https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/IMG_1450-2.jpg

1601

2400

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2023-08-30 13:15:192023-12-04 15:57:12Offering Up Advice For Farmers, Universities Add To US Water Pollution

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/IMG_1450-2.jpg

1601

2400

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2023-08-30 13:15:192023-12-04 15:57:12Offering Up Advice For Farmers, Universities Add To US Water PollutionThe Year in Water, 2023

Scenes from the Great Acceleration

By Brett Walton, Circle of Blue – December 12, 2023

The morning before its fearsome winds and formidable rains wrecked the Pacific coast of southern Mexico, Hurricane Otis did not inspire unusual alarm.

Forecasters at the National Hurricane Center, in Miami, were tracking its path. In a 10 A.M. Central Time update on October 24, they sensed that Otis was becoming “better organized,” and though it was classified at the moment as a mere tropical storm, they noted the potential for “rapid intensification.” They expected hurricane status by the time it made landfall later that night or early the next morning. Nothing more than a run-of-the-mill late season cyclone.

In the afternoon Otis shifted gears, like a race car entering a straightaway. Drawing strength from warmer-than-normal coastal waters, Otis morphed within 12 hours from a tropical storm to a Category 5 juggernaut. Forecasters and authorities were caught off-guard. Only one storm in modern times – Hurricane Patricia, in 2015 – had strengthened so quickly. Forecasters changed their tone.

“A nightmare scenario is unfolding for southern Mexico this evening,” the National Hurricane Center wrote in a 10:00 P.M. update. It expected catastrophic storm surge, flooding, and damage around the resort area of Acapulco. That is exactly what happened once Otis hit, in the middle of the night, three and a half hours later.

Such events, while still shocking, are nonetheless more common these days. We live in a superlative era. Rainfall, snowpack, groundwater levels, temperatures, river flows – with greater frequency they are the highest, lowest, or driest. 2023, which is likely to be the hottest year ever recorded, was filled with notable examples.

- Wildfires in Canada consumed 18.5 million hectares, by far the country’s biggest fire season in the last four decades. In the runner-up year, only 7.1 million hectares burned. Smoke drifted across the continent, dulling the skies over Manhattan.

- Drought and low water levels in Gatun Lake prompted the Panama Canal Authority to severely restrict the number of ships that enter one of the world’s most important commercial waterways. In normal times about 36 per day transit the canal. By February, half that number will be allowed. The tightening has raised shipping costs and redirected global trade.

- In South America, Uruguay’s reservoirs shriveled and local authorities supplemented the capital’s dwindling drinking water supply with brackish water that exceeded health standards for salt. The Amazon River, also weakened by drought, dropped to a record low.

- In Libya, two large dams collapsed after severe rains in early September. The disaster, worsened by mismanagement, killed at least 4,000 people.

“Climate change is on track to exceed adaptive capacity in many parts of the world, particularly parts of the world where countries are already being hit hard and lack the resources to rebound or build greater resilience,” says Jonathan Overpeck of the University of Michigan. “Human-caused climate change, as well as the impacts of this change, appear to be accelerating, heightening the urgency for aggressive climate action.”

The causes of this Great Acceleration are not a mystery. A buildup of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere – due to burning fossil fuels, raising livestock, growing commodity crops, and clearing forests – is changing the world’s climate with severe consequences for water supply, ecosystems, and pollution.

In many ways, a new race has started. Can renewable energy accelerate at the same time that fossil fuel use and deforestation decelerate? Solar and wind power are growing apace, but from a small base. Fossil fuels still account for 80 percent of global energy use. Energy storage and electricity transmission will be needed to usher in the next phases of renewable growth.

A deteriorating climate is bad enough. But other decisions about where to build and how to use water are not helping. Bad policies and economic desperation – encouraging development in floodplains, for instance, or allowing unfettered extraction of water – make the situation worse. Vulnerability increases.

With advances in planetary monitoring and computer modeling, governments can no longer pretend that the future is unknowable.

Acknowledging the damage, governments are starting to change course. Water is one of the most common components of national climate adaptation plans. There is agreement that freshwater ecosystems need better care. One standout example: the world’s largest dam removal project is taking place in northern California and southern Oregon. Four large dams on the Klamath River are being demolished, a $450 million reclamation project to reopen salmon habitat that had been blocked for a century. The first dam was torn down this year.

Change will not come easily. Pledges are easy to sign but hard to implement. Institutions evolve slowly. Yet the consequences of delay – both in reducing carbon emissions and making water-smart decisions – are real. Just look at Acapulco. Fitch, a ratings agency, estimates economic losses from Hurricane Otis to be $16 billion. Livelihoods have been upended. Dozens of people died.

Leaders would do well to heed the advice of the National Hurricane Center forecasters, once they realized Otis was gathering catastrophic force.

“This is an extremely dangerous situation,” they wrote in a mid-day bulletin before the storm hit. “And all preparations for Otis should be rushed to completion.”

Toxic Terrain: Policy

The U.S. government wants a “climate-smart” farming system – one that cuts its greenhouse gas emissions, builds soil health, and is prepared for weather extremes. Congress set aside $19.5 billion in the Inflation Reduction Act, the government’s largest climate investment, for such projects.

Despite the enormous potential to transform one of the country’s biggest polluters, environmental groups worry that the approach will entrench incumbent firms and owners that befouled air, land, and water with fertilizers, manure, and pesticides. Widely touted developments like converting animal wastes into methane, if not managed wisely, could result in waters polluted with the nutrient-rich byproduct.

In the Toxic Terrain project, senior editor Keith Schneider explores the policies, incentives, and outdated thinking that contribute to agriculture’s contamination of water in the Midwest states.

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/IMG_1450-2.jpg

1601

2400

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2023-08-30 13:15:192023-12-04 15:57:12Offering Up Advice For Farmers, Universities Add To US Water Pollution

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/IMG_1450-2.jpg

1601

2400

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2023-08-30 13:15:192023-12-04 15:57:12Offering Up Advice For Farmers, Universities Add To US Water Pollution

How Big Ag Pollutes America’s Waters and Makes Money Doing It

U.S. Pushes Farmers to Develop A New Crop: Energy

U.S. Counts on “Climate-Smart” Farms to Slow Global Warming

New U.S. Climate Law Will Make Water Contamination Worse

Toxic Terrain: Health

The water-related health risks of life in farm country are attracting more scrutiny. The same chemicals that nurtured eye-popping grain yields and world-beating land productivity are making people sick.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency restarted a human health assessment of nitrate in drinking water and food. The agency had suspended the assessment during the Trump administration. The revival came at the request of three EPA divisions: Office of Water, Region 5, and Office of Children’s Health Protection.

Leaders in those units have noticed the rising number of studies linking exposure to nitrate and other farm chemicals to an array of health problems: adult and childhood cancers and babies born prematurely or underweight.

Acknowledging the risks to private well owners, whose water is not regulated, the EPA ordered Minnesota regulators to provide alternative water supplies to households in three counties in the state’s southeastern region. The EPA also directed Minnesota regulators to develop a long-term plan to reduce nitrate contamination of drinking water.

US Regulators Order Minnesota to Clean Up Nitrate Contaminated Water

EPA Restarts Assessment of Health Risks from Nitrate in Water

“What We’re Up Against” – North Dakota Towns Fight Farm Bureau to Keep Water Clean

In Minnesota, Families Blame Farm Nutrient Contamination On Heavy Cancer Toll

In Iowa, a Tale of Politics, Power, and Contaminated Water

Water in the American West

On the cusp of water calamity 12 months ago, the western states were granted a temporary reprieve from truly difficult decisions.

Last December, California’s second largest reservoir was near a record low, just a quarter full. By the start of summer, after months of drenching rains, Lake Oroville was at the brim. Along the Colorado River, a wet winter lifted reservoirs out of the immediate danger zone. The unexpected inflows – and billions in public funding for farm conservation – eased pressure while the basin’s seven states began negotiating new rules to manage an ebbing supply.

Bountiful moisture, however, was not unequivocally a blessing. Storm after storm arose in the Pacific and bashed into California. These sodden atmospheric rivers broke levees, flooded towns in the San Joaquin and Salinas valleys, and led to the rebirth of Tulare Lake, once the largest lake west of the Mississippi, until it was drained a century ago for agriculture.

States took steps to preserve water in times of need. Arizona declared that groundwater reserves around the fast-growing exurb of Buckeye are insufficient to supply the tens of thousands of homes developers have planned for the area. California warned six local management agencies that their groundwater protection plans are inadequate. And Nevada passed a law allowing the Las Vegas water supplier to limit household water use when Lake Mead, its water source, is low.

Billions in Federal Assistance after New Mexico’s Largest Wildfire. But Little Money to Repair Streams

New Mexico’s Largest Fire Wrecked This City’s Water Source

Social Media Used To Warn of Flood Dangers in Northern California

Say Goodbye to Lawns in Drying U.S. West

Tax Incentives Find New Purpose for Conserving Water in American West

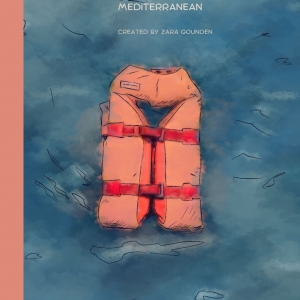

Water Migrants

Libya has become a teeming hub for migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean to claim asylum in Europe. They flee their home countries for a number of reasons – water insecurity, flooding, conflict, work. And they arrive in Libya already fatigued from journeys that began in Bangladesh, Pakistan, or Egypt. But for all, the grasp for life is full of peril.

Circle of Blue interns Zara Gounden and Fraser Byers explained the causes and witnessed daring rescues in the Mediterranean aboard the M.V. Geobarents, a search and rescue vessel operated by Medecins Sans Frontieres.

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/1.jpg

2000

1414

Zara Gounden

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Zara Gounden2023-10-05 15:41:112023-12-04 17:07:18Water Migrants: Rising Death Toll in the Mediterranean

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/1.jpg

2000

1414

Zara Gounden

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Zara Gounden2023-10-05 15:41:112023-12-04 17:07:18Water Migrants: Rising Death Toll in the Mediterranean https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2023-08-MSF-Mediterranean-Fbyers-P1110547-Edit-2500.jpg

1200

1600

Zara Gounden

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Zara Gounden2023-09-12 14:37:382023-12-04 17:06:43Water Migrants: Reaching European Shores

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/2023-08-MSF-Mediterranean-Fbyers-P1110547-Edit-2500.jpg

1200

1600

Zara Gounden

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Zara Gounden2023-09-12 14:37:382023-12-04 17:06:43Water Migrants: Reaching European Shores https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Screenshot-2023-08-22-at-2.48.19-PM.png

1376

1882

Fraser Byers

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Fraser Byers2023-08-23 11:19:192023-12-04 17:06:32Water Migrants: Crisis in the Mediterranean Episode 2

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Screenshot-2023-08-22-at-2.48.19-PM.png

1376

1882

Fraser Byers

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Fraser Byers2023-08-23 11:19:192023-12-04 17:06:32Water Migrants: Crisis in the Mediterranean Episode 2

Streams of Migration – Special Frontline Report

Great Lakes Water Quality

Fifty years after the Clean Water Act, water quality in the Great Lakes region faces new threats and familiar challenges.

Non-native plants and fish. Rising chloride levels in groundwater and streams due to spreading salt on roads in the winter. Pollutants flushed from farm fields that fuel harmful algal blooms. Wetlands in various states of protection after the U.S. Supreme Court’s Sackett decision, which limited federal oversight.

In this environment new actors are stepping up. Tribes are asserting their sovereignty and working to restore wild rice while also setting their own water quality standards to guard against pollutants from big farms and mines.

Oil pipelines remain a flash point in the region. Michigan regulators recently approved Enbridge’s plan to build a tunnel beneath the Straits of Mackinac to house its Line 5 oil pipeline. Federal approval still needs to be secured. Earlier in the year, a federal judge gave Enbridge three years to shut down a segment of Line 5 in Wisconsin that crosses the lands of the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

Clock Ticks for Water Utilities to Join National PFAS Settlements

Control for Frog-bit and Water Soldiers

Michigan Tribes Fight Long Odds to Restore Wild Rice, Their History

Bubbles and Electricity Designed to Deter Invasive Carp From Lake Michigan

Road Salt, A Stealthy Pollutant, Is Damaging Michigan Waters

Great Lakes Water Quantity

Abundant water is not guaranteed, even in a region defined by some of the world’s largest freshwater lakes.

That’s true for cities like Joliet, Illinois, which extracted too much water from its aquifers and will switch to Lake Michigan as its water source. And for Highland Park, an impoverished former auto hub nested within Detroit. State lawmakers brokered a deal to upgrade Highland Park’s aging water infrastructure and end a long-running regional dispute over the city’s unpaid water bills.

Chicago Suburbs, Running Out of Water, Will Tap Lake Michigan

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/2016-04-Michigan-Infrastructure-TVC-JCGanter_4987-2500.jpg

1067

1600

Vladislava Sukhanovskaya

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Vladislava Sukhanovskaya2023-08-18 11:27:352023-12-04 19:32:25Illinois is Losing Water

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/2016-04-Michigan-Infrastructure-TVC-JCGanter_4987-2500.jpg

1067

1600

Vladislava Sukhanovskaya

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Vladislava Sukhanovskaya2023-08-18 11:27:352023-12-04 19:32:25Illinois is Losing Water

Minnesota Tribe Sets Enforceable Rules To Safeguard Wild Rice and Water Supply

Forest to MI Faucet: Using Trees to Keep Water Sources Pristine

Great Lakes Take Global Stage

U.S. Water Infrastructure

Two years after the landmark Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act put $50 billion toward water system renewal, money is flowing to projects that remove lead pipes, recycle water, and replace leaky water mains. Billions more in taxpayer dollars are being invested in drought resilience.

Despite the once-in-a-generation federal outlay, the needs are still greater – and growing.

The Biden administration is proposing a 10-year deadline to remove most of the country’s roughly 9 million lead pipes. That alone could cost as much as $60 billion. Add to that first-ever federal rules on PFAS in drinking water, which the EPA aims to finalize by the end of the year, and costs to utilities and their customers will rise further.

Cities still invested in projects to improve water quality and reliability. DC Water completed the final segment of a 12-mile tunnel system that is designed to dramatically reduce sewage overflows into the Anacostia River.

Workers Needed to Fulfill America’s Infrastructure Goals

Louisiana Becomes First State to Issue Drinking Water Report Cards

Ongoing Battle to Keep Toxic Chemicals at Bay

Flush with Cash, State Lawmakers Consider Water Risks

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2022-01-Arizona-KSchneider-IMG_7497-Edit-2500-1-1.jpg

1067

1600

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2023-01-06 10:18:422023-12-05 11:28:4520 Years of Severe Drought Impede Huge Developments in Southwest

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/2022-01-Arizona-KSchneider-IMG_7497-Edit-2500-1-1.jpg

1067

1600

Keith Schneider

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Keith Schneider2023-01-06 10:18:422023-12-05 11:28:4520 Years of Severe Drought Impede Huge Developments in SouthwestWorld’s Growing Water Risks

Water leaders gathered in Manhattan in March for the United Nations’ first water conference in nearly five decades. There was plenty to discuss, including a report from the Global Commission on the Economics of Water that outlined a seven-point action plan.

In most basic terms, rising temperatures are raising the stakes for water. A fifth consecutive subpar rainy season buckled the Horn of Africa. The Amazon River reached a historic low. And China was beset by a year of heat records and floods.

In the face of these climate shocks, leaders, policymakers, and funders are beginning to realize that water should be a focal point in adapting to an unstable environment. These commitments are being addressed in national climate plans submitted under the Paris Agreement. A November 2023 assessment found that top priorities for countries in these plans are water, food, wetlands, and human health.

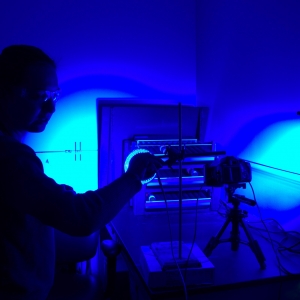

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/o2-dark-room.jpg

1602

2400

Circle Blue

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Circle Blue2023-07-25 15:38:362023-12-05 11:44:45Exploring Rivers Around the Globe for Clues to Carbon and Climate Change

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/o2-dark-room.jpg

1602

2400

Circle Blue

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Circle Blue2023-07-25 15:38:362023-12-05 11:44:45Exploring Rivers Around the Globe for Clues to Carbon and Climate Change

Cholera Cases Spike Amid Extreme Weather, Conflict

UN Water Conference Marked by Enthusiasm, Uncertainty

Majority Say Water Supply and Pollution ‘Very Serious’ Problems

As Planet Warms, Water Risks Abound

HotSpots H2O

Conflicts involving water continue to flare.

Researchers at the Pacific Institute, an organization that tracks this trend, updated their database, adding 345 water-related conflicts in 2022 and the first half of 2023.

Though herder-farmer conflicts fester in the Sahel and Horn of Africa, two major developments this year will add to the tally: Russia’s ongoing invasion of Ukraine and the war Israel is waging in Gaza against Hamas.

Water, in both cases, is being leveraged as a weapon and is a casualty of the conflict.

Russian forces targeted dams in Ukraine, while in Gaza drinking water is scarce and sewage runs freely due to Israel’s bombardment and fuel blockade.

The World Health Organization warns of a health crisis in Gaza, where cholera and hepatitis are now spreading. Gazans have abandoned the north, where fighting is most intense, and fled south. A crowded population without adequate water, sewage treatment, food, and health care is another sort of hot spot – one of disease.

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Gaza-Strip-October-2023.jpeg

1066

1599

Fraser Byers

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Fraser Byers2023-10-17 16:48:292023-12-05 21:54:48Hotspots H20: Israel Pledges to Resume Gaza Water Deliveries

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/Gaza-Strip-October-2023.jpeg

1066

1599

Fraser Byers

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Fraser Byers2023-10-17 16:48:292023-12-05 21:54:48Hotspots H20: Israel Pledges to Resume Gaza Water Deliveries https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/5334884484_8f487035b9_k.jpg

1074

1600

Fraser Byers

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Fraser Byers2023-07-12 16:47:072023-12-05 21:54:43HOTSPOTS H20: Drought Restrictions Hamper Big Ships Crossing Panama Canal

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/5334884484_8f487035b9_k.jpg

1074

1600

Fraser Byers

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Fraser Byers2023-07-12 16:47:072023-12-05 21:54:43HOTSPOTS H20: Drought Restrictions Hamper Big Ships Crossing Panama Canal https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Saint-soline-image.jpeg

1200

1600

Fraser Byers

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Fraser Byers2023-06-21 10:46:532023-12-05 21:54:13HOTSPOTS H2O: UN Condemns Violence Against French Water Defenders

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Saint-soline-image.jpeg

1200

1600

Fraser Byers

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Fraser Byers2023-06-21 10:46:532023-12-05 21:54:13HOTSPOTS H2O: UN Condemns Violence Against French Water Defenders https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/52064549919_783e986f94_k.jpg

1066

1600

Circle Blue

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Circle Blue2023-06-07 09:27:142023-12-05 21:54:33HOTSPOTS H2O: Day Zero Threatens Uruguay’s Capital

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/52064549919_783e986f94_k.jpg

1066

1600

Circle Blue

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Circle Blue2023-06-07 09:27:142023-12-05 21:54:33HOTSPOTS H2O: Day Zero Threatens Uruguay’s Capital https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/20221905_NYU_Clean-Water-and-Sanitation-at-the-Heart-of-Europes-Migrant-Crisis_photo1-2.png

900

1600

Circle Blue

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Circle Blue2023-05-31 16:31:422023-12-06 09:41:18HOTSPOTS H2O: Failing Rains in Darfur Foster Conflict and Displacement

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/20221905_NYU_Clean-Water-and-Sanitation-at-the-Heart-of-Europes-Migrant-Crisis_photo1-2.png

900

1600

Circle Blue

https://www.circleofblue.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Circle-of-Blue-Water-Speaks-600x139.png

Circle Blue2023-05-31 16:31:422023-12-06 09:41:18HOTSPOTS H2O: Failing Rains in Darfur Foster Conflict and DisplacementCorrection: An earlier version of this story said that 18.5 million acres burned in Canada. It was 18.5 million hectares.

Images:

Chicago © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

Brian Bennerotte © Keith Schneider/Circle of Blue

Grain harvest © Keith Schneider/Circle of Blue

Hermit’s Peak © Brett Walton/Circle of Blue

Mediterranean Sea migrants © Fraser Byers/Circle of Blue

Lovells marsh, Michigan © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

Chicago skyline © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

Water line replacement © J. Carl Ganter/Circle of Blue

Derna, Libya © UNICEF/UNI437442/Alatrib

Related

© 2025 Circle of Blue – all rights reserved

Terms of Service | Privacy Policy