Overcoming the sanitation stigma: An interview with author Rose George

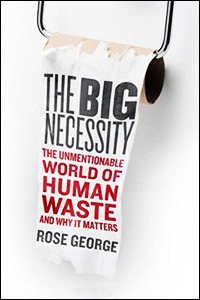

In an interview with Circle of Blue, freelance journalist and author Rose George explores the politics of sanitation. She discusses sanitation’s crucial but linguistically fickle role in social dialogue. George elaborates on the history of sanitation both above and below the equator, as well as touching on recent successes and failures. Her new book — The Big Necessity: The Unmentionable World of Human Waste and Why It Matters — examines the politics of defecation worldwide. Read the review.

Why sanitation and why now? Why do you think this is an important subject to have in the public discourse?

Well, it’s always been an important subject. It’s just that we’ve kind of forgotten about how important it is. Because ever since we’ve had the flush toilet, we’ve been able to press the flush and then forget about where the waste goes to. But one hundred and fifty years ago obviously with the cholera outbreaks in London and also in the States people were much more aware of the importance of sanitation and how crucial it is in the West, in the developed and the developing worlds.

The reason that it’s particularly important at the moment — not just at the moment but increasingly important — is that dreadful figure of 2.6 billion people without a toilet or any form of sanitation, which is obviously just a disgraceful figure. And a child dying of diarrhea every fifteen seconds — these are just really horrific statistics. But yet, when you look at other really bad public health issues like malaria or HIV they do get a lot of political attention and funding; whereas sanitation still is sort of the neglected orphan of the development world. [It’s] just not getting anything like the attention it needs. It doesn’t get any funding either, certainly not enough. And this is the international year of sanitation.

When it comes to funding and aid from Western countries, do you have any idea what the estimated aid is right now for sanitation related issues?

No, I don’t have the figure. I can look that up for you. But I do know it’s gone down. It’s gone down over the last ten years or so. But I can find the figure. It’s not just about aid though. It’s also about mental budgets. It’s a problem within government, but it’s within aid budgets too. If you know about fresh water you know that it’ll only get about one percent of the national budget anyway and most of that — 90 percent of that — will go on clean water and ten percent on sanitation, which just doesn’t make sense when you look at the public health benefits of sanitation. So a good latrine or some good form of containment can cut disease by 40 percent. Four, zero. Whereas clean water is 20 percent. The ideal is to have sanitation, water and hand washing; and then that’s 80 percent, which is pretty stunning.

What do you think is the biggest obstacle? What specific examples are there of things that are preventing it from happening in say India or parts of Africa?

I think there are a few things. Well, let’s take the aid world, the people who are giving money to these places–India and Africa. I think the big issue there is that there is a linguistic taboo. It’s not considered a polite subject of conversation. So, this sort of spreads across the board. So people, in terms of staffing and talent and stuff, the best people don’t want to work in sanitation; they want to work in water. It’s just got more cache.

So you have this difficulty of it just not being able to be talked about. There’s no neutral word for it anymore. There was two-hundred, three-hundred years ago, but we’ve now turned all our words related to bodily functions into our worst swear words. The rise of Puritanism has been responsible for that.

The other issue is — and this is true in governments and the aid world — sanitation is like a political football. No one department has responsibility for it, so it gets kicked around. So it’s going to be local government or it’s going to be health, or it’s going to be forestry and water affairs. And so you have this kind of fragmenting of attention and priorities. And it just ends up being looked after by nobody. I think at the moment 23 agencies in the UN have responsibility for sanitation. But there’s no UN Sanitation. There’s a UN Water, but there’s no UN Sanitation, despite the appalling battle associated with it.

The other difficulty is that what people are understanding now is that sanitation is quite complicated, because human beings are complicated. I’m sure you’ve seen this in East Africa. It’s not as easy. You can’t just put in the latrine and someone’s going to use it, someone who’s been doing open defecation for twenty years or for generations. So that’s what happened in India. All these nice government-subsidized latrines were practically given to people all over the country. And then you’d go back in a few years and find that they’d been turned into goat sheds or temples or rooms, because they were nicer than people’s houses. And the people who had been given the latrines were so used to going to the nearest bush that it was hard to change their habits. So now people are realizing that sanitation is also about human behavior and psychology. It’s more about working out the software rather than just providing the hardware.

In terms of India, for example, you are suggesting that there’s an educational issue with what they’re doing. Is the national government neglecting to provide the information required for the local populous to understand the importance of using the facilities?

Well, I think increasingly that the new trend in sanitation is the awareness that hygiene education is fundamental. You can’t just give someone a toilet and expect them to wash their hands properly. And so there is this awareness that maybe less money should be given on subsidizing extremely nice $300 latrines and maybe some of that money should be given to education, as you say.

And that is happening with this movement called CLTS (Community Led Total Sanitation), which I wrote about in the book. And that’s revolutionary. Principally, it does away with the concept of subsidy. That’s the ideal methodology, anyway. Subsidy is not important, whereas before it always was. And instead the idea is to trigger people to help themselves. So how they do that is they turn up in a village and have a tour of the village and then ask to be shown the open defecation grounds. Suddenly they’re standing in front of guests in front of a pile of shit, frankly. The idea is to trigger them into some sense of shame and disgust and then they will immediately dig latrines. And it seems to be working.

Then the other thing, on top of that, that’s being done in India — as well as the hygiene education — is this really interesting prize called the Nirmal Gram Puraskar clean village prize. So a village can qualify for a clean village prize if it declares itself to be 100 percent open defecation free. That’s a new acronym in India: ODF. So in the campaign for an ODF India, the prize is handed out and it gets lots of publicity. It’s handed out by the President. The idea is to encourage people’s pride as well, so it becomes kind of “cool” to become open defecation free. So that’s a really interesting development in India and Bangladesh and across Cambodia as well. Not so much in Africa so far, but it is being tried out in Africa.

Where does Community Led Total Sanitation function?

It started in Bangladesh. It’s very popular in India and Bangladesh. It’s big in Cambodia and Vietnam. It’s in lots and lots of countries, but at the moment it’s working best in Asia. But it has been tried out in Africa. I think Ethiopia, maybe Uganda as well. I think it’s having more difficulty in Africa. I’m not sure why. I think it’s something to do with some kind of fecal aversion. The disgusting isn’t working. I’m not sure. It’s having a few more teething problems in Africa, but it’s spread like wildfire in Asia. It’s got a lot of attention and funding. Some of it is being funded by the Gates Foundation and the World Bank. It’s the new fashion in sanitation.

Let’s talk a little bit about recycling human waste for other uses, like agriculture. Or using it as drinking water. How effective are programs in China, say, that turn human waste into agriculture byproducts or fuel?

Well, using human waste — which obviously means it shouldn’t be called waste — is actually much more common than we think. I mean in the States 70 percent of sewage sludge, which is the end product you get when you get the clean effluent. The solids that remain are called sewage sludge — although they’ve been re-baptized biosolids. Seventy percent of those are used on agricultural land in the States. And the same in the U.K.. China, though, has been using human waste for probably about 4,000 years, and there’s an argument that that’s why its agriculture is still thriving. Whereas other civilizations in the past have seen their soils dry out and be eroded and have failed as civilizations.

So China is very at home with its excrement and does see it as a resource rather than something just to be disposed of. When I was in China I visited a very good biogas program. They use a household biogas digester, an underground tank which digests human and animal waste in rural households. And you can take out the methane and use it as a cooking fuel. I saw these in place in rural villages in Szechuan and Gansu provinces in the center of China. And they seemed to be working very well.

There were some problems in the beginning, like 20 years ago, because again there wasn’t enough education to go along with the hardware. So they were clogging and failing. But now they seem to be working really well. Everyone I spoke to was absolutely delighted with it, because not only is it free cheap energy, apart from the cost of the digestor, it cuts down on deforestation. Women were spending hours every day going to cut down wood for fuel, causing great environmental problems in their region. And now they don’t have to, so they have more free time and they’re not cutting down the wood and they have free fuel. So it seems to be going great guns, but the question is whether that can be transferred to urban areas and in the West. I think it probably can, but it requires quite a lot of infrastructural renovation. But it is being tried out in Lille, in northern France. And they’ve got ten buses running on Biomethane; so it can be done.

In terms of the progress toward having better sanitation facilities, have there been any major set backs in the past 20 years that have really brought to light some issue that people didn’t realize there was an issue before? Have we seen any steps taken that have really failed — either as an aid program or as an implementation by a federal government for their own country?

Well, yea. There are failures all across the board. Anywhere you look, you’ll find a failed sanitation project. But I guess the one I know about is the India one I talked about. I mean India has been pouring money into sanitation for at least 20 years. Gandhi was talking about sanitation in 1949. He was always talking about sanitation and how they had to reduce open defecation and sort out the untouchables, who are untouchable because one of their jobs is to clean manual latrines with their bare hands.

But India has thrown money at this problem and it’s still going on for the reasons I’ve talked about earlier. But that said, I think one of the things that interests me, which came of my research, is that what we think of as the perfect solution, which is the Western model of sanitation — which is the wrong treatment — that’s certainly not perfect and it’s failing. One of the big setbacks was in Milwaukee in 1993 when Cryptosperidian got into the drinking water because it was in sewage. In certain areas sewage effluent is discharged into the same water course as drinking water is taken from. As it was Lake Michigan, 100 people died. So that was clearly a setback and a sign that maybe water-borne wastewater treatment could do with some tinkering with.

And also every week in the States you get raw sewage being discharged into water bodies, because sewers are being put under great pressure by increased population. A lot of them are very old, over a hundred years old. And yet there is a big shortfall in funding, about $122 billion — that’s the estimated shortfall over the next ten years from the EPA.

The thing to me that is more surprising and more thought provoking than even the dreadful sanitation statistics in the developing world is the fact that we assume we’ve got is all sorted out. We haven’t either. That said, the flush toilet and the wastewater treatment paradigm has undoubtedly been an extremely good medical advancement and has saved lots of lives and probably added 20-30 years to the human lifespan. And it was the biggest medical advancement over the last 300 years by the Tisch Medical Journal. So I’m not trying to lessen it’s impact, the impact of the way we deal with wastewater. But I do think that it needs to be looked at again.

Are there any big issues you’d like to mention?

Well, seeing as you’re clean water people, I think another issue is that clean water gets much of the attention and you have a lot of celebrities who are willing to talk about clean water, which is great and I’m certainly not knocking that or the efforts of people working on clean water. Obviously that problem hasn’t been solved yet and is going to get worse before it gets better. But I do wish that someone would be willing to pose in front of a nice shiny latrine in a school somewhere in Africa, rather than just standing in front of a nice shiny tap.

Because I just think it just needs someone to step up and say “I’m not ashamed to talk about human waste,” because the health issues are just so phenomenally important that we just can’t afford to be prudish anymore. It’s just too late. Too late to be prudish. So that’s my clean water versus sanitation rant.

Can you speak a bit more about the significance of linguistics pertaining to sanitation?

Look at euphemisms. The last time we probably used a word that actually described the receptacle we need to dispose of our human waste, was probably in the 16th century when Henry the VIIIth had something called the House of Easements. I think that was the last, because ‘toilet’ is a euphemism. Toilet comes from French; it used to mean a dressing table. W.C. means water closet. Bathroom and restroom? I’m not even going to go there.

We just have led euphemism upon euphemism upon euphemism until we don’t really know what’s what anymore. And yet just the basic concept of providing citizens with a public bathroom, toilet, whatever, restroom is not common. I mean you go to New York or probably any other big city, there’s just none available. Or in London. And yet you don’t have anyone protesting about it. And it’s strange. We’re all so adaptable. We just kind of manage with a very imperfect situation.

C. T. Pope is a Circle of Blue writer and researcher. Reach him at circleofblue.org/contact.

Circle of Blue’s east coast correspondent based in New York. He specializes on water conflict and the water-food-energy nexus. He previously worked as a political risk analyst covering equatorial Africa’s energy sector, and sustainable development in sub-Saharan Africa. Contact: Cody.Pope@circleofblue.org

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!