https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/2022-05-04-Arizona-Lake-Powell-aerial-JGanter-5704-Edit2500.jpg

1601

2400

Brett Walton

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Brett Walton2022-08-16 20:03:202022-12-08 22:12:31Colorado River States Face Deeper Water Cuts – With More on the Way

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/2022-05-04-Arizona-Lake-Powell-aerial-JGanter-5704-Edit2500.jpg

1601

2400

Brett Walton

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Brett Walton2022-08-16 20:03:202022-12-08 22:12:31Colorado River States Face Deeper Water Cuts – With More on the WayThe Year in Water, 2022

Sharpening the Shark’s Teeth

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue – December 13, 2022

Spend a few days at a water conference and you’ll hear a favored metaphor for the environmental changes that are unsettling the planet.

If climate change is a shark, attendees will say, then water is the shark’s teeth. In this telling, when higher temperatures bite, victims are likely to suffer a hydrologic trauma: too much water or too little. Floods wash away homes; droughts kill livestock and crops.

The strength of the shark’s teeth and the breadth of the bite were on full display in 2022.

Ferocious monsoon floods submerged one-third of Pakistan, devastating the agriculture sector in Sindh province, displacing 8 million people, and killing more than 1,700. A third consecutive year of the La Niña weather pattern was a calamity for the Horn of Africa, where parts of Somalia are on the verge of famine for the second time this century.

Economies were not spared. Low water on the Rhine and Mississippi rivers halted barge traffic and drove up shipping costs on two of the world’s most important commercial waterways. The big reservoirs on the Colorado River continued to shrink as a warming climate and inadequate conservation dry out the basin. European glaciers suffered startling losses in ice coverage during intense summer heat that caused French towns to run out of drinking water.

Betraying its carefree reputation, summer became a season of dread as cloudless days and broiling heat underscored the fragility of water-dependent energy systems. In August, French regulators suspended thermal pollution standards for rivers, allowing nuclear plants to overheat streams. The same month Chinese authorities closed Toyota and Foxconn factories in Sichuan province, a leading manufacturing center, after a record-breaking heat wave curtailed hydropower output and strained the electric grid.

Two weeks ago, the Zambezi River Authority ordered the operators of Kariba Dam to halt hydropower generation through at least January 2023, worsening electricity shortages in Zimbabwe and Zambia. The dam’s reservoir, the world’s largest at maximum storage, is less than 3 percent full.

Each year delivers tales of the largest, driest, and worst. In many ways the superlatives are derived from a fevered atmosphere. But the consequences are due not only to powerful storms. They are also a result of poor decisions about where to build, what to subsidize, or how to allocate land and water.

Though vivid, the shark metaphor is an inadequate frame for some of 2022’s defining water stories.

- Russian forces attacked Ukrainian infrastructure, leaving millions of civilians in Kyiv and Kherson without heat or running water. Legal scholars called the targeting of essential infrastructure a violation of international law.

- Cholera erupted worldwide, with cases reported in 29 countries, including large outbreaks in Haiti, Malawi, and Syria that resulted in a vaccine shortage. To conserve supplies, the group of health agencies that coordinates global vaccine distribution began administering one shot instead of the typical two doses.

- Another failure of seasonal rains in the Horn of Africa pushed Somalia to the brink of famine. Food distribution was not helped by simmering local conflicts that obstructed aid work and global grain markets that were disrupted by Russia’s war against Ukraine. More than half of children under age 5 now face acute malnutrition, a developmental setback that results in severe weight loss or death.

- South Africa’s municipal water systems are in disarray, buffeted by a warming climate while enduring a miasma of leaky pipes, outages, and rationing.

A climate shark is fearsome enough for water. But bad economic, managerial, and political choices serve to sharpen the teeth and deepen the bite.

John Matthews, the executive director of the Alliance for Global Water Adaptation, calls it “a crisis in decision making.” Disasters are horrific and noteworthy. But, in his mind, they can distract from the grinding work of establishing new policies and laws to redirect society.

“If the story is impacts and disaster and not resilience, then collectively, as voters and politicians, we’re not seeing the actionable and useful story,” Matthews said.

He sees new ideas stirring. Countries are thinking about water in their national climate adaptation plans, where they need to incorporate responses to immense, society-altering water considerations — the disappearance of glaciers, failures of seasonal rains, rising seas. With the UN climate summit hosted by Egypt this year, he said Middle Eastern countries became especially keen to understand the crucible conditions of a water-scarce future.

“Water will be the language in which this resilience work takes place,” Matthews said.

There are ways, if not to tame the shark, then at least to blunt the teeth. Unless public officials and business leaders make better decisions, the morbid cycle of damage and loss will repeat and repeat.

Below is a sampling of the reports Circle of Blue posted this year investigating the world’s biggest water challenges.

Colorado River Basin’s Moment of Reckoning

It was perhaps the shock that Colorado River users needed.

A basin that is spending down its water savings was jolted in June when the U.S. government ordered the seven states to correct a longstanding misalignment of water supply and demand.

Camille Touton, commissioner of the Bureau of Reclamation, told the states to cut their take from the river next year by between two million and four million acre-feet of water. At the high end, that equals one-third of the Colorado’s recent annual flow. Unless the states acted, she said, the federal government would “protect the system” and apply its own remedy.

John Entsminger, the head of the Southern Nevada Water Authority, which supplies the Las Vegas area, affirmed the groundbreaking nature of the pronouncement. The requested conservation volumes, he said, were of a magnitude “previously considered unattainable.”

They still haven’t been attained. The states missed an August deadline and remain in fractious negotiations about how to divide the cuts.

Lake Mead, absent unprecedented action or a miraculous winter, remains in peril. It is projected to shrink more than 20 feet by the end of 2023, when the reservoir would be just 22 percent of capacity.

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/2022-05-04-Arizona-Lake-Powell-aerial-JGanter-5704-Edit2500.jpg

1601

2400

Brett Walton

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Brett Walton2022-08-16 20:03:202022-12-08 22:12:31Colorado River States Face Deeper Water Cuts – With More on the Way

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/2022-05-04-Arizona-Lake-Powell-aerial-JGanter-5704-Edit2500.jpg

1601

2400

Brett Walton

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Brett Walton2022-08-16 20:03:202022-12-08 22:12:31Colorado River States Face Deeper Water Cuts – With More on the Way

The Bureau of Reclamation’s $4 Billion Drought Question

Arizona and California Farmers, Targets for Colorado River Cuts, Draft Their Conservation Strategy

A Colorado River Glossary: Jargon Explained

What Happens If Glen Canyon Dam’s Power Shuts Off?

Severe Drought Challenges the American West

The Great Salt Lake dropped to a record low. New Mexico witnessed its largest wildfire, which burned 341,000 acres east of Santa Fe. Wells in California’s Central Valley produced dust, not water.

The western states continued to dry as climate-induced warming gobbled the region’s snowpack before the meltwater could enter rivers or reservoirs.

There were small steps to counteract the damage. Las Vegas led the way in prohibiting ornamental turf in medians and office parks.

Acknowledging that wells are going dry, residents in southeastern Arizona’s Cochise County voted to enact restrictions on groundwater extraction in Douglas basin. A similar initiative to regulate groundwater in nearby Willcox basin did not pass.

The big questions — large-scale reductions in water use, re-examining what crops are grown where — remain unanswered as the region enters a pivotal winter expected to deliver below-average precipitation.

In New Mexico, Partners Collaborate to End Siege from Megafires

Big Water Pipelines, an Old Pursuit, Still Alluring in Drying West

Drought’s Spillover Effect in the American West

Arizona’s Future Water Shock

At Peak of Its Wealth and Influence, Arizona’s Desert Civilization Confronts A Reckoning Over Water

Toxic Algae Trouble Lake Erie

Harmful algal blooms now rank with climate change as a systemic ecological threat and a severe public policy challenge.

In a six-part series, Circle of Blue investigated the causes, impediments, and solutions to harmful algal blooms that foul Lake Erie’s western basin — and a growing number of lakes in Michigan — every summer.

The series found that ending toxic blooms is eminently achievable. But current practices in Michigan and Ohio are not working.

Ending the scourge of harmful blooms requires significantly reducing the amount of phosphorus applied to the land and draining into water. That will require extensive changes in how the nation produces food, in tandem with much greater accountability by the farm sector, new regulations, and significant increases in public investment.

Remedies for Harmful Algal Blooms Are Available in Law and Practice

Powerful Industry’s Torrent of Manure Overwhelms State Regulators

In A Year of Water Quality Reckoning, National Imperative is Impeded

Farms in Six Southeast Michigan Counties Are Major Sources of Lake Erie Toxic Blooms

Danger Looms Where Toxic Algae Blooms

Climate Change Brings Water Extremes

The number was so large it seemed to be a misprint. Satellite images revealed that one-third of Pakistan was submerged in August after ferocious monsoon floods. The inundation scattered millions of people away from their homes and obliterated crops. A needs assessment estimated the financial damage at $15 billion.

Pakistan and other locations experienced extremes in a third consecutive La Niña year.

Europe baked in a heatwave that scorched cities, depleted rivers, and deprived rural communities of drinking water. French authorities trucked water to more than 100 towns.

China marked its strongest and longest heatwave as the temperature climbed above 40°C (104°F). Scott Moore, a China scholar at the University of Pennsylvania, said that climate change is now one of the biggest risks for the world’s second largest economy — and largest carbon emitter.

New Satellite Will See Water’s Big Picture

As Flood Waters Recede in Pakistan, ‘Second Wave’ of Disaster Strikes

Eastern Kentucky Floods Continue Cycle of Poverty

What Does Water Want? A Conversation with Author Erica Gies

IPCC Climate Report: Six Key Findings for Water

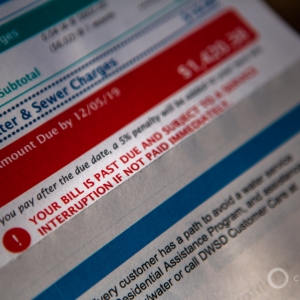

U.S Water Access and Affordability

Income inequality in the United States and the rising cost of maintaining aging water systems conspire to make monthly water payments a burden for many low-income households.

A lauded federal program to help these households pay their water bills — the first time that Congress designated money for the problem — began distributing funds. But it was slow to start and its future is uncertain.

Utilities and entire communities, like those in rural Nebraska, are seeing the cost of water treatment increase in order to remove contaminants like nitrate and PFAS.

Slow to Start, Federal Water Bill Assistance Program Ramps Up

Lake Erie’s Failed Algae Strategy Hurts Poor Communities the Most

High Cost of Water Hits Home

Inflation Weighs On U.S. Water Utilities

Nebraska Agrochemical Contamination Throws Families, Communities, Water Providers into Turmoil

New Money for U.S. Water Infrastructure

Congress in the last two years opened the public purse for U.S. water systems, providing federal funding at levels not witnessed in a half century.

Cities, tribes, and states had the option of spending a portion of their $350 billion in pandemic relief funds on water and sewer upgrades. Many chose to do so.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency began distributing the $50 billion for water systems that was a part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Polluted legacies were undone. Newark, New Jersey, finished removing more than 23,000 lead service lines in the city, a process that took under three years. Another majority-Black city with high-profile lead contamination — Benton Harbor, Michigan — nearly completed its lead pipe removal. Only a few dozen remain in the ground.

Yet amid the spending notable problems persisted. The water system in Jackson, Mississippi, failed during heavy rains in August. Some 160,000 people were without running water for a week.

Scholars say such failures contribute to a rise in public distrust of tap water and government, especially in poor and marginalized communities.

Tap Water Failures and Distrust of Government: A Conversation with Manny Teodoro

Q&A: Do We Have to Choose Between Speedy Development and Environment?

Michigan’s ‘Very Big Opportunity’ in Infrastructure Windfall

After Decades of Neglect, Bill Coming Due for Michigan’s Water Infrastructure

Billions Flow to Water Systems from Federal Pandemic Relief Funds

Polluted Water Damages Health, Ecology, Economy

Contaminated water continues to wreak havoc on ecosystems and human bodies.

Cholera outbreaks, caused by dirty water, strained the global vaccine supply after cases were discovered in at least 29 countries.

“Within the countries reporting outbreaks, we are seeing a worsening,” according to the World Health Organization. “Not only do we have more outbreaks but the outbreaks themselves are larger and more deadly.”

In Nebraska, researchers investigated the links between exposure to toxic farm chemicals and high rates of pediatric cancer in the state.

Rising seas pushed saltwater inland, rendering drinking water wells on the U.S. Atlantic Coast unusable.

Mine Cleanup Law Weakened By Coal’s Decline

“Fighting for Inches” in the Southeast’s Struggle With Salt

Saltwater Intrusion, a “Slow Poison” to East Coast Drinking Water

Concrete River

Is Agrochemical Contamination Killing Nebraska’s Children?

Conflicts Upend Water and Food Systems

After Russia invaded Ukraine in February it was not long before Vladimir Putin’s forces began targeting water and energy systems. Residents of Kherson and Kyiv queued for water after power outages shut down treatment and pumping plants.

The invasion of one the world’s most important grain exporters also rattled global food markets.

The disruption echoed in the Horn of Africa, where a fifth subpar rainy season has set the region on edge. Crops have withered, hunger abounds, and militants impede the distribution of food aid.

Parts of Somalia are on the cusp of famine. Such a declaration is unusual. The last famine in Somalia occurred in 2011, when about a quarter-million people died.

Michael Dunford, who leads the World Food Program’s work in the Horn of Africa, warned that the situation would not improve until rains returned.

“Unfortunately, we have not yet seen the worst of this crisis,” Dunford told UN News. “If you think 2022 is bad, beware of what is coming in 2023. What that means, is that we need to continue to engage. We cannot give up on the needs of the population in the Horn.”

War in Ukraine, Drought Converge to Worsen Hunger Crises in Horn of Africa

An Encroaching Desert Intensifies Nigeria’s Farmer-Herder Crisis

Unsafe Yield

War in Ukraine Lengthens List of Violent Acts over Water

HotSpots H2O

Water is both a source of tension and a casualty of war. In the end, it is the people who suffer.

Circle of Blue’s weekly HotSpots series highlights areas in which water access plays a role in civic upheaval and armed conflict.

Protesters in France clashed with armed guards that the government dispatched to protect the construction site of proposed farm irrigation reservoirs.

The biggest water-conflict story unfolded in Ukraine, where Russian forces targeted water and energy infrastructure.

HotSpots H2O: As Floods Subside, Pakistan’s Economy Is on a Knife-Edge

HotSpots H2O: “Day Zero” Looms for South African Province

HotSpots H2O: As Water Systems Fail in Pakistan, Heat Wave Begets A Health Crisis

HotSpots H2O: ‘We Have Nowhere Left To Go’: Durban’s Affordability Crisis Pushed Development into Flood Zones

HotSpots H2O: In Chile’s Lithium Mines, Climate and Environment Are Dueling Priorities

Images:

Canal south of Cairo, Egypt © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Lake Powell, Utah © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Houseboats on Lake Powell © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Luna Pier, Michigan © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Dust in northeastern Arizona © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Cecily McClellan, co-founder of We the People of Detroit © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Port Huron, Michigan, water treatment plant © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Families in Aurora, Nebraska © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Field south of Cairo, Egypt © J. Carl Ganter / Circle of Blue

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton

Related

© 2025 Circle of Blue – all rights reserved

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy