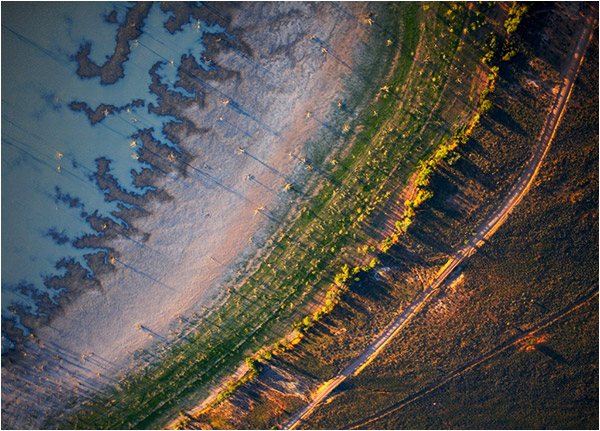

An Industrialized Nation Reckons With A 12-Year Drought In The Murray-Darling Basin

The skeletons of Australia’s iconic Red Gum trees haunt the shrinking shores of Lake Pamamaroo near Menindee, New South Wales.

by Keith Schneider

Photographs by J. Carl Ganter

Circle of Blue Reports

On a rainless afternoon in December, Bill Gread stands in the bright and hot sun near the southern boundary of Australia’s Murray-Darling Basin and eyes the sharp edge of an irrigation canal so new it has never carried any water. Gread, stocky and slow moving, wears heavy blue work pants and a blue shirt that show the dust and red clay of the irrigated dairy country in northern Victoria where he was born more than 70 years ago. The land and his farm have pulled at him so hard that he only recently left a hospital bed in nearby Shepparton, where surgeons performed a quadruple bypass. “Aah,” he says, laughing when asked how it went. “No worries.”

More important is showing visitors the irrigation canal that he built with the graders, backhoes and workers employed by the excavation company he also owns. Roughly 20-feet wide, five-feet deep and lined with white rock and clay to prevent leaks, the canal will direct water to narrower channels fitted with new gates. The idea is to be much more exacting in directing water to the alfalfa crops that Gread now grows in the fall and the spring. The seasonal rotation, unlike the year-long cropping pattern he just abandoned, also saves water, Gread says.

Taken together, these three changes – lined irrigation canals, smaller gates and seasonal crop plantings – will save at least 50 percent of the water that Gread’s farm once used. And though they may seem simple to understand and install, the upgrading of Gread’s farm is a microcosm of the powerful changes in agriculture and water use that Australian climate scientists and agronomists say are essential to the survival of agriculture in the Murray-Darling Basin.

This is no mere statement of hyperbole, scientists insist. It’s what happens when an agriculture industry purposefully designed to use an enormous amount of water collides with a hotter and dryer climate that produces much less rain. Bill Gread and the more than 60,000 other farmers in the Murray-Darling Basin are experiencing the same threat to their livelihoods as autoworkers in Detroit, or herders in Inner Mongolia. A resource-intensive way of life is crashing into limits on production that were long anticipated and are now arriving with dire consequences.

The average temperature in the Murray Darling Basin has climbed 1.6 degrees Fahrenheit since 1950, according to the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, Australia’s respected science agency. So much less rain is falling that surface flows across the basin’s nearly two dozen river valleys have been cut 40 percent, from 23,000 gigaliters to just over 14,000. The latter figure is just about the same amount of water that the government has allocated to the big and small towns across the basin, and to farmers who irrigate globally significant crops of rice, alfalfa, cotton, oranges, grapes, apples and vegetables.

Do the math. Towns and farms are using just about as much water as is falling from the clouds. Over the past decade there has been so little water left in the lower sections of the river system that for every four out of ten days, the Murray River doesn’t even have enough flow to reach its mouth in the Great Southern Ocean south of Adelaide.

The logical solution, of course, is to use less water. Bill Gread shrugs his shoulders when explaining this point. He tugs on a cable to lift a bright and shiny aluminum gate he’ll soon use to stingily direct water to one of his alfalfa fields. He says that in previous years a wider gate provided for flood irrigation to the field, not the quick on-and-off irrigation technique he will soon deploy. “Cut water use by at least half,” he says. “Maybe more.”

Whether that’s enough is not at all clear. Since the late 1880s, and with much greater vigor after World War Two, Australia lured its young men and their wives, among them Bill Gread’s parents, from the temperate coastal cities to settle the Murray-Darling River Basin’s forbiddingly dry ground. They and their heirs developed a US$30 billion-a-year farm economy, larger even than California’s, that reflects the wealth and bounty produced by soil, sun and hearty people.

Yet central to the Murray-Darling Basin’s business strategy lies a manifest agreement with nature common to all of farming, but especially meaningful in deserts. The quid-pro-quo for nations that ask their people to grow food where there’s so little moisture is that the rain will come and water will be provided. That agreement is not only broken across the 400,000-square-mile basin, which is larger than France and Germany combined – the question of whether it can be fixed is not at all assured. “Bloody drought,” Gread laments. “It’s got us good.”

When The Rain Stops

Twelve years ago, the rain stopped falling with any consequence in Australia’s prime food-growing region, bounded on the south by the Murray River and the west by the Darling. The clash between nature and agriculture in the Murray-Darling raised food prices and was widely followed in the news media by the rest of Australia.

But outside the country’s borders, this growing crisis was hardly known until last year, when the basin’s one-million-ton rice crop failed. Growers managed to harvest just 18,000 tons. The crop disaster wrecked the economies of Deniliquin and other rice-producing towns in New South Wales, one of the four states encompassed by the Murray-Darling Basin, driving families from their farms and causing suicides at twice the national rate.

Perhaps more significantly, the importance of the Murray-Darling Basin to the planet’s food supply emerged for the first time. The Australian rice failure was a factor in driving up prices that prompted global food riots in 34 countries.

This year, as the drought persisted and much of southeast Australia roasted in daytime temperatures that reached nearly 120 degrees Fahrenheit, the world paid more attention. In February, the worst fires in Australia’s history raced across the southern boundaries of the basin, killing 210 people.

Bill Gread is far from the only Australian who meets a question about the drought’s significance with a tight smile mixed with equal measures of tension and conviction. While it’s not much discussed, there nevertheless is an understanding among the country’s more than 21 million residents that just living in Australia comes with tangible everyday risks offered up by the environment. Australia is not only the driest inhabited continent on earth, it’s also one of the wildest and most remote. Deadly snakes are common in the south. Man-eating crocodiles inhabit the north. Divers visiting the Great Barrier Reef wear protective suits to keep from being stung by box jellyfish, which are difficult to see and so deadly that they kill by sending their victims into convulsions.

Perhaps that’s why Australians have with uncommon vigor pursued dominion over nature, and nowhere with more enthusiasm than in the Murray-Darling Basin. Over the course of a century, with a Victorian passion for engineering works, financed in part by British imperialist desire to water the desert to feed the empire, Australians dammed, straightened, controlled, stored and channeled the waters of 23 river valleys. Then they spread the water wealth to agriculture. More than half of Australia’s cereal grains, and most of its apples, grapes and oranges, are produced in the basin. Twenty-six percent of the nation’s dairy products come from the region surrounding Shepparton alone. Murray-Darling Basin farmers account for 70 percent of all the irrigation installed and used in Australia, and they generate 40 percent of the country’s income from farm exports.

Farmers here boast that they can feed 80 million people. And to some extent they do – when there’s rain. But when there’s not, the risks of living and farming in southeast Australia become readily apparent. Rural debt has nearly doubled over the last decade, according to the Reserve Bank, from US$20 billion to US$35 billion. Families are leaving, and enrollment is steadily declining in dozens of school districts.

The fixes are almost unfathomable for Gread and his neighbors. Essentially, all of the water-intensive farm practices that produced the Murray-Darling Basin’s bounty have to be seriously reworked. Cropping patterns. Irrigation practices. Technology. Water management systems. Infrastructure modernization. A good deal of the sprawling irrigation network may need to be ripped out. Some industries, like rice, may never recover.

A Warning On Food Scarcity

Perhaps not since the American Dust Bowl of the early 20th century has an industrialized nation sustained more damage from drought in a prime food-growing region than Australia. While it’s the first in modern times to be so heavily buffeted by drought, meteorologists insist that more primary food-growing nations will soon collide with similarly catastrophic weather.

One of the top researchers sounding the alarm is Julian Cribb, a journalist and professor of science communications at the University of Technology in Sydney. “It’s everything actually coming together at once that makes the situation more serious than people have taken it to be until now,” he says in an interview. “And rather much more urgent that it be addressed.”

Indeed, says Cribb, 2008 was the eighth year in a row that the world’s six billion people have consumed more food than was produced by farmers. There was just enough food in storage worldwide to feed the planet for about 55 days, according to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. That is less than half the supply of the late 1990s, and the lowest food stores in 37 years. The World Bank says 100 million more people are starving.

Harvests of grain, milk, and meat are crashing into new limits of production. The rising cost of fertilizer and the shrinking land base suitable for agriculture are two of the new limits. Another is the world’s population, which is projected to climb to 9 billion by mid-century. Fisheries are collapsing, putting more strain on land-based farming. Budgets for agriculture sciences are shrinking.

Yet in the face of these and other limits to production, global demand for food is expected to rise 110 percent over the next 40 years.

Yet arguably the most important new limit, says Cribb, is the competition for fresh water. For most of the last century, 70 percent of the world’s fresh water was used in irrigation. But within a decade or so, cities will command half or more of the world’s fresh water. Farmers won’t be able to turn to groundwater, because those underground reservoirs are falling in every country in the world where it is used for agriculture.

And on top of all of these trends is global climate change, which is steadily drying the planet’s major food-producing regions. “The volume of fresh water available to grow food is now in decline,” Cribb says. “And it is quite likely we will have to double farm output using only two-thirds of today’s water volume.”

The point, says Cribb, is that the world’s food growing regions, what he calls “food bowls,” are being forced to adjust to startling new and much dryer conditions. “The Murray-Darling Basin is a food bowl,” he says. “There are many food bowls like it. The Indus-Ganges food bowl in India. The Yangtze-Yellow River food bowl in China. The Volta-Chad food bowl in Africa. In almost every one of these cases, the rivers are in trouble. The rivers are being emptied, the ground water is being drained, the soils are drying out, the lakes are filling in with sediment. So in almost every one of these major river basins, particularly in the drier areas – that’s 25 degrees on either side of the equator – there is a diabolical problem emerging for the world. And we have to learn to manage these basins with much greater efficiency and sensitivity for the environment than we have now, or we are going to be in a lot of trouble.”

The collapse of Australia’s rice harvest is one case in point. Another is wheat. In the last two years, Australia’s wheat growers managed to harvest just over half of the 20 million tons of grain they normally produce. Australia is the world’s sixth-largest exporter of wheat.

This year, Argentina, the world’s third-largest exporter of corn, is experiencing the worst drought since 1971. The corn harvest is expected to drop 25 percent. Soybean production also has been cut significantly, and the wheat harvest looks like it will be about half its usual size. The price of corn has climbed 50 percent. Soybean prices are up 40 percent.

California agriculture also is in peril. A two-year drought has reduced the Sierra Nevada snowpack, which provides water to Central Valley farms, by 40 percent according to the U.S. Geological Survey. Food production in the north Indian plain, central Asia, and China also are in peril as the Himalayan glaciers, the primary source of water for the region’s major rivers, melt away.

An Engineering Feat That’s Not Working Well

The city of Shepparton, which was settled in the 1850s, stands on the banks of the Goulburn River, surrounded by the irrigated high ground of northern Victoria. Less than 50 miles downstream, the narrower Goulburn reaches the wide Murray River in Echuca, where the larger river bears evidence of the flat sand and clay region it drains. The Murray is sluggish, deep, and dark. Hundreds of miles further downstream, the winding Murray converges with the Darling River at Wentworth, and from there it’s another 300 miles to the sea.

If the same conditions existed today that greeted the city’s settlers back in the late 19th century, the Goulburn and Murray in December, January, February and March would be shallow and lazy in the heat of Australia’s summer. In the winter and spring, it would be full-bellied, deep, and muddy. Today, both rivers behave and look like big irrigation canals, which is essentially what they are – full of water, slow moving, and the color of black tea, summer or winter.

How Australia gained such control over the waters of the Murray-Darling Basin bears some scrutiny. In 1884, following a seven-year drought, farmers, businessmen and provincial government officials began collaborating to contain the natural flow of the Murray. A delegation was sent to California to study the early engineering of the dams and aqueducts that stored the snowmelt of the Sierras and irrigated the flat fields of the Central Valley. George and William Chaffey, Canadian-born brothers who had helped design and build the California irrigation network, were hired to duplicate the feat, starting in 1887 on the lower Murray River around Mildura.

Over the next 100 years, more than 30 major dams and reservoirs – and 120 other smaller weirs, locks, basins and other water management projects – were constructed, first on the Murray and then along every other major river, and many minor ones in the region. The waters of what was once a vast and free-flowing network of indolent rivers that regularly flooded into abundant wetlands, and teemed with fish and wildlife, are bound up.

In the context of the values and principles of the 20th century, the corralling of the waters of the Murray-Darling Basin represents a high achievement of engineering and public policy in pursuit of monetizing available natural resources. Government and private business collaborated in building and operating one of the largest irrigation networks on earth. It was only much later that the costs to the environment – and by extension the quality of life and the tourist economy – became clearer.

Accompanying the water works were laws and agreements giving states – and most recently, the federal government – authority to decide who gets water and how much. Among the most important of these was the first River Murray Water Agreement, reached in 1915, that authorized three states – New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia – to coordinate construction and dispense water from the Murray, the Darling and the Murrumbidgee rivers. Two years later, the states established the River Murray Commission to carry out the agreement.

In the seven decades that followed, until the last major dam was completed at Blue Rock Reservoir in 1984, the framework of the 1915 agreement assured two basic outcomes. The first was to store the equivalent of three years of rainfall in the reservoirs and catchments. The second was to allocate water for use, 90 percent of it by farmers, and the rest for the growing farm and river towns that developed. The intent was to collect and deliver as much water as possible to agriculture.

The system worked so well that in the wet middle part of the 20th century, Australian authorities began describing the Murray-Darling Basin as “drought proofed.” The droughts that occurred generally didn’t last long enough to empty the storage basins. And even if they did persist, the water authorities could reduce allocations sufficiently to encourage farm practices that temporarily conserved water.

The extensive investment in infrastructure and management had a purposeful effect on the land and the economy. The number of farms increased. Water use tripled, from under 3,000 gigaliters in 1920 to 13,000 in the late 1990s. Shepparton, a city of nearly 40,000 residents with broad boulevards and an active downtown, is evidence of the wealth and cultural steadiness that comes from turning a desert green.

Trouble

About 20 miles outside Shepparton, Bill Gread’s farm stretches out in 40-acre square paddocks, each surrounded by low earthen berms. Four paddocks, one after the other, lie alongside an irrigation channel connected to the new main canal. When the paddocks were built decades ago, says Gread, there was enough water to plant crops year round, flooding the paddock, and then allowing the water to drain onto poor ground or into groundwater.

“Now we store what’s not used over there.” Gread points to a large pond, ringed by earthen walls. Irrigation water, which used to flow through Gread’s farm only once, now circulates until it’s used up. Gread explains the new approach while a neighboring cattle producer, Dudley Bryant, gets closer to listen.

“We’re horticulture and dairy here,” adds Bryant, who’s 58 years old and whose political activities associated with reducing the consequences of the drought on agriculture have made him one of the most well-known farmers in Victoria. “We see a future for us with this fast-flow irrigation. I think for rice, cotton, those sorts of crops – they’re probably more looking at losing a year or two. They don’t have to sow every year. Whereas, with a dairy farm or a fruit farm, you can’t choose that option. You can’t just sell your cows and say, ‘I’ll get ’em back next year.’ So the drought does change your thinking a bit.”

Bloody drought. It’s got us good.

The same applies to the entire region. When the drought started in the late 1990s, there was no indication that it was anything other than a typical interruption in the largely rainy weather pattern that had persisted in the Murray-Darling Basin for the previous 40 years. The ample moisture had encouraged more farming, and more water use, under a system of permits and licenses and allocations managed by the state governments. There are 24 different kinds of permits and licensing agreements, and each one carries a right to gain a share of the basin’s water.

Promising Water That Can’t Be Delivered

While complex and often cumbersome, the system worked well in the wet years when the basin gained 23,000 gigaliters of water each year, reservoirs were full, and the government allocated 11,500 gigaliters to farmers and cities. Mightily productive farms and extremely water-intensive farm practices developed that filled stores, but also tested the limits of industrial arrogance. Desert dairy producers flood-irrigated alfalfa. Australia encouraged huge harvests of rice and cotton, which use more water than any other crops.

The drought, though, has reduced the water flows in the basin from 23,000 gigaliters to under 14,000 gigaliters, or roughly as much water as authorities have allocated for agriculture and other uses. The result is that the era of profligate water use is done for now, and if climate specialists are right, likely forever. The drought has forced state water authorities to slash allocations to farms to as little as 4 percent of the normal amount in the rice-growing regions, not enough to raise a crop, and from 10 percent to 40 percent of normal allocations in other regions. Moreover, say Australian scientists who developed surprisingly accurate computer models, the rain-scarce weather pattern is likely to remain the norm.

The effect on the landscape is not subtle. The network of manmade lakes south of Shepparton is closer to empty than full. Amber signs flash alerts along the region’s roadways, keeping residents abreast of reservoir levels and warning people not to waste. Melbourne and Adelaide, two of the country’s largest cities, are running out of water. The basin’s ecological health – its birds, fish, mammals, trees and soils – is steadily deteriorating. The arcane deliberations by government authorities who tally water levels and issue formal orders about who gets how much are as closely followed across the four states as the stock market is in America.

In the parlance of water specialists, the Murray-Darling is “over-allocated,” which means more water has been promised to farmers and cities than the system produces. The problem for Australia, and by extension the world, is to chart a new course that assures the supply of water is adequate to meet competing demands – including sustaining natural systems – and still produce enough food. Solving that challenge represents one of the biggest tests of Australia’s competency and capacity to change in its history.

A Response of Politics and Policy

To date, the states and the Commonwealth have treated the problem as a matter of policy debate and investment. In 1992, almost in anticipation of the rigorous test to come, the Commonwealth and three states approved a new agreement for sharing the waters of the Murray-Darling Basin with a big new focus: making sure enough water was directing to sustaining the region’s environment. For the first time, the 1992 pact also began to take a serious look at putting limits on the amount of water available for agriculture.

In 2004, the Commonwealth passed the National Water Initiative, which directed water managers to specifically address issues of allocation, set timelines and deadlines for changes in management practices to conserve water, and make sure the environment received a fairer share of available water. Perhaps the most important provision of the law was to enable farmers to more easily sell and trade their water rights on the market, clearing a path for government to buy water rights.

Three years later, in the 2007 National Plan for Water Security, the Commonwealth proposed to spend US$7 billion over the next decade to assure that businesses and communities would have enough water. About US$700 million would be invested in desalinization plants for thirsty cities. The balance was directed at the Murray-Darling Basin: US$4 billion to modernize irrigation systems and practices, and US$2 billion more to buy water rights, and water, for environmental restoration.

In 2008, Australia’s new Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, introduced his “Water for the Future” program to increase the spending on water security to nearly US$9 billion.

In addition, the state of Victoria and Melbourne established separate management and spending plans, at a cost of US$3.5 billion, that are designed to secure Melbourne’s water supply. Most of the money is being spent to build the world’s largest desalinization plant south of Melbourne. But roughly US$1.2 billion is being invested in modernizing the 4,100 miles of irrigation canals and channels to significantly reduce seepage and waste in the Goulburn-Murray irrigation district, and to build a disputed pipeline from the Goulburn River to supply a portion of Melbourne’s water. The irrigation canal that supplies Bill Gread’s farm is a tiny part of that plan, known as the Northern Victoria Irrigation Renewal Project.

Disagreement

Such significant investments and changes in government policy have prompted a new wave of political dispute in Canberra, Australia’s capital, and in the Murray-Darling region. Farmers and environmentalists are scrapping over how much water should be directed to restoring fisheries and wetlands, both of which have been decimated by dams, channels and the drought. Farm families face life-rending decisions about whether to sell their water rights – at prices that can earn them US$250,000 or more – to a government eager to buy them but difficult to work with.

We’ve got to punch through the negativity and show you can operate in a constrained environment and can operate profitability and have a business that’s worth passing on to your kids.

Farm communities worry that if enough producers sell, farm productivity will sag and with it the number of good farm-related jobs and economic sustainability. Though the Victoria irrigation project is designed to conserve more than 10 percent of the water now flowing through the Goulburn-Murray district, many of northern Victoria’s farmers still look unfavorably toward Melbourne taking a third of that water from a water-scarce region. And it’s certain that some, perhaps many, of the outlying sections of the Goulburn-Murray irrigation district will no longer be served with irrigation water.

At the center of the tumult is Murray Smith, the chief executive officer of the Northern Victoria Irrigation Renewal Project. Smith gained the post because just prior to joining the Victoria irrigation project, he led the modernization of the Coleambally irrigation district, a much smaller system that serves 437 farms across the Murray River in New South Wales. As part of that project, farm practices also were improved to conserve water. When the Coleambally project was finished, the system was so efficient that farmers had extra water, which they could sell. Last year, water sold for over $1,000 a megaliter. Two megaliters are equivalent to the amount of water it would take to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool. Many farmers had over 150 megaliters to sell, according to Smith.

“At US$1200 a megaliter, they were able to sell that water without taking a tractor out of the shed, and they made a significant windfall,” says Smith, who is certain that once northern Victoria farmers see they can produce more with much less water, resistance will subside.

“We’ve got to punch through the negativity and show you can operate in a constrained environment and can operate profitability and have a business that’s worth passing on to your kids,” Smith added. “This is happening on a large scale. And it’s happening in a time where we are under the pump. We’re under a lot of pressure to deliver.”

Will It Work?

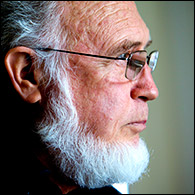

No doubt, US$12.5 billion is a lot of money to invest in conserving and managing water. But government authorities say they are prepared to spend even more. Before he retired in 2004, John Williams, the white-bearded former chief of land and water for the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, played a huge role in pushing Australia to respond to the deepening drought. In an interview, Williams says that a new moment of reckoning for the country has arrived and that the new policies may not be enough for the Murray-Darling Basin.

“So we have a major adjustment to make,” says Williams. “This basin is over-allocated. We must reset it. We must help communities to adjust to living with 60 percent of the water we’ve had in the past. That’s urban communities and rural communities both. We must be brave about that, and take on the social issues and the political issues and make the change. If we do that, I believe we can, turn it around.”

This basin is overallocated. We must re-set it, we must help communities to adjust to living with 60% of the water we’ve had in the past, and that’s urban communities and rural communities both. We must be brave about that, and take on the social issues and the political difficulties and make the change.

This basin is overallocated. We must re-set it, we must help communities to adjust to living with 60% of the water we’ve had in the past, and that’s urban communities and rural communities both. We must be brave about that, and take on the social issues and the political difficulties and make the change.— John Williams

Williams insists, in essence, that agriculture in the Murray-Darling Basin cannot thrive, and may not survive, unless production tools, crops and techniques are more quickly developed to better fit the region’s distinctive conditions, especially the scarcity of fresh water.

That idea has quickly elevated to national prominence. In a paper in September for the Australia Conservation Foundation, researcher Andrew Campbell wrote that the basin’s challenge is to develop “farming systems that are more intrinsically Australian.”

His definition, which could apply to all of global agriculture, is food production practices “that are resilient in the face of extreme weather and extreme seasonal variability; that are miserly with water and conserving of energy; that maintain groundcover and are kind to the soil; that sit lightly on the landscape and don’t displace native wildlife or habitat; that are highly profitable in good seasons and don’t lose money in bad seasons; that preserve and build their natural, human and financial capital; that recover quickly from shocks and stress; that attract and retain young, talented people on the land; that generate jobs and income in regional communities; and that produce things in high demand for good prices.”

The new irrigation canal on Bill Gread’s farm is one piece of the more intrinsically Australian agriculture. Other steps include reducing energy use in agriculture, among them developing better sources of soil nutrients that are not nearly as reliant on expensive and increasingly scarce petroleum. Another is basing more of the country’s cuisine on fruits and vegetables instead of animal products requiring crops, like alfalfa, that use more water. And there is a continuous need to vastly improve the efficiency of irrigation and still achieve high crop yields.

Australia has started down this path. “We’re doing things differently now,” says Gread.

Julian Cribb asserts that Gread and the Murray-Darling Basin’s producers have no time to lose. “The ideas that will come out of the Murray-Darling Basin are the ideas that will help to save the Indus-Ganges Basin, the Tigris-Euphrates Basin, all the places where we grow grain and we’re short of water,” he says. “So I believe this is going to be a source of knowledge, a source of hope. The experience here – a hard-won experience, at a very high price in human suffering – nevertheless is going to be vital knowledge in sustaining the human food supply through the absolute peak in human numbers and demand in the middle part of this century.”

Keith Schneider, a former New York Times national correspondent, is senior editor and producer at Circle of Blue. J. Carl Ganter, an award-winning photojournalist, writer and broadcast reporter, is the co-founder and director of Circle of Blue. Reach Schneider at keith@circleofblue.org and Ganter at carl.ganter@circleofblue.org. For a complete list of credits, acknowledgements and other resources related to Circle of Blue’s coverage of “The Biggest Dry” please click here.

Circle of Blue’s senior editor and chief correspondent based in Traverse City, Michigan. He has reported on the contest for energy, food, and water in the era of climate change from six continents. Contact

Keith Schneider