Years After Flint Water Crisis, Lead Lingers in School Buildings Across the Nation

In its 2021 budget, Congress included millions for lead testing in schools, where children are still exposed to the toxic metal.

Community organizers in Flint, Michigan utilize a closed elementary school to distribute bottled water after the Flint water crisis. Photo: 2016 Photo © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Jane Johnston, Circle of Blue

The federal appropriations bill for the 2021 fiscal year, signed into law this week, included $26.5 million to test for lead in schools and child care centers, a nod to the legacy of the Flint water crisis, which lifted the issue of lead in drinking water into the national spotlight.

The bill was signed a week after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency introduced new requirements for water utilities to test water in elementary schools and day cares for lead.

The Flint crisis spurred a national conversation on the dangers of exposing children to lead. “It really alters the entire life-course trajectory of a child,” Mona Hanna-Attisha, a Flint pediatrician, told Circle of Blue. Hanna-Attisha’s research helped uncover the extent of the city’s lead contamination, revealing elevated lead levels in the blood of children who ingested improperly treated water supplied from the Flint River.

Flint’s water is now being mended and its lead pipes are nearly all replaced. But the toxic metal still lingers elsewhere. A 2019 report from Environment America, a national network of environmental groups, showed elevated lead levels in the water systems of schools across the country.

John Rumpler, Environment America’s clean water program director, told Circle of Blue last summer that schools need more attention because of potential harm to the brains of young children.

“There’s no safe level of lead, according to most health authorities,” Rumpler said. “We know that even at low levels, lead can have really serious impacts on the way our kids think, learn, behave and develop.”

As of 2018, only half of states required that schools test their water supply for lead. A survey conducted the Government Accountability Office, a watchdog agency, found that only 43 percent of school districts had tested their water for lead in 2017. School districts that did test often reported contamination. Rumpler said that’s not surprising.

Even after lead pipes were officially outlawed in 1986, brass fixtures were allowed to carry some amounts of lead until 2014. “I would say there is a strong likelihood that there is lead contamination, or at least a clear risk of lead contamination for all schools that were built before 2014,” Rumpler said.

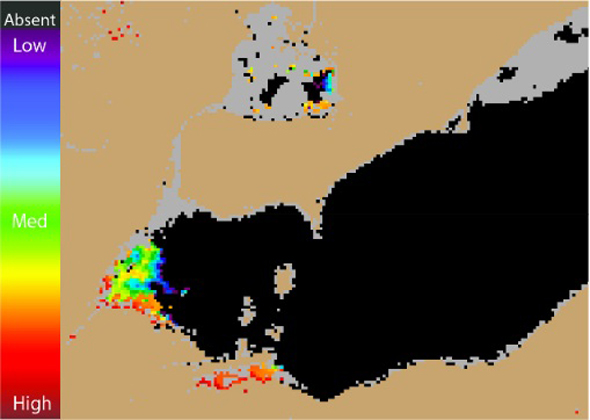

Rather than being concentrated in large cities, lead in water is an extensive problem. In California, the state legislature passed a law in 2017 mandating that schools test portions of their water supply for lead. After the testing deadline had passed, the non-profit California Public Interest Research Groups assembled an interactive map with data from all reporting schools.

The map indicates that 53 percent of all reporting schools in California across rural, urban and suburban areas have lead in their water. For children in low-income schools or low-income areas, Hanna-Attisha said exposure to lead in water can be more widespread and less likely to be quickly remediated, or in many cases, even acknowledged.

“The burden, like most public health injustices, does not fall equally on our nation’s children,” she said. “Kids who already have all these other adversities and toxicities to life have higher lead exposures to start with, so there’s this unfair burden that widens other inequities.”

The EPA’s new rule is intended to provide more information about lead contamination. The rule requires water utilities to test drinking water in 20 percent of elementary and childcare facilities in their service area each year. Over five years, all such facilities will be tested, but there are limits to the rule’s effectiveness, said Elin Betanzo, founder of the consulting firm Safe Water Engineering.

Betanzo said that the rule is significantly more complex than current requirements. It forces utilities to develop new relationships and expand their testing programs. New data will be generated but the rule does not require the provision of safe water to schools.

“There’s no action to reduce lead exposure in schools,” said Betanzo, a former EPA staff member who helped to uncover the Flint water crisis. Schools are not likely to have lead service lines, she said, so any contamination in those buildings would result from plumbing components like solder and fixtures.

The fight for lead-free drinking water will likely go on for decades to come. Removing lead pipes can be expensive, although some research has found that removing leaded water service lines could save billions in the long run. The challenge is persuading governments to fund the solutions in the short term.

Rumpler said he’s excited to see more state and federal interest in remediating lead service lines, but there’s much more work to do.

“I don’t think I’ll ever say enough is being done until all lead service lines are removed and we’ve replaced the faucets and fountains at schools around the country with truly lead free materials and put (lead-removing) filters on,” he said.

This article was updated for clarification on Jan. 23.

Jane is a Communications Associate for Circle of Blue. She writes The Stream and has covered domestic and international water issues for Circle of Blue. She is a recent graduate of Grand Valley State University, where she studied Multimedia Journalism and Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies. During her time at Grand Valley, she was the host of the Community Service Learning Center podcast Be the Change. Currently based in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Jane enjoys listening to music, reading and spending time outdoors.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!