SWOT mission aims to fill global gaps in key water data.

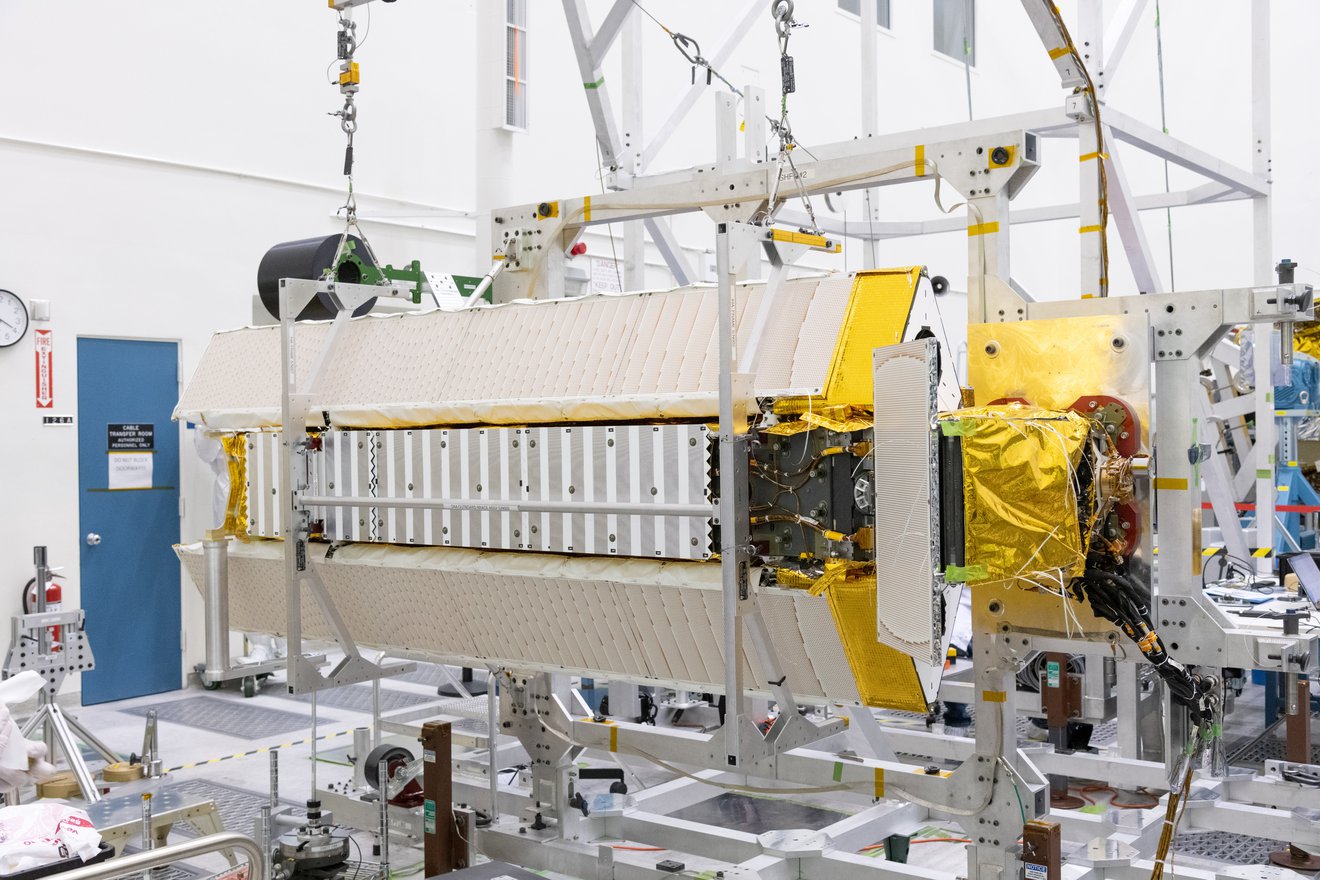

Part of the Surface Water and Ocean Topography (SWOT) satellite’s science instrument payload sits in a clean room at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory during assembly. Photo courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue – November 14, 2022

By foot, horse, and canoe, European explorers centuries ago undertook years-long expeditions to document the length and breadth of major rivers.

Today, satellites make the first pass of discovery. Though rivers meander and melting glaciers birth new lakes annually, the world’s major drainages have largely been mapped.

Yet one fundamental dimension remains largely a mystery: the rise and fall of water bodies globally. Accurately measuring, at low-cost, the weekly changes in rivers, lakes, and wetlands would allow scientists to observe how much water moves through them. Land-based gauges do some of this work. But where gauges are scarce — Alaska, Africa, Asian headwaters — these numbers are inaccurate or unknown. The answer holds implications for flood prediction and drought response — even international diplomacy.

The vessel for this new knowledge is the Surface Water and Ocean Topography satellite, a joint venture between NASA and the French space agency Centre National d’Études Spatial, with contributions from the Canadian Space Agency and the UK Space Agency. Planned for nearly two decades, the mission is scheduled to launch on December 12 from Vandenberg Space Force Base, in California.

“It’s going to be completely unprecedented,” said Tamlin Pavelsky, who is in charge of the mission’s water science team.

Satellites belong to a field of observational science called remote sensing. Having eyes in the sky, either on airplanes or spacecraft, is transforming environmental monitoring and management. Reporters used satellite images from companies like Maxar and Planet Labs to pinpoint water systems in Ukraine that were damaged by Russian airstrikes. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is leading a coalition to develop a satellite-based program to detect toxin-producing algae in lakes. Instruments installed on the International Space Station are refining weather forecasts by measuring water vapor in the atmosphere and water held in clouds. Scientists are exploring satellite-based measurements of plant productivity as a way to anticipate quick-forming “flash” droughts.

Satellites, like traffic cameras, can catch people breaking the rules. California regulators police water use with an open-source program from OpenET. Incorporating satellite data, the program estimates water that plants “breathe” into the atmosphere and water that evaporates from farm fields. This information, coupled with a database of planted crops, indicates whether farmers are exceeding their allotment of irrigation water. On land, watchdog groups point satellites at natural gas fields to reveal production wells that leak methane. At sea, they track illegal fishing.

SWOT, which will measure ocean currents in addition to freshwater flows, will be the latest entrant into this hall of remote sensing champions.

Pavelsky, a professor in the department of earth, marine, and environmental sciences at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, is giddy about the mission and the knowledge it will generate. The drying of the American West, for instance, has revealed the precariousness of reservoirs.

“If you’re a water manager in a region, and you need to know how much water you have available, or how that’s changed over time, we’re going to be able to tell you that in ways that that we’ve never been able to do,” Pavelsky said.

For oceans, SWOT will track small-scale currents and eddies that transport nutrients, salt, and heat. This information will be useful for understanding the ocean’s role in a changing climate.

For rivers, instruments on the satellite will map how floods move across the entire watershed, which is helpful for modeling future inundations. It will also, for the first time, provide a relatively accurate estimate of the water flowing in the world’s major rivers.

“We think that’s absolutely critical,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, head of science at NASA. “The currency of the future is water, and it’s those types of spacecraft that are needed to understand and help utilize it the right way.”

The equipment is so sensitive that it will detect water level changes in the roughly 2 million lakes larger than 250 meters by 250 meters. That’s a surface area equal to a cluster of about 11 football fields. The hope is that the instruments can survey smaller lakes that are 100 meters by 100 meters. The number of lakes measured would then increase to 6 million. Rivers wider than a football field is long will be surveyed, too.

SWOT will pass over sites every week to 10 days. Due to the orbital path, locations closer to the poles will be monitored more frequently than those near the equator. This interval means that SWOT excels for large-scale watershed changes, like the historic floods earlier this year that submerged one-third of Pakistan. SWOT won’t detect changes in creeks or a flash flood that arises after an hour-long downpour. And it won’t transmit data every 15 minutes like a U.S. Geological Survey river gauge. But for large swathes of the world that are essentially a blank space for hydrological information, the mission will be a revolution.

A data revolution energizes scientists like Pavelsky. But data is also power. And data about water is occasionally guarded as a matter of national security. How SWOT will influence the political balance of power is a question that Faisal Hossain is tasked with understanding.

A University of Washington professor and hydrologist, Hossain leads the applications team investigating how people will use SWOT data.

Political sensitivities are an important consideration. Countries in the headwaters of major rivers might not share information with downstream neighbors about reservoir operations. Hoarding water is not a good look. Egypt has raised concerns about the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam in Ethiopia and how the dam will affect its access to water from the Nile. In the Mekong basin, Thailand filed a complaint with a regional consultative body in 2020 about China’s dams in the river’s upper reaches.

SWOT will pull back the veil of secrecy. Two research projects affiliated with the mission focus on the Nile and Mekong basins. Hossain said verified, publicly available data act like “an independent jury” and could put countries on more even footing.

“It’s kind of like the internet – it democratizes access to water information,” he said.

Hossain recently returned from a trip to Jordan, where he met with Iraqi officials to discuss water issues. The Iraqi officials, he said, were interested in how much water is being held in reservoirs in southeastern Turkey, on rivers that flow into Iraq. Satellite data that reveals seasonal storage changes in the reservoirs would “help them prepare better,” Hossain said. “But also in driving negotiations for water sharing.”

SWOT team members are excited about the upcoming launch because they’ve spent a large portion of their careers nurturing the project. Hossain joined the team in 2008. Pavelsky started even earlier, attending his first SWOT development meeting in 2004, when he was in graduate school.

Once the satellite is in orbit the work doesn’t stop. Data — terabytes per day — will be transmitted starting in March. But it won’t be usable until late summer 2023 at the earliest. First it must be verified for accuracy. Doing so is not a desk job. Pavelsky said that teams will fan out across the globe — the Rhine River, Willamette River, Sierra Nevada lakes, rivers in Alaska, French Guiana, and Madagascar — to measure lake levels and river flows on the ground and compare those results to the SWOT output.

Pavelsky, who recognizes the political sensitivity of the data, will monitor the Waimakariri River, a braided waterway in New Zealand.

“We need to get SWOT data to a place where people really trust it,” Pavelsky said. “And so I think the validation work that we’re going to do is going to be absolutely key.”

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton