In Winberg, residents have to boil their water or risk falling ill.

Residents of a new informal settlement outside Winburg gather to fill containers with water from a pipe supplied by the municipality. Sana Ntho, 54, said the water either has to be boiled or disinfected before drinking. With no electricity available, and firewood a scarce commodity, she adds a spoon of bleach to every 20-liter bucket of water.

By Steve Kretzmann, CCIJ — August 25, 2022

Photos by Steve Kretzmann

Data visualizations by Yuxi Wang

Having spent much of his adult life working in the coal mines in Welkom, pensioner Hendrik Tlaudi says he now suffers from a bad back and must take medication on a daily basis. But Tlaudi, who lives in a state-subsidized house with his widowed sister in Winburg, about an hour from the mines, cannot simply pour a glass of water from the tap to swallow his pills.

Like everyone else in this town in South Africa’s Free State, he has to boil tap water first. Since the municipal water supply is often contaminated with bacteria from human feces, he risks getting diarrhea and stomach cramps if he doesn’t do so.

And like most people living in the poorer section of the town, who survive on meager state pensions and grants, Tlaudi’s household does not always have enough money to buy the electricity or paraffin needed to boil the water. On those occasions, he says, his sister’s two teenage children have to scrounge the surrounding countryside for firewood to burn.

Part of the reason Winburg’s water is contaminated is because the effluent released from the wastewater treatment works flows directly into the dam used for the town’s drinking water. This would be acceptable if the sewage was properly treated, and if the water purifying plant at the dam was functioning properly.

However, when this reporter visited the wastewater treatment works in March, it was completely broken down, and the water purifying plant was dilapidated. Official entry to the plant was barred, but from the outside it was clear that standard building maintenance had not taken place. Shrubs and small trees could be seen growing from the gutters and cracks in the walls.

Hendrik Tlaudi stands at the gate to his property in Winburg. Tlaudi needs to take medication on a daily basis, but the municipal water needs to be boiled before he can use it to swallow his pills.

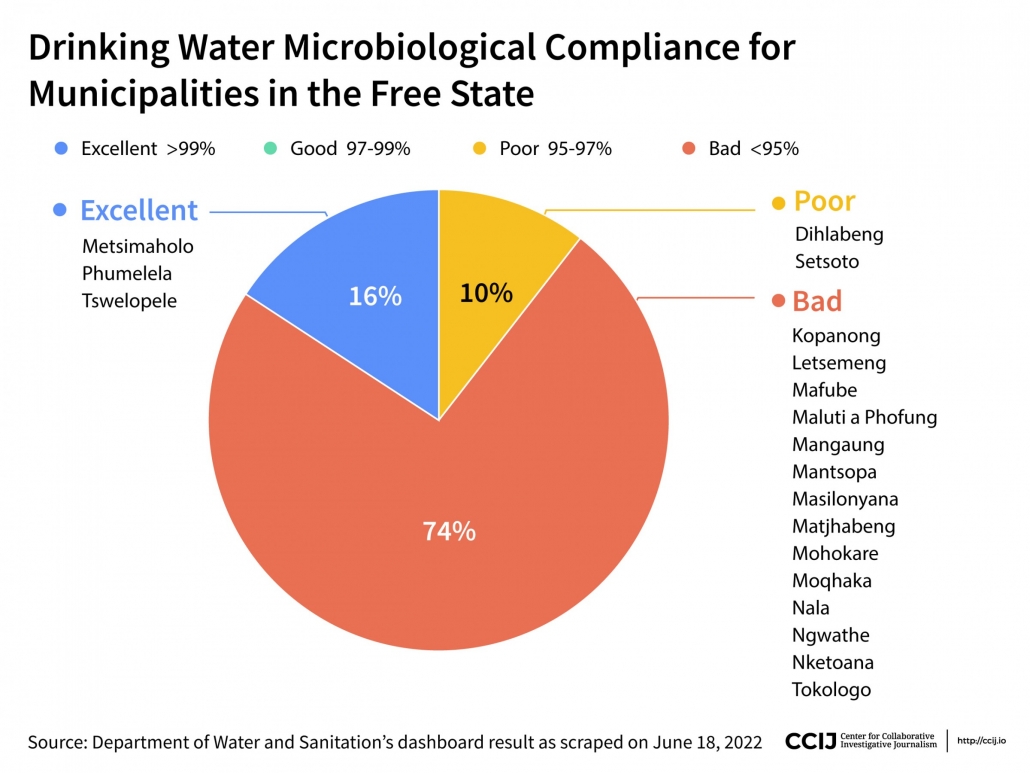

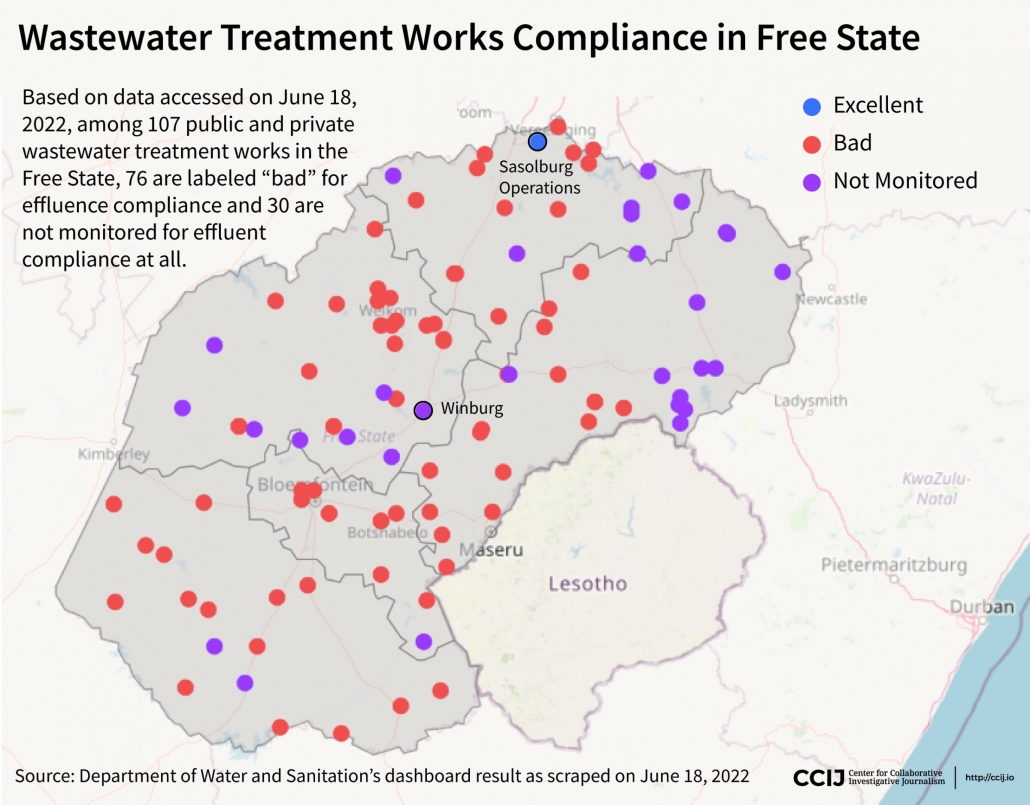

Data from the national Department of Water and Sanitation (DWS) Integrated Regulatory Information System (IRIS) shows that wastewater treatment works in Winburg and beyond are, in the words of the latest Green Drop report – a regulatory audit of the country’s wastewater treatment works – in a “critical state.” The report goes on to say they “need urgent intervention for all aspects of the wastewater services business.”

There are three quality indicators for the effluent released from the sewage works into the environment: microbiological compliance, indicating the concentration of fecal bacteria; chemical compliance, indicating the concentration of chemicals which negatively impact ecosystems; and physical compliance, indicating electrical conductivity and oxygen demand.

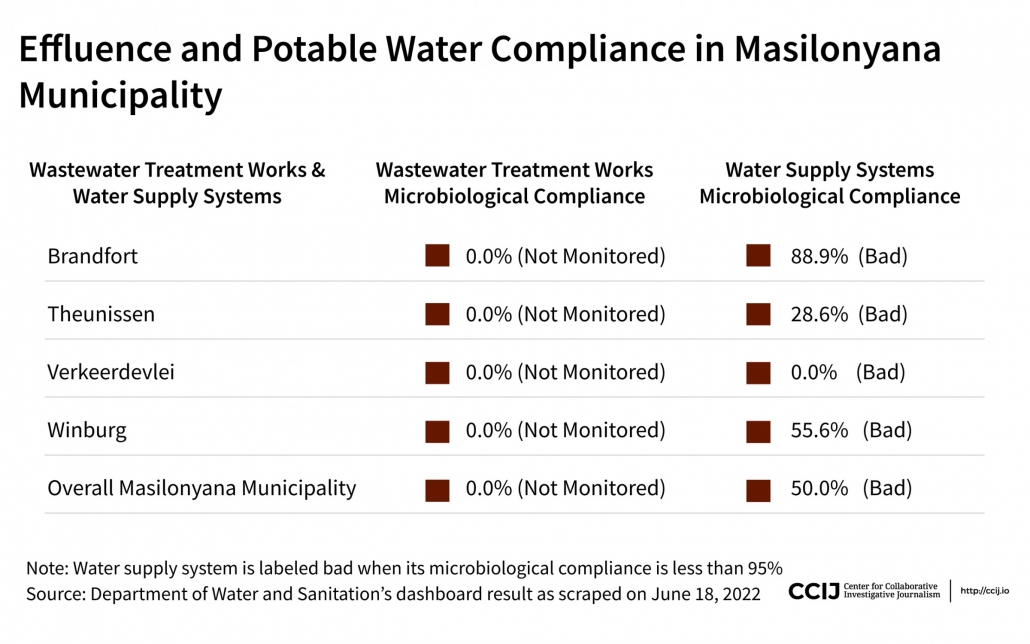

The Winburg wastewater treatment works, as of June 18, scored 0% for all three indicators on the IRIS dashboard. This is indicative of the municipality not achieving the basic requirement of providing regular test results to the regulator.

It did not fare much better on the drinking water front. Data publicly available on the IRIS dashboard shows Winburg’s municipal water supply currently meets national microbiological quality guidelines just 55.6% of the time. Worse yet, it complies with disinfectant standards just 11.1% of the time.

A municipal worker at the wastewater treatment works, who could not be named because he was not authorized to speak to the media, pointed out a critical pump in need of a fan belt, saying the pump had not been working for three weeks. Similarly, the aerator pump did not have a fan belt, and the sludge remover did not have a hose.

“All I can do is add chlorine,” the worker said, but he noted that what could be seen running through the plant came from the storm water system filled by recent rains. The filthy water was flowing through the sewage ponds, stirring up the sludge and flowing out to the dam.

Some sewage wasn’t even getting to the wastewater treatment works, he said. It was flowing to the dam from a broken down pump station further up the line.

Trash, algae and other debris float in open air containment vessels at the dilapidated wastewater treatment plant in Winburg. The plant was recently rated as being in a “critical state,” scoring a 0% on a scale of quality indicators from the Department of Water and Sanitation Integrated Regulatory Information System.

The water treatment plant responsible for water purification in Winburg was awarded a refurbishment contract worth R25 million ($1.5 million) last year. And yet, it has shrubs and grass growing from the gutters and cracks in the walls.

A contractor, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said he oversaw upgrades to the sewage pump stations and refurbishment of the wastewater treatment works in 2020. As part of the contract, the company installed a generator at the wastewater treatment works to ensure it continued to function during load shedding.

He said after the company completed the work, which included fixing the aerators essential to purifying the sewage, “some genius” in the municipality decided to move the generator to another facility. However, the electrical lines ran through the generator, so without it there was no power, and the wastewater treatment works could not function. Masilonyana municipality spokesperson Zongezile Ntjwabule said the generator was moved due to “an electrical crisis” that occurred in nearby Brandfort.

Rewiring it was a simple job of reconfiguring the incoming line, which any qualified electrician could do, the contractor said. Yet this had not been done. Ntjwabule said the municipality is currently working to address the “faulty cables,” responsible for cutting off power supply to the Winburg wastewater treatment plant.

The contractor added that the company advised the municipality it needed to replace the town’s sewerage pipes, which were old asbestos-laden pipes that were continually rupturing. “They were breaking in people’s yards,” he said.

All effluent from the wastewater treatment works, as well as sewage from broken sewerage lines and pump stations, flowed to the dam where drinking water was drawn. But even if the water purifying plant at the dam was working properly, it wasn’t designed to clean water contaminated by sewage, he said.

The stream of effluent runoff, which smells strongly of sewage, flows from Winburg’s failing wastewater treatment works to the dam from which the town’s drinking water is extracted.

Jane is a Communications Associate for Circle of Blue. She writes The Stream and has covered domestic and international water issues for Circle of Blue. She is a recent graduate of Grand Valley State University, where she studied Multimedia Journalism and Women, Gender and Sexuality Studies. During her time at Grand Valley, she was the host of the Community Service Learning Center podcast Be the Change. Currently based in Grand Rapids, Michigan, Jane enjoys listening to music, reading and spending time outdoors.