Lake Powell is drying behind one of the Southwest’s largest hydropower plants.

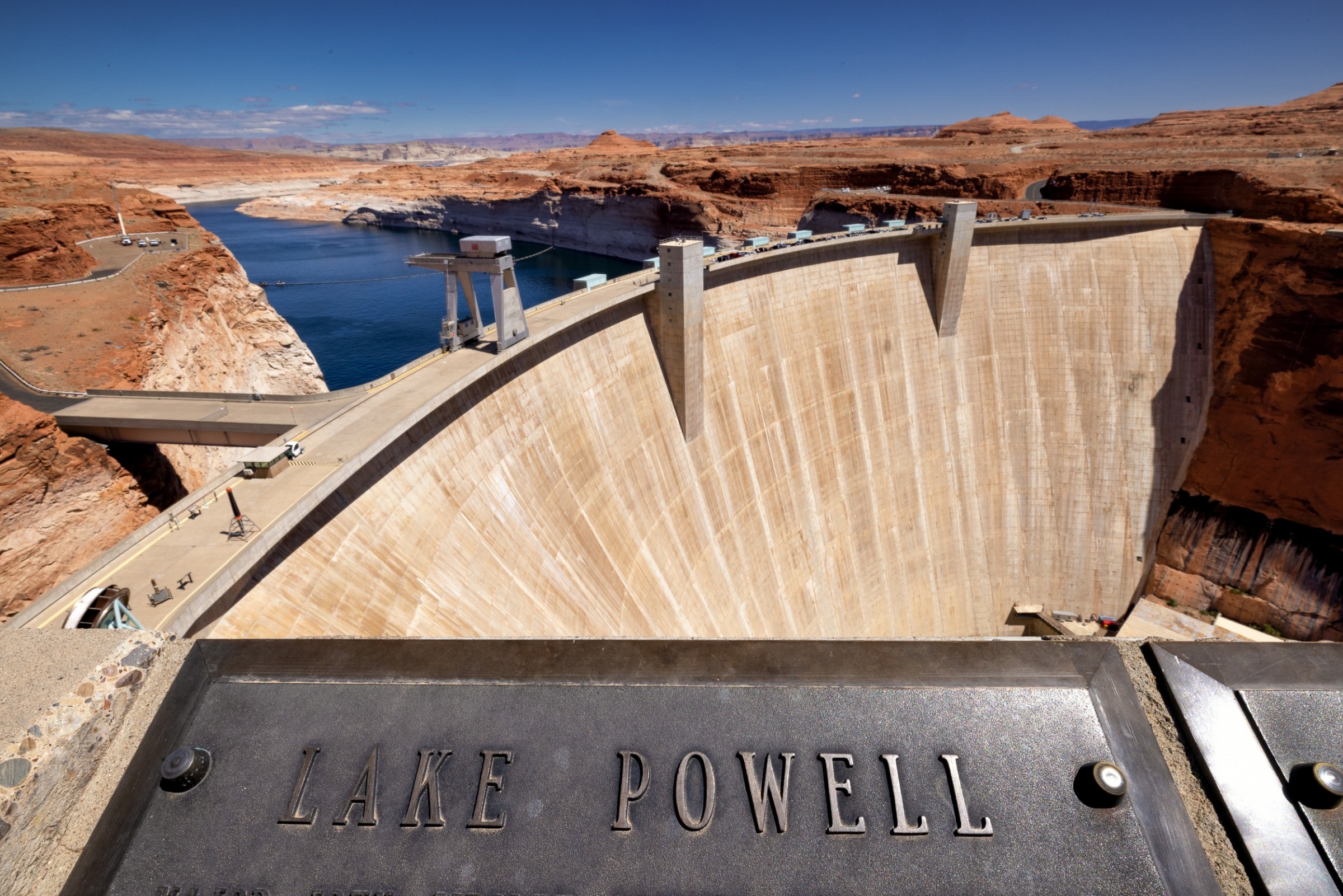

Glen Canyon Dam forms the massive reservoir of Lake Powell. Water in Powell is released through turbines in the dam, generating power that electrifies homes, businesses, rural coops, and irrigation pumps across six states and more than 50 Native American tribes. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue – June 6, 2022

- Glen Canyon Dam is operating at 60 percent of its hydroelectric capacity.

- Hydropower generation will likely shut down when Lake Powell’s elevation drops below 3,490 feet. Currently the lake is at 3,534 feet.

- Besides the kilowatt-hours it generates, Glen Canyon provides key services to the electric grid.

Critics of the Bureau of Reclamation had a favored slur for the concrete and earthen walls that the federal agency raised across magnificent canyons of the Colorado River watershed: cash register dams.

The dig wasn’t wrong, especially during the agency’s mid-20th century construction spree. For decades, hydroelectric dams in the Colorado River Storage Project supplied cheap power and a relatively steady revenue stream from electricity sales that helped repay dam construction and operation costs while also subsidizing crop production and settlement of the American West.

Today, the cash registers are ringing at much lower decibels. Sapped by a warming climate, the grand reservoirs of the Colorado River are in a two-decade decline, dropping low enough that hydropower from one of the grandest, Lake Powell, may soon be in doubt.

The country’s second largest reservoir and a lynchpin in the intermountain electric grid, Powell is more dirt than water these days. The reservoir holds just 27 percent of its full capacity. In April it dropped to a level not witnessed since Glen Canyon Dam was completed nearly six decades ago. Water in Powell is released through turbines in the dam, generating power that electrifies homes, businesses, rural coops, and irrigation pumps across six states and more than 50 Native American tribes.

Lake Powell’s feeble condition is part of a climate reckoning in the West that links water, ecosystems, food production, and energy generation. A drying climate and withering heat in recent years have pummeled the region: water cuts to farmers, dry wells, mass fish and bird die-offs, and depleted reservoirs that have decimated hydropower output.

Glen Canyon Dam is now operating at about 60 percent of its designed hydroelectric capacity, according to Nick Williams, the Upper Colorado River Basin power office manager for the Bureau of Reclamation. Rated for 1,320 megawatts — roughly the size of a large fossil fuel plant — the dam is now capable of only 800 megawatts.

The failure of Glen Canyon Dam to produce hydropower, in isolation, would be bothersome for energy markets but not a catastrophe. It would raise the cost of electricity for 5 million retail power customers, increase greenhouse gas emissions associated with electricity generation, and eliminate key grid-support services that hydropower provides.

But a loss of generating capacity at Glen Canyon at the wrong time — in the summer, for instance, when electricity demands are high — combined with other power station outages could contribute to an electric supply contagion, grid strain, and blackouts in the western states, according to a recent reliability assessment from a national energy watchdog.

Recognizing this, the Department of the Interior took emergency action last month to throw a life preserver at Lake Powell. The Bureau of Reclamation’s parent agency ordered it to hold back more water in the reservoir and at the same time release reinforcement supplies from Flaming Gorge, a smaller reservoir higher in the watershed. Together the actions will add nearly 1 million acre-feet to Powell this year, equivalent to 16 feet of water in the beleaguered reservoir.

Explaining the decision, Tanya Trujillo, the Interior Department’s assistant secretary for water and science, said that the integrity not only of the dam’s power generation but also its water delivery system was at stake if Powell were to breach elevation 3,490 feet — the level at which hydropower generation at Glen Canyon Dam would likely cease.

“In such circumstances,” Trujillo wrote to water leaders in the basin states, “Glen Canyon Dam facilities face unprecedented operational reliability challenges, water users in the Basin face increased uncertainty, downstream resources could be impacted, the western electrical grid would experience uncertain risk and instability, and water and power supplies to the West and Southwestern United States would be subject to increased operational uncertainty.”

Due to declining water levels, Glen Canyon Dam is now operating at about 60 percent of its designed hydroelectric capacity. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/ Circle of Blue

Uncertain, Unstable Times

A dress rehearsal already occurred last summer when Lake Oroville, California’s second largest reservoir, dropped below its minimum power level, and Hyatt Powerplant stopped producing electricity due to low water for the first time in its history. The same fate could await Lake Powell.

Bureau of Reclamation projections indicate the reservoir has a 10 percent chance in the next two years of breaching 3,490 feet. As of June 5, the reservoir’s elevation was 3,534 feet and slowly climbing as melting snow and Interior’s emergency actions contribute to a seasonal rise that has added nearly 12 feet to the reservoir since it bottomed out in April. It is out of the danger zone, for now.

Water users in the Colorado River basin are already feeling the effects of depleted reservoirs. Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir and located on the Colorado River a few hundred miles downstream, also plunged to a record low this spring. A subsequent shortage declaration means that Arizona and Nevada must reduce their withdrawals.

Water reaches Mead by flowing through Glen Canyon. The Interior Department moved this spring to prop up Powell because it worried about Glen Canyon’s water delivery system in low-water conditions. Water is released downstream through the penstocks, which feed the dam’s turbines. If the lake drops too low to produce power, that route is cut off. Water would instead be released through the outlet works, which are untested in extended use as the primary water delivery option.

Glen Canyon’s power customers are also in a pinch.

When Powell drops closer to the 3,490-foot level, operating the dam becomes a game of inches, Williams said. The top of the penstocks — the 15-foot diameter pipes that send water to the turbines — are at elevation 3,477.5 feet. But as the reservoir approaches that level, vortexes could form as water is drawn into the pipes. The violent whorls can injure the dam’s power-generating equipment.

For now, 3,490 feet is the red line because that was the designer’s safe estimate and Glen Canyon was able to generate at that level when Powell was being filled in the 1960s. Even so, Williams, the power office manager, said that Reclamation staff is modeling operational changes to eke out a few more feet of operating range.

The power that Glen Canyon generates is pooled with other federal dams in the upper basin and sold by the Western Area Power Administration. Until last December, WAPA was purchasing power for its customers to compensate for the hydropower shortfall. That model led to a financial cliff.

Due to the expense of market-rate replacement power, WAPA was at risk of depleting the upper basin fund. The fund functions as a checking account, taking in power revenues and paying out costs. Those costs include dam construction repayment and annual dam operations and maintenance. They also include successful environmental programs intended to protect endangered fish in the Colorado and San Juan rivers, reduce salt loads in the river, and make Glen Canyon water releases less damaging to the river corridor.

In 2021, the fund was in jeopardy due to declining hydropower generation. The fund balance was cut in half, dropping from $146 million in January 2021 to $74 million by the end of the year. That resulted in an emergency rate change in December that is expected to stabilize the fund, said Lisa Meiman, a WAPA spokesperson. In most cases, WAPA will no longer buy market-rate power. Individual utilities will shoulder all the added expense. One other action alleviated financial pressure on the basin fund: direct appropriations from Congress to the environmental programs.

Less hydropower will force utilities to look elsewhere for replacement supplies, including from fossil fuel sources. The effect of a hydropower shortfall varies with region, weather, and time of day or year. More coal and natural gas will certainly increase greenhouse gas emissions from the power sector.

But how much? Kelly Sanders of the University of Southern California says the magnitude of a carbon emissions increase due to drought is difficult to calculate, owing to the complexity of electricity supply and demand. The answer is usually only apparent much later, after rigorous data analysis. However, losing a carbon-free source like hydropower means that, all else being equal, the average carbon emissions for electricity goes up.

Customers of Glen Canyon power are confronting those tradeoffs as they search for replacement power.

As a share of its electricity supply, the Navajo Tribal Utility Authority is one of the biggest consumers of Upper Colorado hydropower. In 2020, NTUA acquired 42 percent of its electricity from the Upper Colorado dams.

If power generation forecasts hold true, NTUA estimates that the utility would pay $4.5 million more for electricity this year, according to Srinivasa Venigalla, the deputy general manager. Those costs would be passed on to the utility’s roughly 43,000 residential and commercial customers, he said.

Venigalla hopes Glen Canyon does not go dark. But his utility is preparing in case that day comes. NTUA already has 55 megawatts of solar generation capacity on Navajo lands and another 4 megawatts will come online by the end of this year.

The solar installations won’t completely replace Glen Canyon’s hydropower, Venigalla said. But they will reduce the utility’s purchases of market power.

A diversity of power sources will help other utilities that receive Glen Canyon hydropower. Tri-State Generation and Transmission, a cooperative with 42 utility members in Colorado, Nebraska, New Mexico, and Wyoming, usually acquires 8 percent of its power from the Upper Colorado hydroelectric system.

Lee Baughey, vice president for communications, said that the utility expects its hydropower allocation to drop by a third this year.

“It places pressure on our costs, but we can manage through,” Baughey said.

Households have company in that regard. Roosevelt Irrigation District pumps water to about 38,000 acres in Maricopa County, Arizona. Donovan Neese, the district superintendent since 2011, said retail power customers span the breadth of the county’s agribusiness: cold storage facilities for fruits and vegetables, dairies, cotton gins, and feed mills.

About half the district’s power comes from Glen Canyon and Hoover dams. Neese is in the process of developing the budget for the next fiscal year and did not have exact numbers, but the effect for Roosevelt customers is the same as elsewhere: less hydropower means higher costs.

“That means we continue to advocate for water conservation,” Neese said.

Farm fields near Buckeye, Arizona, where irrigation pumps are partly powered by Glen Canyon Dam. Photo © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

Hydropower as a Service

Glen Canyon’s value extends far beyond the customers. The dam is more than just the kilowatt-hours it generates, said Nathalie Voisin of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory. It also plays an important role in the operation of regional electric grids.

In the southwestern states encircling the Colorado River basin, the majority of power generation is not derived from the force of flowing water. Most comes from fossil fuels, wind, and solar. Nonetheless, hydropower fulfills a valuable niche. Because its generators can deliver electricity quickly — “ramping” in the lingo — hydro bridges the period when solar and wind power wane and before gas-fired turbines can power up. This quick-start capability is especially important when electricity demand is high, such as summer heat waves.

“The economic and reliability values from ramping are very large,” said Voisin, who studies hydropower and its response to changes in climate, season, and technology. “There’s a lot at stake for not being able to get Glen Canyon working for hydropower operation during the summer time.”

Lake Powell, in effect, functions as a large battery, able to be turned on and off to meet fluctuating power demands. Even if Powell were to be drained and the water stored in Lake Mead, as some environmental groups advocate, the grid benefits of Glen Canyon would still need to be reckoned with.

“Glen Canyon cannot be easily replaced with other renewables because Glen Canyon is already critical in their integration into the grid,” Voisin explained. “The replacement technology needs to compensate for the range of grid services provided by Glen Canyon, which is more than capacity and generation. Storage in particular would be needed.”

A rapid increase in water storage behind Glen Canyon is unlikely. Analysts at the Bureau of Reclamation simulate future Colorado River conditions every month. The latest model scenarios show a 10 percent chance that Lake Powell drops below 3,490 feet by April 2024. That’s less than two years away. Not enough days to completely reconfigure the region’s energy services. But plenty of time to ponder a future without Glen Canyon hydropower.

Brett writes about agriculture, energy, infrastructure, and the politics and economics of water in the United States. He also writes the Federal Water Tap, Circle of Blue’s weekly digest of U.S. government water news. He is the winner of two Society of Environmental Journalists reporting awards, one of the top honors in American environmental journalism: first place for explanatory reporting for a series on septic system pollution in the United States(2016) and third place for beat reporting in a small market (2014). He received the Sierra Club’s Distinguished Service Award in 2018. Brett lives in Seattle, where he hikes the mountains and bakes pies. Contact Brett Walton