CAPE TOWN — With her 18-month-old daughter suffering from acute diarrhea in mid-February, Novangele Nyikana left the one-room home she shares with her partner and children, and sought help at the Khayelitsha hospital in Cape Town.

Nyikana’s daughter Thina was admitted and spent three weeks being treated for what is the second leading cause of death among young children globally. In Cape Town, 20 children have died due to diarrhea this summer thus far, according to city and provincial government spokespersons, Luthando Tyhalibongo and Mark van der Heever, respectively.

Khayelitsha hospital does not have beds for patient attendants to sleep on. Nyikana spent her nights trying to sleep in a chair and got a kidney infection after a week for which she was treated with intravenous antibiotics for seven days. After recovering, she spent another week on the hospital chairs.

Back home in the Taiwan informal settlement of the sprawling and densely populated Khayetlitsa township, her partner, Sicelo Kupe, cared for their three other children. This meant neither Kupe or Nyikana, who are both unemployed, could look for work opportunities to supplement the meager income they receive from two child support grants.

Sicelo Kupe walks his eldest daughter, Sonele home from school along streets polluted by sewage spilling from broken infrastructure in Site C, Khayelitsha, Cape Town.

Less than a month after the youngest came out of the hospital, Nyikana’s two-year-old got diarrhea, too. Having lost her appetite, the limp toddler displayed none of the energy expected at that age when this reporter visited their home in early April.

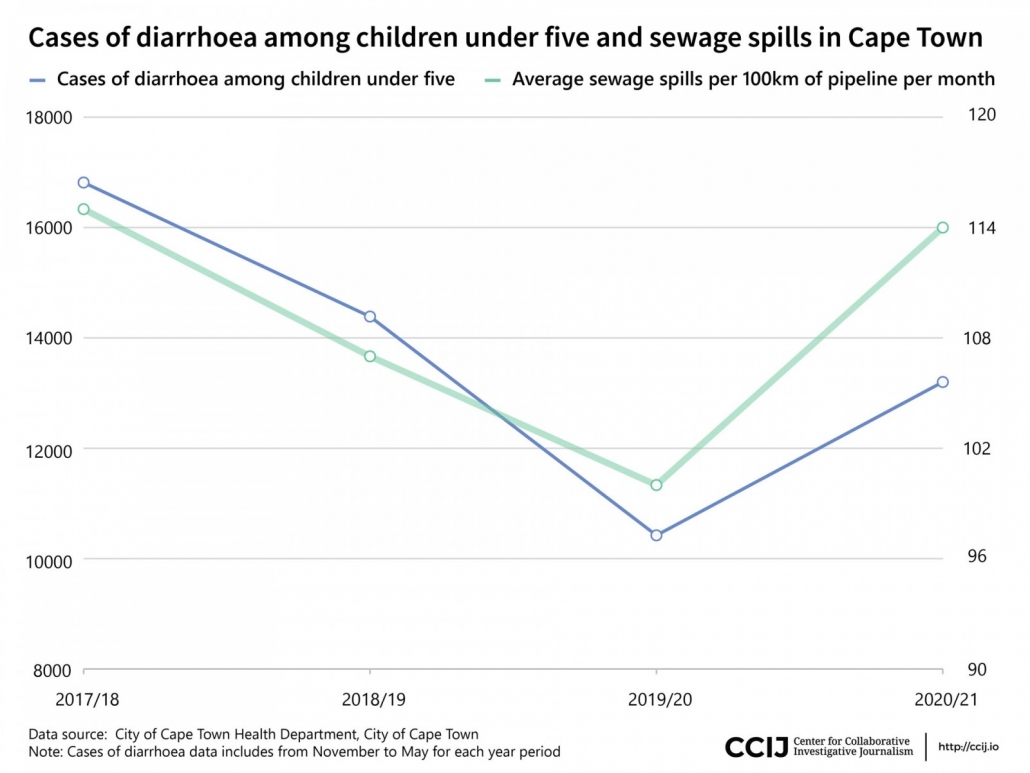

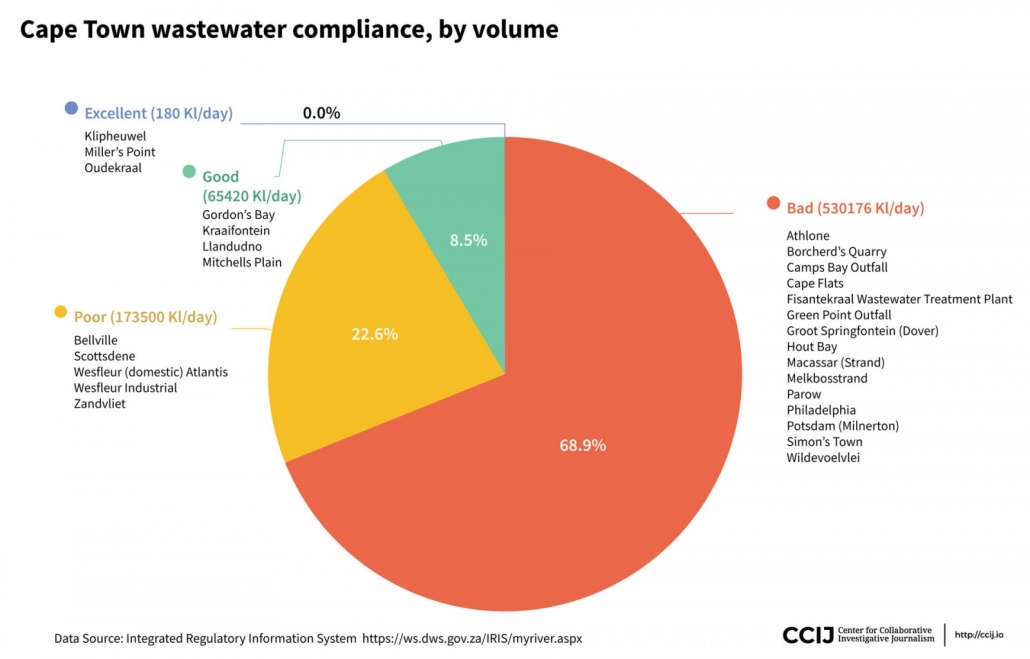

There is no running water in their home but sewage runs along the streets. Water is collected from a communal standpipe about 30 meters away and the family has to use a communal toilet. There are five toilets for an estimated 100 families in their section of the settlement. But arguably the largest threat to the children’s health is the raw running sewage.

There is hardly a street in the area that does not have broken and overflowing sewer covers. Almost every journey – all taken on foot – involves stepping through or across puddles or potholes contaminated with sewage. This includes the walk Nyikana’s preschooler takes to kindergarten. Living in the close confinement of one room, it is almost impossible to prevent this contamination being traipsed into the home. It is not surprising then, that Nyikana’s children are among the thousands treated for diarrhea in the past six months.

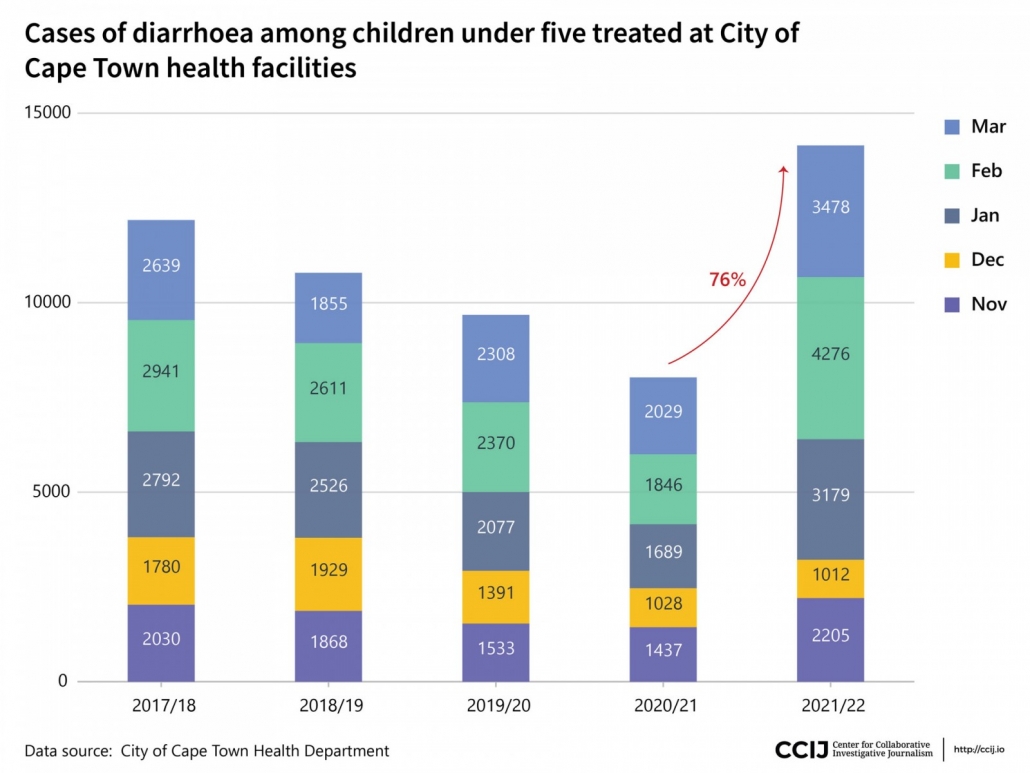

According to Patricia van der Ross, a member of the city’s mayoral committee for health, day clinics run by Cape Town city authorities treated 4,533 infants for diarrhea during February, a 146% increase from February 2021. Hospitals, such as the Khayelitsha Hospital where Nyikana’s 18-month-old child was treated, and which are managed by the provincial government, treated an additional 4,024 cases between November and the end of April this year. This summer (November through April in the southern hemisphere), a total number of 18,174 cases were reported across Cape Town.

Cape Town’s long summer is known as the “surge season.” Every year, diarrhea cases among children rise dramatically from single digits in October, to about 2,000 in November, dropping off equally dramatically in June.

With still a month to go in the current surge season, city health clinics have reported 14 child deaths due to diarrhea, while six children have died from the same cause at provincial hospitals within the city.

Novangele Nyikana holds her baby daughter, who spent three weeks in hospital with diarrhoea, while her partner Sicelo Kupe holds their two-year-old daughter outside their home in Taiwan, an informal settlement in Khayelitsha, Cape Town.

Sewage spills across the street leading to the Nolungile health clinic in Site C, Khayelitsha in Cape Town, where mothers living in the area take their young children to be treated for diarrhoea.