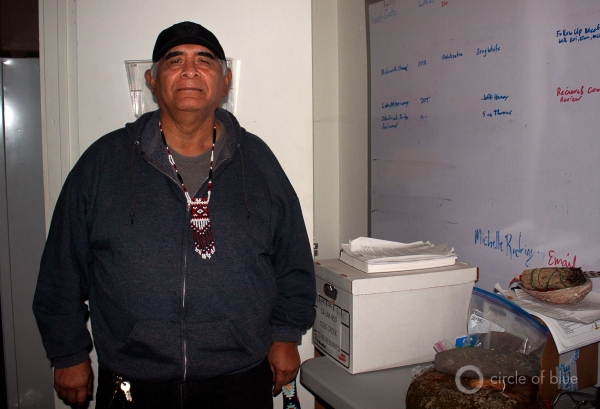

An elder of the Big Valley Band of Pomo Indians, Ron Montez, Sr. has spent a lifetime around Clear Lake. The lake is central to the tribe’s culture, he said while at his office. Members collect tule reeds around its shores for making baskets and canoes and they immerse themselves in the water before dances and ceremonies. Photo Brett Walton/Circle of Blue

[bctt tweet=”“The water is very important. It’s tied to us spiritually, physically. That has all been reduced because of the algae and other contaminants out there.” – Ron Montez Sr., an elder of the Big Valley Band of Pomo Indians. ” username=”circleofblue”]

Ron Montez Sr., an elder of the Big Valley Band of Pomo Indians, has witnessed those changes. He grew up around the lake, but his family had no running water. Instead they used buckets to gather from the lake what they needed at home. If algae were present, they would filter the water by pouring it through a cloth. To bathe, he would jump in the lake. Sometimes he would hold bread in his hands until the fish nibbled.

Montez, who is 71, told Circle of Blue that the lake is central to his cultural identity and for his community’s livelihood. It’s where they collect tule reeds for weaving baskets and making boats, where they caught catfish, hitch, and perch for sustenance and income, where they splished and splashed. The lake is also where tribe members congregate for ceremonies, like the annual Big Head dances held in the spring.

“Before any dance we have to enter into the water, have our heads under the water,” Montez explained. The tribe members dance also for healing if someone is sick. “It’s cleansing before that time [of the dance], which is sacred.”

Montez continued. “The water is very important,” he said. “It’s tied to us spiritually, physically. That has all been reduced because of the algae and other contaminants out there.”

The environmental director for the Big Valley Band of Pomo Indians since 2006, Sarah Ryan has been instrumental in bringing attention to the harmful algal blooms and toxic cyanobacteria that blanket the shores of Clear Lake in the warm months. Photo © Brett Walton/Circle of Blue

Sarah Ryan is not indigenous, but she has worked for Big Valley’s environmental department since 2001, becoming director in 2006. She notes that tribal governments in California, especially those along the Klamath River, have taken the lead on responding to toxic cyanobacteria.

Ryan said the initial goal of the cyanobacteria monitoring program was to protect the health of Montez and other Big Valley Band members as they took part in the traditional cultural practices. The program costs Big Valley about $70,000 a year to operate for staff time, sample analysis, and equipment, Ryan estimates. Two or three Big Valley EPA staff members collaborate on the field work, sample collection, data entry, and public outreach. The funds come from state and federal grants, and they’re needed. Clear Lake has 100 miles of shoreline.

Monitoring sites were selected because of their importance to the tribes. Sampling more than 20 sites every two weeks in the summer and monthly in the winter is not a simple task. Ryan expects to be particularly active this year. The lake is at its lowest level since 2014, and the state is coming off its third-driest winter on record. In these conditions, blooms are likely to be very bad, she said.

Around Clear Lake the influence of the monitoring program keeps growing. The data informs warning signs that the county posts at parks and boat launches. Ryan tallies the results on the Big Valley website, too. There have been follow-on studies of toxins in fish tissue and in private drinking water intakes. Public drinking water providers check the data for toxin levels around their intakes.

The monitoring program aligns with Ryan’s world view. Her father worked for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and she got her bachelor’s degree in government from the College of William and Mary. Science on one hand and policy on the other. Her mission is to ensure that the two stay connected.

“Government should be translating science into actionable items,” she said. “Otherwise, what are you doing?”

Though poisonings from drinking water are rare, simply being at the lakeshore when blooms are present is a risk. Touching certain cyanotoxins can cause rashes and allergic reactions. That’s why the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency published its guidelines for recreational water. It’s also why the tribes wanted more information about what their members might be exposed to during their ceremonies.

Health hazards do not end with skin contact. In a peer-reviewed study published in April, researchers found that a harmful algal bloom on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts, was releasing anatoxin-a, a neurotoxin, into the air. The researchers speculate that sharp winds sent the toxin airborne, but it is unclear what effect inhaled toxins might have on human health.

The risk of aerosolized toxins is high enough that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention will begin a study this year to assess airborne exposure in Florida residents who live or work on Lake Okeechobee, St. Lucie River, Caloosahatchee River, and Cape Coral canals — all places with a recent history of severe blooms. Results are expected in 2023.

Though most attention is directed at phosphorus, Paerl says that nitrogen should not be neglected, either. Nitrogen is more manageable, Paerl told Circle of Blue. It can be cut more easily by restricting polluted runoff from streets, farm fields, septic systems, and wastewater treatment plants, while also minimizing erosion. Paerl has studied harmful algal blooms in large lakes worldwide, from Lake Erie to Lake Taihu, in China.

“That’s one thing we are prescribing for many of the large lakes that Clear Lake fits into: not only to reduce phosphorus inputs because it takes so long for the system to clear itself of phosphorus,” Paerl said. “But also deal with nitrogen.”

There is an official process in this country for these nutrient diets. It’s called a total maximum daily load, or TMDL. Written into the federal Clean Water Act, TMDLs are a regulatory tool for reducing pollution in a waterbody. Some TMDLs apply to stream segments of fewer than a dozen miles; others, like the one for the Chesapeake Bay, encompass entire watersheds.

Clear Lake has a nutrient TMDL that was put in place in 2007, but for phosphorus only. It identifies forest roads, county and federal lands, and irrigated agriculture as primary sources of sediment erosion.

Nearly a decade ago, Ryan warned state officials that the TMDL was not effective.

“It is obvious that the measures being taken by the communities in the Clear Lake Basin are not reducing nuisance algal blooms,” Ryan wrote to the State Water Resources Control Board on August 20, 2012.

Karola Kennedy, her partner in developing the cyanobacteria program, also notified the Water Board of concerns about the TMDL. She said that projects to control erosion were not being monitored to assess whether they lived up to their promises. Kennedy did not want the state to extend compliance dates for reducing nutrient flows, which it is still considering.

“The Elem Indian Colony Tribal community does not want to wait another generation for compliance on the nutrient TMDL,” Kennedy wrote on October 3, 2017. “Water quality issues have exponentially worsened in the past decade. We are fearful of what is to come if the responsible parties are given a pass for another generation.”

Kennedy, now the water resources manager for Robinson Rancheria, another Clear Lake tribe, told Circle of Blue that the lack of monitoring for erosion control is still a problem today. “It’s hard to say if those best management practices are truly that. If you don’t monitor them, you can’t manage it.”

The Central Valley Regional Water Quality Control Board is the state agency that oversees the TMDL. Adam Laputz, the board’s assistant executive officer, told Circle of Blue that the board is reviewing the TMDL to see if it should be extended or revised. Laputz said that any revisions would take into account new research in the last 15 years on the causes of harmful algal blooms and could include nitrogen limits or changes to the amount of phosphorus allowed into the lake. But given all the factors that feed the blooms — nutrients, water temperature, wind and water currents — determining whether the TMDL has been effective “is a very difficult question to answer,” Laputz said.

One major project that aims to prevent more nutrient-laden sediments from flowing into the lake and to reverse the loss of wetlands is the restoration of a marsh ecosystem downstream of Middle Creek and Scotts Creek. Located at the northern end of the lake, the site contributes about 70 percent of the sediment and phosphorus that flow into the lake. By one estimate, restoring 1,400 acres of marsh where there are now fields and levees could increase the lake’s wetland coverage by 70 percent and reduce phosphorus inputs for the lake’s upper basin by 28 percent. Those reductions are only on paper right now. The county is still acquiring land for the project and has not started construction.

The Middle Creek restoration is an important step, but larger schemes could be on the horizon. In 2017, an act of the Legislature established a 15-member Blue Ribbon Committee to discuss the restoration of Clear Lake. The act also funded an in-depth research program that is being led by the University of California, Davis. The goal of the program is to observe how water and nutrients move throughout the watershed.

The California Natural Resources Agency said it is working on a grant that will extend funding for the program, which needs more data before it can fine-tune a working model of the watershed and lake dynamics. According to Geoff Schladow, the research program’s principal investigator, the model will provide glimpses of the future. Once the model is running, researchers can tweak variables like nutrient inputs, wind speed, and air temperature to test their effect on the blooms, which tend to concentrate in two of the lake’s sub-basins, the Oaks Arm and Lower Arm. That way, local agencies could issue cyanobacteria forecasts, directing swimmers and boaters away from hazardous areas and warning tourists coming up from San Francisco for the weekend about which beaches to avoid. The tribes, though, cannot simply change the location of their ceremonies.

One theory is that blooms proliferate in the Oaks and Lower arms because the lake is deeper there and phosphorus in the lakebed sediment becomes unbound when oxygen is depleted. This “internal loading,” a legacy of centuries of erosion, is actually the largest source of phosphorus available to fuel cyanobacteria growth in the lake. Schladow said a potential remedy is to inject oxygen in these areas when levels reach critical thresholds. But researchers won’t know whether that’s the case until their model is complete and they can run tests. The results matter not just for scientific discovery but also for fiscal responsibility.

“The truth of the matter is lake remediation costs a lot of money and you can’t afford to get it wrong,” Schladow told Circle of Blue.

Angela De Palma-Dow, the invasive species coordinator for the Lake County Water Resources Department, reiterated that point. Lake County is one of the poorest in California, and there is not a lot of spare cash to throw at false solutions.

“It’s hard for us to put money into a project and have it have a negligible impact on water quality,” De Palma-Dow told Circle of Blue. She hopes the UC Davis study will provide recommendations that are “targeted and relevant.”

Researchers who study Clear Lake are full of praise for the program that Ryan and Kennedy started. It’s hard to imagine so much legislative and scientific attention directed at the lake if not for the work of the tribal governments.

“The fact they’ve been collecting data has raised the awareness in the whole community,” Schladow said. “We would be a long way further back if it wasn’t for those efforts.”

Local officials acknowledge that the tribes are providing a public service that they are not able to fulfill.

“Frankly, there’s no way our county would be able to do that work and we rely heavily on them and what they do,” De Palma-Dow said. “They’re great partners.”

Ryan said that it took many years of cajoling before those partnerships took root and bore fruit. She’ll keep pushing colleagues in county and state agencies, because after all, science without government action to back it up is just not enough.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Universal WASH Gains Traction Even as Hand Pumps Lose Ground

Universal WASH Gains Traction Even as Hand Pumps Lose Ground