By, Pablo Unzueta

A dead bird lies on the slanted pavement, its neck twisted in the shape of an ‘S’. In the distance, a lone man makes his way across a slippery concrete riverbed, now coated in algae. Occasionally, a piece of trash floats downstream, slowly advancing toward the Pacific. A pair of Canada geese pick through the trash, looking for food. On both sides, the riverbed is guarded by a steep, slanted slope.

This is the tail end of the Los Angeles River, a waterway at risk.

From its source in the Santa Susana Mountains to its union with the sea at Long Beach, the river snakes through 17 different cities in a journey of just 51 miles. But even within that short course, there are perils.

Today, the L.A. River is at a pivot point. Development, pollution, and poor management are significant threats to the river’s health. Earlier this year the environmental group American Rivers ranked the L.A. River as the 9th most endangered river in the country.

In its recent history, the river has been abused by its urban setting, channelized and tainted with industrial runoff. But along its northern reaches, a restoration is taking shape.

The L.A. River Master Plan, which aims to improve the profile of the river over the next 25 years, was approved by Los Angeles County officials in May. The plan seeks to renovate around river-adjacent communities that have historically been harmed by racial, environmental, and institutional injustices. These communities are also some of Southern California’s poorest and most polluted.

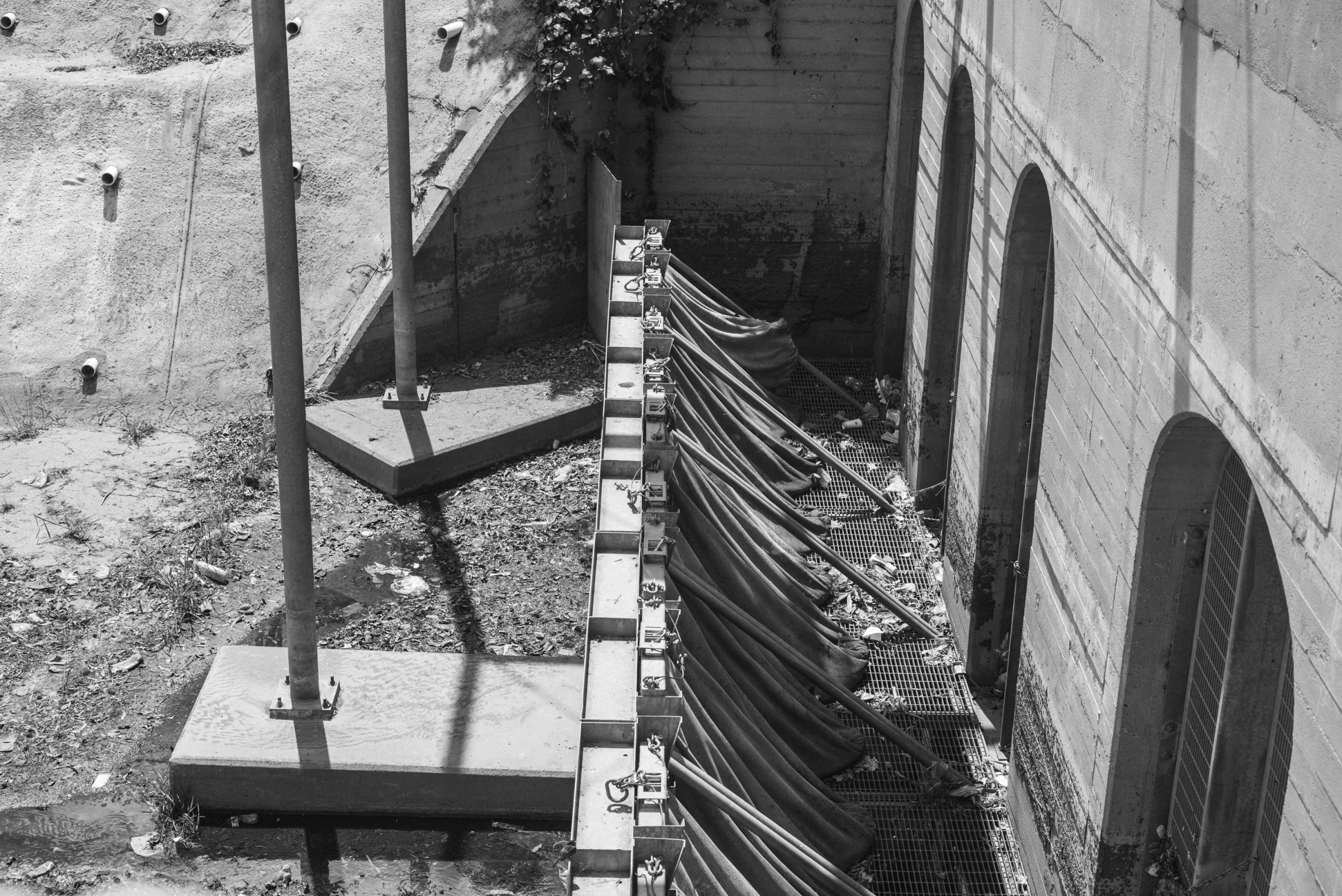

Environmentalists, however, have voiced their concern over certain elements in the Master Plan. In addition to reservations about how water recycling goals will be implemented, they object to expanded hardscapes. Since the late 1930s, nearly 3.5 million barrels of concrete have transformed the river into a flood control channel. The Master Plan would use more concrete in the vicinity of communities that are already impacted by industrial pollution and climate-related issues such as extreme heat and less rain.

For four months in the spring and summer of 2022, I documented the L.A. River and Angelenos who use the river as characters in the widening and complex story of climate change and how our access to clean water is at a critical and fragile crossroads.

The people who allowed me to document their lives along the L.A. River also illustrate the universal relationship that we share with water.

This is the state of one of Los Angeles’s most prized and historical symbols, an enduring source of life for the region’s environment, culture, and people.

Pablo Unzueta is the recipient of Circle of Blue’s inaugural Water & Climate Fellowship program, supported by Aqualateral.

Although some natural sections remain, the L.A. River is 95 percent concrete, according to American Rivers. Los Angeles County has come up with a new Master Plan for the river that relies on adding more concrete. Local environmentalists say that this tactic does not address climate change. Two of the biggest threats to the health of the river are industrial pollution and over-development, which disproportionately affect marginalized communities and their access to nature.

“It’s beautiful here,” Ricardo said, holding up a pair of rusted coins that he found by the water. Ricardo says he is unhoused and makes his way down to the river every other day to look for coins, or anything of value that flows downstream. “Sometimes I’ll just walk along the water because it’s peaceful.”

A lone person walks along the L.A. River, where trash is scattered on the riverbed. Some of the trash enters through stormwater pipes. Eventually it ends up in the Pacific Ocean. The southern reaches of the L.A. River, through Long Beach, are its most industrialized and polluted.

Trash floats on the L.A. River. Some of it will end up in the Pacific Ocean.

A cyclist rides through the L.A. River and along the I-710 and I-105 freeways. Typically during a rainstorm, stormwater will overflow onto the concrete channel, carrying pollutants such as herbicides, oils, industrial waste, and plastics.

Damon feeds his dogs, Barney and Trouble, after giving them a bath in the L.A. River. Damon has lived in his encampment by the river for 10 years. “Water,” Damon said, explaining why he has lived there for so long. “It’s empty, no one comes here.”

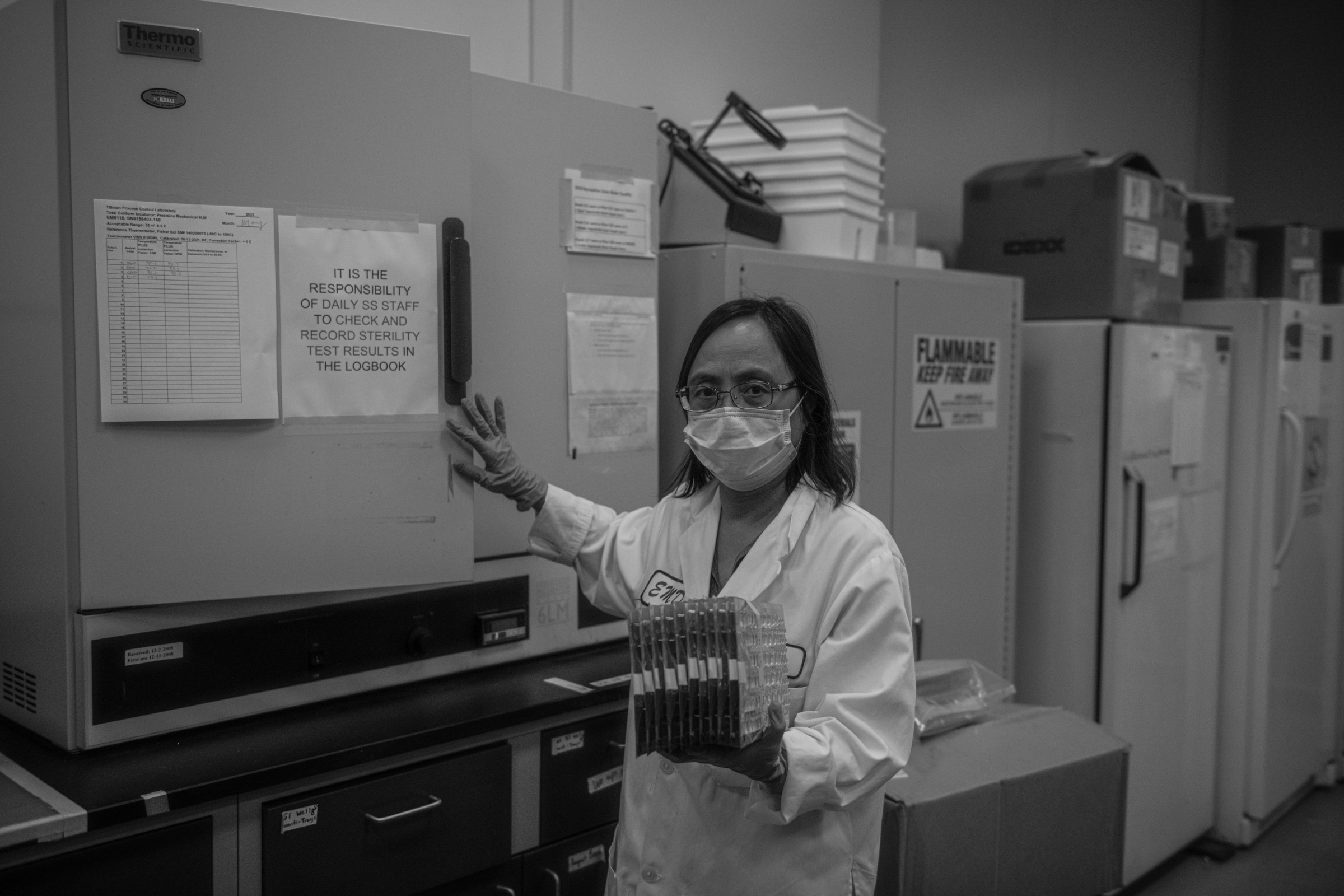

The Donald C. Tillman Plant is designed to treat 80 million gallons of wastewater per day, and 27 million of those gallons go back to the L.A. River, according to Michael Ruiz, a shift superintendent for the Department of Public Works, Bureau of Sanitation. The Tillman Plant is one of the two wastewater plants that supply the L.A. River with water. “There is no river without the plant,” Ruiz said.

A Bureau of Sanitation staff member holds test water samples from the L.A. River inside a laboratory of the Donald C. Tillman Reclamation Plant. The samples are tested twice a week for the presence of E. coli bacteria.

Heavily contaminated water samples collected from the L.A. River. The federal Clean Water Act limits bacteria levels to 235 per 100 milliliters near the Sepulveda Basin and Elysian Valley, the northern stretch of the river, where most recreational access is located. Bacteria levels fluctuate, sometimes spiking in the last five years to more than 20,000 per 100 milliliters.

Roberto gazes into the distance near his home by the L.A. River, where he has lived underneath a bridge for three years. Roberto is also a fisherman and enjoys the freedom of catching common carp, which is also known as “sewer salmon,” a term for fish living in the polluted and muddy waters of the L.A. River.

Roberto cracks open a wild-caught oyster from the Pacific Ocean. According to Roberto, he uses the oyster meat for bait. His line also features a makeshift bobber.

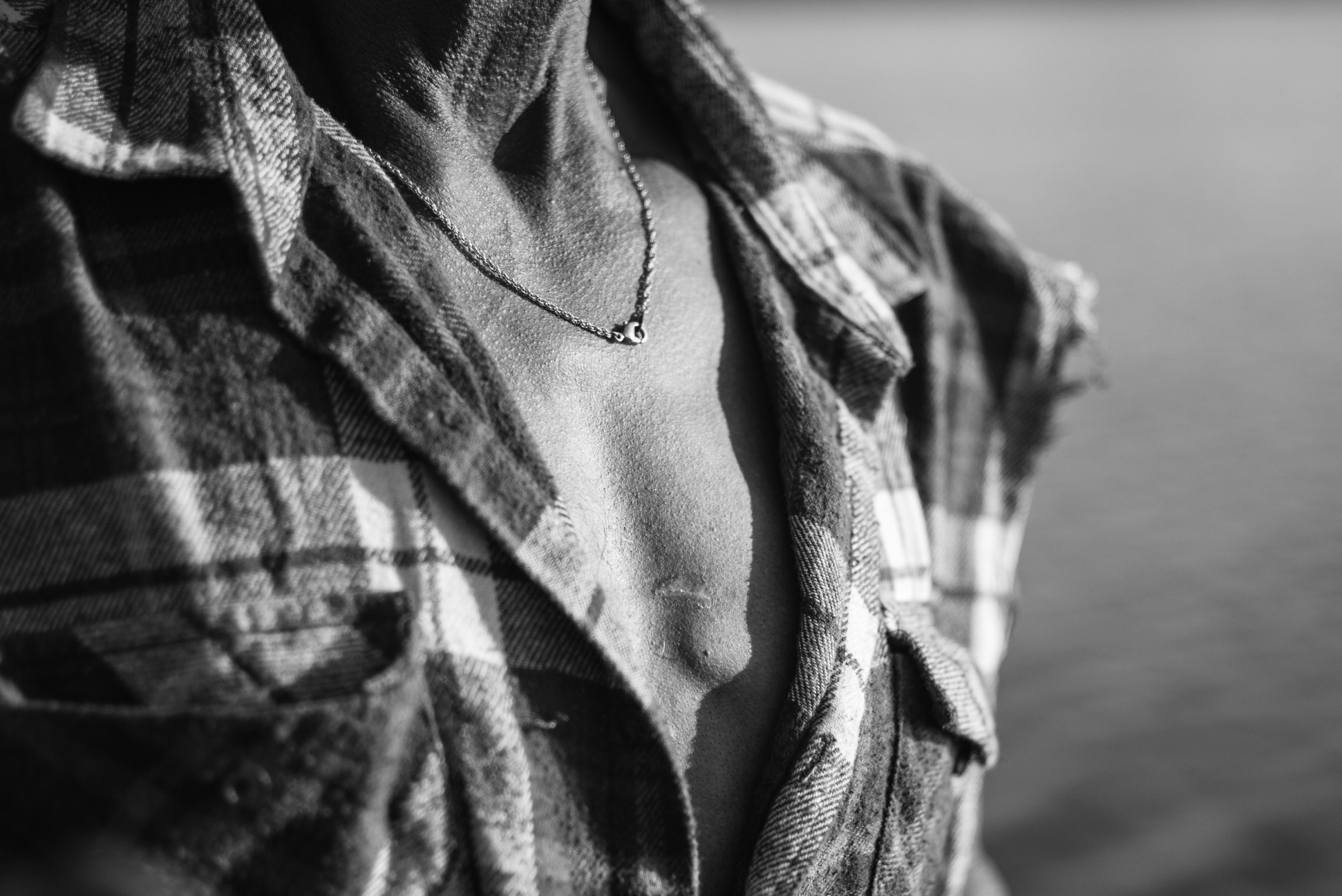

A scar on Roberto’s chest peaks out from his shirt. Roberto says he got the scar after a charred piece of firewood burned him.

When the river is low, Roberto likes to workout close to the water and do push-ups and dips.

Roberto’s shadow covers a painting depicting the Pacific Ocean. Roberto painted this on the wall of the bridge where he lives, near the L.A. River. “I don’t know what it is, but the water can make you feel sadness, or it can make you think about your life,” Roberto said. The entire painting centers around human interaction with water, he explained.

Industrial warehouses and encampments line the L.A. River, along with signs prohibiting illegal dumping, a major issue in L.A. County. Some of the trash ends up in the river, and eventually the Pacific Ocean.

The L.A. River is connected to nearly 2,000 storm drains, which carry industrial runoff and debris.

Active pumpjacks sit between the L.A. River and the I-710 freeway in West Long Beach, the location of many industrial operations. People living in this area have a higher cancer risk than the national average. These facilities can release toxic organic compounds into the air and water.

Missy Clinton, 53, reveals a tattoo on her leg of a dagger inscribed with her son’s name, Cody. Clinton said she got the tattoo when Cody was 9 years old and they were homeless. Clinton now lives along the river with her husband. She reflected on her journey: “It sends me happiness, but it sends me a lot of heartache, too.”

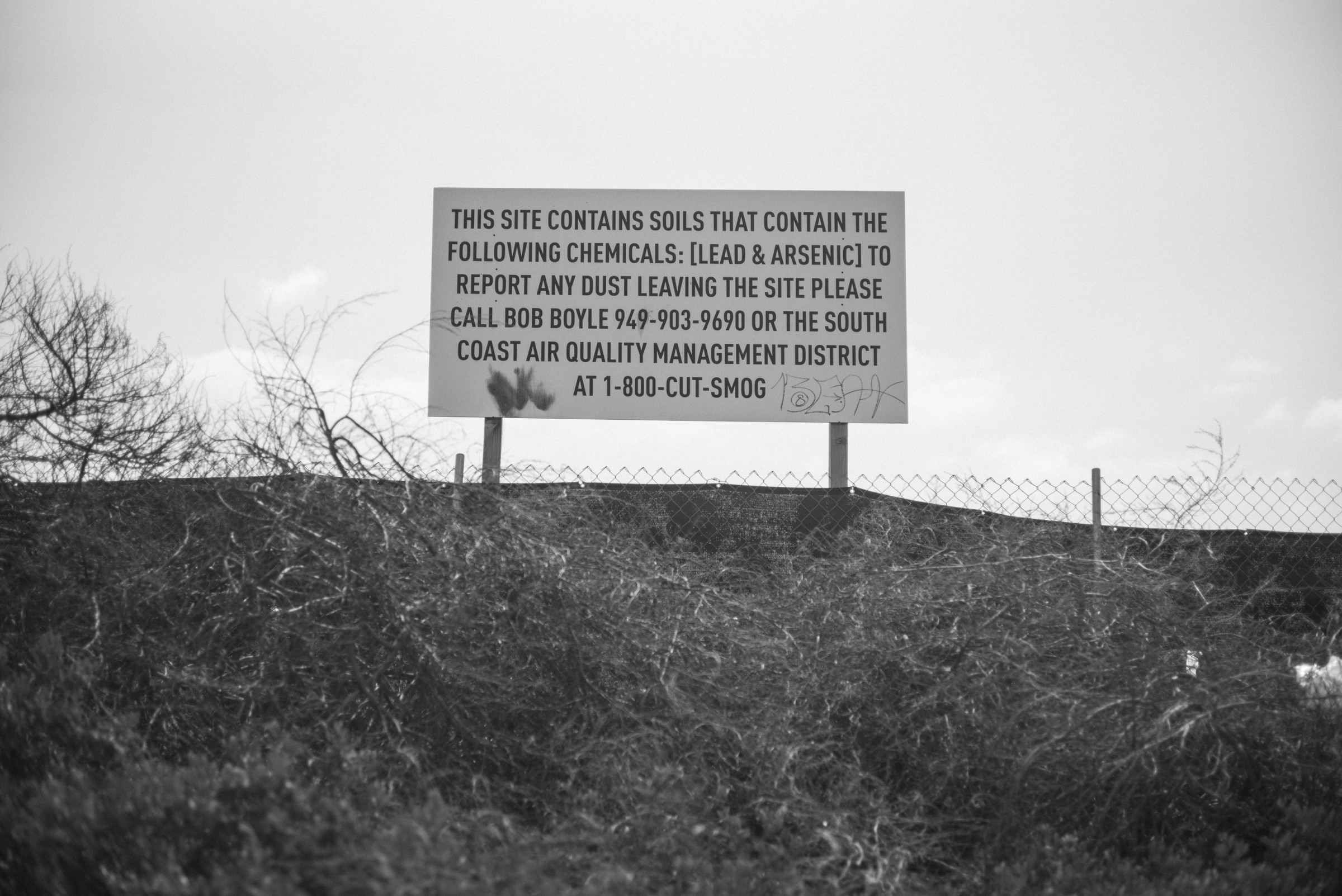

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the L.A. region, which includes Long Beach, has a population of nearly 18 million people. Population growth influences the health of the L.A. River and surrounding communities. Here, a billboard next to a development site near the L.A. River indicates that the site contains contaminated soil.

Damon cleans the fleas off of his dog, Barney, in the L.A. River, where he has lived for 10 years, he said.

Jose stands in the L.A. River near Sepulveda Dam, where he comes to relax and bathe his dog Snoopy. This section of the river is susceptible to high bacteria levels.

Tilly Hinton, 42, founder and curator of Los Angeles River X, a digital storytelling project, stands for a portrait on the concrete next to the L.A. River. “About 3.5 million barrels of concrete got poured into this river from 1938 until the late 50s,” Hinton said. “What endangers the river is that we don’t respect its importance.”

A woman who lives along the L.A. River bathes in the water, which is susceptible to high bacteria levels.

Where the L.A. River joins the Pacific Ocean, the Golden Shore Marine Biological Reserve faces a backdrop of highways and port infrastructure. The reserve originally existed at the mouth of the river, before being re-established in a more isolated area. Despite the presence of litter, the reserve is one of the few and most important wildlife preservation areas along the L.A. coastal region.

Pablo Unzueta

Pablo Unzueta is the recipient of Circle of Blue’s inaugural Water & Climate Fellowship program, supported by Aqualateral.

The fellowship elevates diverse and up-and-coming journalistic talent to report on environmental justice, social inequality, and water inequality in the United States.

Pablo Unzueta recently graduated from California State University, Long Beach. With a background in photojournalism, his work has been featured in Dig Magazine En Español, CalMatters, and the Daily Forty-Niner.

© 2025 Circle of Blue – all rights reserved

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy