Water’s True Cost: In Photos

The quality of Michigan’s water infrastructure and the consequences of failure, while still real and apparent, are no longer being ignored.

Photos by J. Carl Ganter, Circle of Blue — May 23, 2022

Throughout the Great Lakes region and across the U.S., water systems are aging. In some communities, this means water bills that residents can’t afford or water that’s unsafe to drink. It means that vulnerable systems are even more at risk in a changing climate. From shrinking cities and small towns to the comparatively thriving suburbs, the true cost of water has been deferred for decades.

As the nation prepares to pour hundreds of billions of federal dollars into rescuing water systems, the Great Lakes News Collaborative investigates the true cost of water in Michigan.

This is the first of a ten-part series.

Water towers, like this one in Akron, Michigan, are the most visible manifestations of a community’s water system. Essential pieces of civic infrastructure, water systems across the state need repairs.

Kaleb Danndels directs an excavator during a water main replacement project in Pontiac, Michigan.

Michigan cities rich and poor, big and small have spent decades delaying maintenance on water systems. Now, the bills are coming due.

Six years after a panel of experts concluded that the state’s public works were in “a state of disrepair,” the quality of Michigan’s water infrastructure and the consequences of failure are no longer being ignored.

Damon Collins, an underground laborer, works for Pamar Enterprises, Inc., the project contractor for a water main replacement.

The challenge is immense. And playing catch-up after all these years will be costly. But this Water’s True Cost project from the Great Lakes News Collaborative found that the pieces of a new quilt in Michigan, one that reverses the infrastructure decline of recent decades, are starting to align.

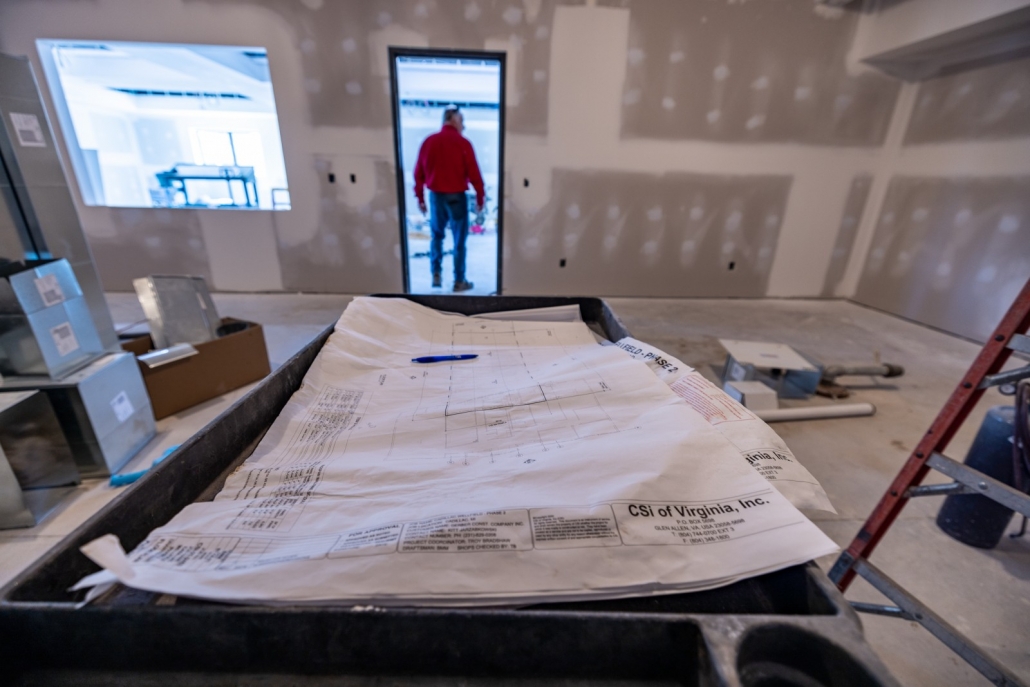

Officials in Cadillac, Michigan have installed three new wells at East 44 Road. The city is also building new maintenance facilities and water department offices.The city received a $9.8 million low-interest loan from the Drinking Water State Revolving Fund to finance the project.

Michigan will receive more than $1 billion in federal funds over the next five years, giving the state an opportunity to reinvest in essential public works at little to no cost for residents.

Cecily McClellan is co-founder of We the People of Detroit and directs the “water works” program, which provides water to Detroit area residents who can’t afford it. “When people can’t afford water, it becomes a health issue,” she said, “that affects the most vulnerable, especially young mothers.” Photo: J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

Nonetheless, water rates are rising across Michigan. These are necessary investments for the state’s future that nonetheless are exposing low-income households to financial stress.

Leaders and activists are taking notice.

Once the infrastructure is replaced, the next step is civic repair. Rebuilding community trust, after years of inadequate service or foul tap water, is just as difficult, perhaps more so, than the engineering work. Nonetheless, Michigan’s greatest opportunity for renewal in decades has arrived.

Like living alone in a mansion on a blue-collar salary, some water treatment facilities in Michigan have become absurd to own and impossible to maintain.

A behemoth along the Saint Clair River, the Port Huron water filtration plant is capable of purifying 30 million gallons a day — enough to serve the entire population of St. Clair County, and then some.

It’s true that customers get cheaper, cleaner water when communities share the cost of infrastructure. But while partnerships often make sense on paper Michigan’s experience shows how political conflicts and logistical challenges can complicate the math.

Once infrastructure is replaced, the next step is civic repair. Rebuilding community trust, after years of inadequate service or foul tap water, is just as difficult, perhaps more so, than the engineering work. Nonetheless, Michigan’s greatest opportunity for renewal in decades has arrived.

Water’s True Cost

The Great Lakes News Collaborative includes Bridge Michigan; Circle of Blue; Great Lakes Now at Detroit Public Television; and Michigan Radio, Michigan’s NPR News Leader; who work together to bring audiences news and information about the impact of climate change, pollution, and aging infrastructure on the Great Lakes and drinking water. This independent journalism is supported by the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. Find all the work here.

Related

© 2025 Circle of Blue – all rights reserved

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy