Divining Destiny: Water Challenges in Mexico’s Tehuacán Valley

On March 20, 2006 during the Fourth World Water Forum in Mexico City, Circle of Blue premiered “Tehuacán: Divining Destiny,” a pivotal, comprehensive multimedia report that focused the world’s attention on one community’s struggle with water scarcity, pollution and climate change. It was reported in multiple dimensions by Newsweek’s Latin America bureau chief Joe Contreras, World Press-winning Getty photojournalist Brent Stirton, and Circle of Blue’s multimedia team.

It’s a one-mile walk to the stream where this mother bathes her children twice a week. Photos © Brent Stirton / Reportage by Getty Images for Circle of Blue

By Joe Contreras, Special to Circle of Blue

By the standards of rural Mexico, Francisca Rosas Valencia cuts an unlikely figure as community leaders go. The 46-year-old mother of nine has spent her entire life in San Marcos Tlacoyalco, a dusty town of 10,000 people located in the heart of the Tehuacán Valley southeast of Mexico City, and decision-making is not among the roles generally assigned to women in her indigenous Popoloca ethnic group.

Demand for Mexico’s finite supply of water will rise steadily for the foreseeable future. Demographers predict that the country’s population will surpass 120 million by the year 2025, yet as of 2001 the nation’s Environment Minister reported that 12 million Mexicans had no access to safe drinking water. As in many other nations, Mexico’s existing supplies of water are unevenly distributed. The arid northern third of the country is home to only nine per cent of Mexico’s total volume of river water, whereas the southern states that account for about 20 per cent of the national territory boast the best aquifers, have fully half of the river water supply and receive most of the rainfall nationwide.

The traditional admonishment to foreigners freshly arrived in Mexico against drinking the water is no glib cliché. Only two per cent of the nation’s surface water is classified as being of high quality, and a United Nations survey that evaluated water quality in 122 countries placed Mexico near the bottom of the list at number 106, behind the likes of Guatemala, Egypt and China. Contaminated water ranks second among causes of infant mortality nationwide, and untreated wastewater from homes and industries ranks as the main culprit.

Polluted water is a grim fact of life for both city dwellers and rural villagers. In 1996 the government-run National Water Commission reported high concentrations of toxic chemicals in wells used by the industrial city of León for drinking water. An estimated 150,000 residents of Mexico City imbibe water with dangerously high levels of arsenic. The public health hazards associated with contaminated water supplies aren’t confined to any single region of the country: so-called “black waters” have been used to grow vegetables near the southern city of San Cristóbal de las Casas and alfalfa and other forage crops in the central Mexican state of Querétaro.

The country’s agribusiness sector is a leading source of water pollution. About 6,000 residents of the Mexican capital consume water containing harmful amounts of pesticide. According to the National Water Commission, wastewater from 61 sugar mills generated 6.2 tons of biochemical oxygen demand in 2000, a reliable yardstick of the amount of fecal and other organic material in water. Pig farms in particular generate massive quantities of excrement that foul rural water supplies. The risks arising from polluted water in the countryside threaten wildlife as well as human beings: over 8,000 migratory birds died near the town of Tequisquiapan after drinking from contaminated ponds and streams.

Aging infrastructure is aggravating the country’s shortage of safe water. The amount of water lost daily from ruptured pipes in Mexico City is large enough to supply a metropolis the size of Rome. The rapid pace of urbanization throughout the country further taxes the nation’s water supply. Over 20 million people live in the Mexican capital and its outlying suburbs, and the prohibitively high cost of building new water treatment plants has led municipal officials to draw an ever-growing percentage of the capital’s water supply from surrounding rural areas.

A lone Mexican woman skirts a jaguey near San Marcos Tlacoyalco. These man-made, earth-bermed basins collect rainwater for livestock and also supply water for domestic needs. Photos © Brent Stirton / Reportage by Getty Images for Circle of Blue

Successive governments at the national level have recognized the urgent issues at stake with water. Mexico became the first Western country to create a cabinet-level ministry charged with managing water supply when it established the Ministry of Hydraulic Resources in 1947. President Vicente Fox has identified water as a national security issue for Mexico and supported reforms that were incorporated in a major amendment to the National Water Law in 2004. Those reforms were designed to attract private investment in new and existing infrastructure and promote the privatization of drinking water systems in major cities.

At times, Mexican officials have tackled water-related health emergencies with impressive results. An outbreak of cholera in 1995 made headlines and elicited a concerted response from government health authorities: from a peak of 16,430 cases and 142 deaths reported in that year, the incidence of the disease fell sharply over the next five years until Mexico had become cholera-free by 2002. The country has also made impressive strides in recent years in expanding its potable water system and improving the quality of water furnished to millions of its citizens.

But more often than not, Mexico’s elected leaders have lacked the political will to enforce the existing body of laws designed to protect the environment. The federal government agency in charge of enforcing those laws slaps hundreds of companies with fines each month for assorted violations. But few of those firms pay much heed to the toothless agency: during the first six months of 2003, only 737 of the nearly 5,000 companies that were cited for environmental violations actually paid their fines.

The magnitude of the task at hand is daunting and will require a massive outlay of money and resources from the Mexican government. In 2001 the National Water Commission called for $77 billion in new federal government funding over the ensuing two decades to build new treatment plants to increase the supply of water suitable for human consumption and agricultural irrigation. Otherwise, some experts caution, the availability of water to Mexicans by the year 2025 could fall to levels regarded as dangerously low by the World Bank.

The national water crisis facing Mexico acquires a special poignancy in the context of the Tehuacán Valley. In modern times, the city of 250,000 that bears its name is best known for the mineral water drawn from local springs. To this day, a Mexican diner who wants to order a bottle of effervescent mineral water with his meal will ask a waiter for “un Tehuacán.” But the 775-square mile (2,000-square kilometer) valley that occupies the southeastern corner of Puebla state and a northern tip of Oaxaca state also holds a special place in the pre-Columbian history of Mexico. It marks the site where indigenous peoples domesticated corn as an agricultural crop for the first time in the history of mankind between the years 5000 and 3400 B.C. These farming pioneers also learned to cultivate beans, chilies, amaranth and marmalade trees, but the valley retains its fame as the worldwide cradle of maize.

Equally important, the Tehuacán Valley also witnessed another revolutionary development in the agricultural history of Mexico. In 750 B.C. the first dam in the region encompassing Mexico and Central America was built at a site near the present-day town of Coxcatlan by some of Francisca Rosas’ Popoloca ancestors. Estimated to have been 18 meters high, 400 meters long and 100 meters wide, the earthen dam enabled those early farmers to capture and store rainwater for subsequent irrigation of their crops. That momentous breakthrough marked a crucial contribution to what the scholars Scott Whiteford and Roberto Melville have called “the rich treasury of indigenous knowledge about the environment, food, plants and water management techniques.” From then onwards, native farmers could save up rainfall for use during the dry season to water their animals, irrigate their fields and slake their own thirst.

But nearly three millennia later, the descendants of those enterprising indigenous communities find their traditional way of life under siege. When President Carlos Salinas de Gortari embraced globalization and joined the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, the Mexican government set about dismantling the elaborate system of agricultural subsidies that had been established over the preceding 60 years to protect the nation’s farmers against foreign competition. Among the programs earmarked for reduction or elimination were subsidies for irrigation water–and as control over water resources was progressively decentralized, Mexico’s small farmers were left largely to fend for themselves.

Rosalino Carrasco Luna, 74, of Atecoxco is a corn farmer who says he has developed a water divining method using nothing but a rock dangling from a thin rope. He attributes the faltering rains of recent years to the alignment of certain planets. Photos © Brent Stirton / Reportage by Getty Images for Circle of Blue

The gradual lowering of tariff barriers to cheap U.S. food imports under NAFTA has devastated the nation’s agricultural sector, where nearly one-fifth of the country’s labor force was employed at the time the trade treaty took effect. Between 1994 and 2003, an estimated 1.3 million jobs in Mexican agriculture were eliminated, according to a report issued by the Washington-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. The fallout from NAFTA has been especially harsh on corn farmers, whose crops account for roughly 60 per cent of the nation’s arable land. During the three years prior to the dawn of the NAFTA era, Mexico was importing about a million tons of maize annually. By 2001, that figure had soared to over six million tons as Mexican corn flour producers increasingly preferred to buy their maize supply from Iowa instead of local sources.

The direct impact of NAFTA on the subsistence farmers of the Tehuacán Valley has been somewhat mitigated by the fact that they almost never raise enough corn to sell as a cash crop. In a good year, the campesinos of Santa Ana Teloxtoc will only produce enough maize to meet their own nutritional needs for six months, and some of them actually look forward to the day when a flood of U.S. corn imports might drive down the price of maize they must buy to supplement their own harvests. But the havoc wrought by NAFTA on the Mexican countryside in general has cast a pall on the economic prospects of the country’s small farmers and their families. For a young Mexican like Gregorio Juárez Gordillo, it is easier to find work on the farms of Virginia, where he once harvested tomatoes for a year, than it is in his hometown of San José Buenavista. Sitting astride his bicycle on a scorching weekday afternoon, the 32-year-old Juárez said he had also ventured to the southern state of Chiapas and Ciudad Juárez on the Mexican border across from El Paso in search of employment. He would soon be leaving the valley that gave birth to Mexican agriculture to meet up with an older brother already living in Mexico City. “It’s hard on my parents when I’m not with them, but we don’t have wells to irrigate the crops,” he shrugged. “There’s very little work here, and what there is pays poorly.”

The view from the hilltop hamlet of Paredones is especially bleak. Most of its 70 inhabitants are related to each other in one form or another, and the community’s lone source of water is a tiny reservoir at the foot of a rugged, cactus-covered hillside where groundwater collects year Ôround. Residents must trudge down to the reservoir each morning and fill up a pair of 20-liter plastic containers that are hauled back up to the village by mule. There is no water left over to irrigate the cornfields of Paredones, and the unusually low amounts of rainfall in 2005 made it one of the worst harvests in living memory. The plight of Paredones is particularly galling to Eloy Hernández Llanos, a 36-year-old father of three who worked in a car wash in Stamford, Connecticut for two years until he returned home in 2004. He can only shake his head when he recalls how a resource in such desperately short supply in Paredones could be used in profligate volumes to hose down luxury sedans and sport utility vehicles. “More than anything, it makes me angry that here there is so little water and there is so much over there,” says Hernández. “Many people [in the U.S.] waste water, they throw it away without recycling it to produce something or irrigate something. It could be put to so much better use here.”

“Government officials just believe in drilling, piping and pumping. We recycle ancient techniques but we can do that with modern engineering and materials.”

The conditions in Paredones are about as bad as they get in the Tehuacán Valley. Other towns and villages in the region are devising innovative ways to alleviate their chronic scarcity of water. Dozens of rural communities have received funding and technical assistance from Alternativas, the locally-based NGO that helped Francisca Rosas organize many of her neighbors into an amaranth farming cooperative. Since its inception in 1980, the organization has implemented over 1,500 water resource projects in the valley, ranging from the construction of stone terraces and dams to retain rainwater and halt land erosion to the installation of household waste treatment plants.

Alternativas has placed a special emphasis on using customs, technology and agricultural know-how that predate the modern era to better manage the region’s limited water resources. “Government officials just believe in drilling, piping and pumping,” notes the Alternativas Director General Raœl Hernández Garciadiego. “ We recycle ancient techniques but we can do that with modern engineering and materials.” Under the auspices of a program called Water Forever, the NGO has encouraged the use of underground horizontal wells known as galerias filtrantes that were introduced by Spanish authorities during the colonial era. The wells are upwardly inclined tunnels that use gravity to tap into groundwater located at higher elevations and bring it to the surface at a lower point in the valley. Believed to have originated in Persia around 1500 B.C., the galerias have proliferated in the Tehuacán Valley in recent decades and currently number around 500. “When our grandfathers passed away, this galeria was abandoned for about thirty years,” explains Pedro Hernández Martinez, an elderly campesino in the town of San Pedro Tetitlan, an indigenous term meaning “the place where stones abound.” “There was a substantial rainfall about four or five years ago and the community came together to discuss how they needed to clean out the galeria so that it would function again. This water equals life for our people, and for this reason we are working to maintain it.” Hydrological engineers also urge farming communities to ensure proper upkeep of jagueyes, ponds used to water livestock that often occupy a central location in the villages of the valley.

Alternativas also promotes the merchandising of snacks, candies and cookies made from amaranth, the small, protein-rich grain which was cultivated in the valley long before the arrival of the Conquistadores. Spanish authorities prohibited the cultivation of amaranth because it was blended with the blood of human and animal victims during indigenous sacrifice rituals. Anyone caught defying the ban risked amputation of his right hand. Despite such grisly antecedents, however, amaranth has been embraced by hundreds of peasant families who have reaped financial benefit from the marketing of amaranth products under the brand name Quali.

Rural residents of the mountain range known as the Mixteca are experimenting with new uses of water to improve the quality of their lives. The water used by Victoria Salas Ortiz to wash her family’s clothing is recycled to irrigate a lush flower garden in the front yard of her thatch-roofed hut. Like Francisca Rosas, Victoria is a Popoloca woman who wears her gray-streaked black hair in a braided ponytail and has endured more than her fair share of adversity. The father of Victoria’s 11 children died from cancer at the age of 53, and a teenaged son was killed by a passing motorist as he rode his bike to school. Salas inherited her love of flowers from her mother, and the white lilies and the pink blossoms of Victoria’s regina trees serve to brighten her otherwise humdrum existence as a hat weaver in the village of Estanzuela. “When I used to visit the town of San Pedro Atzumba I would see the gardens of the women living there and say to myself, ÔOh, how I would like to have my own garden,’” recalls Salas. “In past years we never had enough water but now, thank God, we get water pumped to the house every eight days and it lasts us for five.”

Farmers in the town of Santa Ana Teloxtoc are seeing for themselves the tangible benefits that drip irrigation can bring to their crops. A small parcel of land measuring 25 meters by 25 meters in the middle of town has been fitted with rubber hoses that water neatly arranged rows of plants for 30-minute periods two or three times a week. The demonstration plot was planted with corn, beans, peas, cantaloupe, wheat and squash in December of last year, and many of Santa Ana’s 3,000 residents have been favorably impressed by how well the crops are responding to the drip irrigation technology.“ One young guy with a small tomato garden is using this system,” noted Valent’n Carrillo Hernández, one of the town elders in his mid-70s. “He’s already beginning to see results.”

San Marcos Tlacoyalco. This couple has been fetching water from the same place for 50 years. This takes such a significant portion of their day that they have time for little else. Photos © Brent Stirton / Reportage by Getty Images for Circle of Blue

Yet for all the good works being carried out under the supervision of Alternativas in the Tehuacán Valley and its environs, there is a nagging sense of a losing battle that is being waged. The human exodus shows no signs of slowing any time soon: more than 100 residents of Santa Ana have voted with their feet in recent years, and three of Valent’n Carrillo’s nephews have started new lives in New York. “We have created sounder bases of livelihood for people who have chosen to stay behind,” says Alternativas chief Raul Hernández Garciadiego. “But we have not stopped immigration.” He characterizes the region’s lack of water as the “axis problem” around which all of the local economy’s deficiencies revolve.

There is widespread agreement that rainfall patterns in the area have been on the decline for some time. Good rains have not graced the region since 2003, and theories abound among local farmers as to the causes behind the phenomenon. Valent’n Carrillo’s son Edilberto asked me with a straight face whether I had heard rumors that the wealthy owner of a large chicken farm in the vicinity of Santa Ana had hired crop duster planes to spray clouds with a rain-inhibiting gas.

A grizzled corn farmer in the town of Atecoxco named Rosalino Carrasco Luna volunteered the most outlandish explanation of all. Over the course of his 75 years, Carrasco said he had developed a water divining technique involving the use of a stone tied with a piece of rope that he dangled above the surface of his farmland. If the stone moved at any time, he explained, there was bound to be water below the spot where he was standing. He attributed the faltering rains of recent years to the positioning of certain planets in the solar system. “It has to do with the stars and Jupiter and Venus,” the balding peasant said with conviction. “When one of those planets is in front of the sun and the other is behind it, outer space heats up and the rain falls only on the coastal plains.”

Whatever the real causes behind the vanishing rains, the meteorological trend poses a serious threat to the Tehuacán Valley’s future water supply. The northern portion of the valley relies on the Tecamachalco aquifer for its groundwater, and in 2004 the volume of water registered a net drop of 93 million cubic meters as the rate of extraction outstripped the rate at which the aquifer was replenished by precipitation. The proliferation of deep wells in the area has placed a heavy burden on the aquifer, and a large number of these wells service major agribusiness operations at the expense of small farmers.

Uncertainty about future supplies of safe water is not limited to the indigent small farmers of the valley. It is also a source of growing concern for the residents of the city of Tehuacán. The second largest city in the central state of Puebla has seen its population nearly double in the past 15 years, and as with so many other cities in Mexico and elsewhere in Latin America, the urban sprawl has largely occurred in the absence of proper zoning and infrastructure improvements to keep pace with a mushrooming population. A recent article in the local newspaper El Mundo reported that municipal officials needed to provide an additional 17.2 million liters of water per day to meet the expanding needs of its inhabitants. The head of the city’s potable water and sewage services said a new well would be drilled in the coming weeks to compensate for the current shortfall in water supply, a band-aid solution that will place yet more demands on the region’s already declining aquifer. There was a time in the city’s not so distant past when groundwater could be found at a depth of 15 meters. By 2002, however, wells had to be dug at least as deep as 200 meters.

In the early 1990s, Tehuacán city acquired the dubious distinction of ranking among the ten most polluted metropolitan centers in the country. Some Tehuacáneros walk the streets of the city’s bustling downtown with blue surgical masks to ward off the dust and fecal matter floating in the air. And in recent years, the city’s environmental woes have been compounded by the pollution from industrial-scale laundries that wash jeans for garment assembly plants known as maquiladoras.

“It costs 15,000 pesos a day to operate those water treatment plants, so they are only turned on when a government inspector or a representative from Levi’s or The Gap is planning a visit.”

With the active support of the Mexican government, U.S. companies began establishing maquiladoras on the Mexican side of the border in the 1960s to produce apparel, electronic appliances, auto parts and other manufactured goods fashioned from raw materials and components that had been imported from the U.S. The incentives were pretty straightforward: take advantage of the low wages, generous tax incentives and weak labor and environmental regulations prevailing in Mexico to produce finished products at a fraction of the cost incurred at a manufacturing facility north of the border. Spurred by the signing of the NAFTA treaty, new maquiladoras dedicated to the production of blue jeans began opening their doors in Tehuacán in the mid-1990s. Before long, many of the best-known jeans companies like Guess, Levi’s and Gap were getting large numbers of their trousers from plants located in Tehuacán, and the city’s booming maquiladora sector created thousands of new jobs for the region.

The rise of jeans-producing maquiladoras has exacted a significant toll on the surrounding environment. The dyes used in the manufacturing process contain significant amounts of toxic chemicals, and the popularity of the “stone-washed” look requires the application of enzymes in the laundries to give the trousers a faded appearance and a softer feel. In the process, says the Toronto-based Maquila Solidarity Network organization, the maquiladoras’ low-paid Mexican workers are exposed to a variety of harmful substances ranging from caustic soda and chlorine to peroxide and oxalic acid. And that’s not all. “Chemicals used in the laundries often end up polluting local waters,” charges the group at its website. “Mexico’s lax enforcement of environmental laws allows companies to dump dyes into surrounding bodies of water, polluting the groundwater that feeds nearby farms. The deep blue [color] of the creeks surrounding factories in Tehuacán is the dangerous result of such unregulated dumping.”

Stung by news media coverage of unfair labor practices on the assembly floor and pollution caused by the laundries, leading U.S. jeans companies pressured some of their larger Mexican suppliers to take remedial action at their maquiladoras. The Grupo Navarra firm installed water treatment plants at its jeans factories in Tehuacán six years ago and publicized the development at its website. The maquiladora boom in Tehuacán ended six years ago as some companies decided to move their foreign manufacturing operations to countries like China and Honduras with even lower wage scales than Mexico. As a result, the number of major laundries shrank from a peak of 25 in 2003 to just eight today.

But the pollution from the town’s remaining maquiladoras and associated laundries continues unabated, say community activists. Some of the bluish water is discharged into a large, open-air drain on the outskirts of the city and is eventually recycled to irrigate farmland downstream in the town of San Diego Chalma. “Everything is the same or even worse,” says Martin Barrios Hernández of the Tehuacán Valley Human and Labor Rights Commission. “It costs 15,000 pesos a day to operate those water treatment plants, so they are only turned on when a government inspector or a representative from Levi’s or The Gap is planning a visit. The city government does absolutely nothing to punish these maquiladoras, and the laundries are destroying the environment and exhausting the water supply.”

Barrios’ claims are corroborated by a prominent physician in the city. Rodolfo Celio Murillo is a pediatrician, specializing in the treatment of allergies, who grew up in Tehuacán when it was a mid-sized town of 40,000 people. In recent months, he has seen with his own eyes the telltale puddles of blue water that collect on the streets he drives down on his way home from work. “All of the laundries that are still here are discharging [dyes and chemicals],” says Celio. “Part of the problem has to do with the shortage of government inspectors to monitor the industry, part of it is corruption.” The 45-year-old doctor blames contaminated water in part for the unusually high incidence of diarrhea and certain skin diseases among city residents.

The Carrillo family constructed this water collection reservoir with the help of Alternativas, a regional nonprofit organization. Using a system of pipes and terraces, they are able to deliver precious water to their fields in the valley. Photos © Brent Stirton / Reportage by Getty Images for Circle of Blue

Health risks are one of the many water-related difficulties confronting Francisca Rosas. The steady exodus of young men and women like her son Florentino from the town of San Marcos Tlacoyalco raises troubling questions about the well-being of her grandchildren and the survival of Francisca’s Popoloca culture and language. “My life is on loan from God, and I wonder about the future that lies in store,” she admits.“ That is my uneasiness both as a person and as the mother of a family. At times we don’t have water for bathing, and that brings with it many health problems. I’m worried that in the long term we won’t have enough water.”

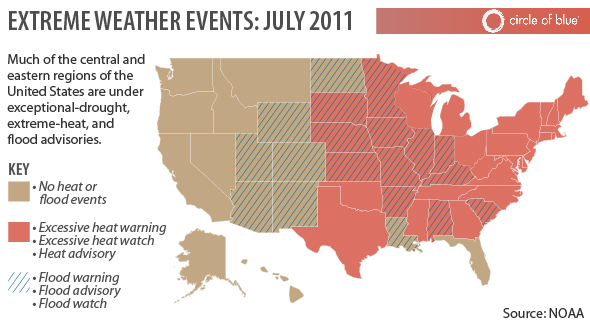

Her words are a warning that other societies ignore at their peril. Yet at the same time, Francisca’s efforts to help conserve the limited water supply in her hometown offer an example that governments should emulate if the world is to avert a catastrophe of biblical proportions. President Vicente Fox underscored the gravity of the many issues tied to mankind’s most indispensable resource in announcing that Mexico would be hosting the fourth World Water Forum in March 2006. “Water is the great theme of the 21st century,” declared Fox at a ceremony held at the presidential residence of Los Pinos. “It is our common future, [and] together the societies and governments of the world should take decisive action that will preserve and guarantee this natural treasure.” As Fox rightly noted, Mexico is not alone in facing tough policy decisions over the management of its water. Over a third of the world’s population face extreme water scarcity on a daily basis, and experts predict that chronic shortages will afflict significant portions of Africa, India, the Middle East and the western United States within the next decade.

As the personal accounts of farmers in the Tehuacán Valley have demonstrated, there is much to be learned from the successes and failures of Mexico in coping with the most pressing challenge facing the planet in the foreseeable future. “Our goal is to increase our water resources,” explains Armando Castillo Osorio, a diminutive farmer from San Pedro Tetitlan who often donates his own time to help maintain the galeria filtrante originally excavated by the town’s forefathers. “We have very little, but we work in the hope of providing more water for our people. I still feel proud that I am from San Pedro and that my people, our ancestors, have left us with something.”

Produced with support from the Ford Foundation.

While this report offers some limited information about two different worlds co-existing in current day Mexico, it is framed in such a way as to mislead the reader and confuse issues, motivations, people’s roles and the underlying causes. The problems start with minor errors like identifying the statement by Raul (NOT Reoel) Hernández as “General”, or more serious ones that suggest the inability of Mexico’s peasants to produce corn (In fact, the country is self-sufficient in white and colored corns required for human consumption; Nafta effectively made imports of US corn used for industrial proccesses and animal feed less expensive) — to not continue.

However, by jumping from the vignettes of Alternativas’ actions to the contamination and poor water management systems created by the political system, the author has done a terrible disservice to an understanding of the situation. Alternativas is a NGO model that has successfully stimulated the emergence of a complex industrial and cooperative system of production benefiting more than 100,000 people in more than 100 villages joined in a politically interesting model of alliances that merits explanation (I won’t do that here-I have done this elsewhere).

In contrast, the rest of the article describes a pattern of technical incompetence, lack of political will, corruption and, perhaps more tellingly for your audience, lack of capacity of the US-based “anti-sweatshop” campaign to actually obtain compliance with headquarters commitments of the transnational garment industry firms contracting with local politically important bosses in Mexico. To end this synthetic comment, I simply add that the problem that Mexico faces in this regard is not one of water shortage but rather of erroneous choices of technologies, misplaced priorities and a political model based on serving the interests of wealthy and powerful and assumptions that the people are the problem rather than the solution.