Present U.S. Water Usage Unsustainable: An Interview With Dr. Peter Gleick

In an interview with Circle of Blue, the Pacific Institute’s Dr. Peter Gleick discusses water resource challenges the U.S. faces in the near future. As co-founder and president of one of the nation’s leading water think tanks, Gleick served as an academician at the International Water Academy in Oslo, Norway in 1999 and was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2003. He was also elected to the National Academy of Sciences in Washington D.C in 2006. Gleick currently serves as a science advisor for Circle of Blue. For partial audio excerpts of this interview, click here.

We’re coming into the summertime, which is traditionally when we have droughts, fires, and fads in the media covering water. What are the big issues facing the U.S. regarding water coming into this summer and even in the next three to five years?

I think we see a lot of interest in water. At the moment not just because it’s the summer and because summers are hot, but because this appears to be a particularly dry summer in many parts of the United States. We are in an officially declared emergency drought in California. The Southeast continues to be dry; the reservoirs in the Southwest around the Colorado River have been dry for many many years now. I think what we’re seeing is a combination of events that for water means we’re moving into a new era of water crisis. We are moving into a new era where we can no longer take water for granted.

Here in the US water is a challenge that has mainly been seen as “over there” in Africa, in Southeast Asia, but we’ve seen a lot of dots growing on the U.S. map. What are we missing here in the United States, what’s the big story?

We’ve done a great job in the United States in reducing our vulnerability to drought by building massive infrastructure for storing water in wet periods, so we can use it in dry periods. The downside is it’s made us in a sense ignore water as an issue for far too long. We now see growing water shortages not just in places that we used to think were dry, but in places that we used to think were wet. We’re ignoring the way we use water. We’ve stopped thinking about how to use water efficiently and effectively because we’ve always assumed that it would always be there. That no longer is the case. We’re moving into an era truly I think of water scarcity throughout the United States and that by itself is going to force us to move to an era of more efficient management techniques.

In the United States, where are we going to be with water five years from now?

There are two ways to answer that. If we continue along the path we’re on, if we continue to do things the way we’re doing them, we’re going to be much worse off in five years, ten years, or in the coming decades because the way we manage water now is inappropriate. It’s not sustainable: we over-pump our groundwater and we take water from ecosystems. We don’t think about how we grow and where we grow our population; so the business-as-usual future is a bad one.

We know that in five years we’ll be in trouble, but it doesn’t have to be that way. If there was more education and awareness about water issues, if we started to really think about the natural limits, about where humans and ecosystems have to work together to deal with water, if we were to start to think about efficient use of water, we could reduce the severity of the problems enormously. I’m just not sure we’re going to.

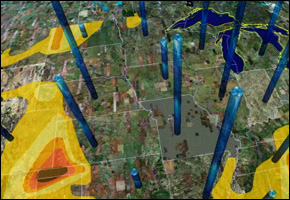

Taking a look at the map, a study several years ago said at least 36 states will face severe water challenges within the next ten years. Where are those challenges and what do you see as potential impacts of those challenges to policy, population, industry, and economics?

There was a US government study by the Government Accountability Office just a few years ago looking at possible water scarcity risks in the future, and one of the stunning findings was that they concluded 36 states anticipate having serious water shortages in the near future. That didn’t include a whole series of states that failed to respond including California, Arizona, and Nevada; states that we also know are going to be on the list. But even more stunning I think was the realization that the places that we expect to see serious water problems are not just the traditional ones where we expected to see them–not just the Southwest, but the United States as a whole. Every region of the United States is vulnerable to water problems: water scarcity, water stress, and water contamination.

We see problems around the Great Lakes with allocations of water. We see growing political problems: U.S. and Mexico relations on the Southwestern border and the U.S. and Canada on the Northern border. We see contamination problems throughout the Northeast. We see terrible contamination throughout the Southeast where water has always been relatively abundant. There’s the long history of traditional problems in the Western U.S. It’s no longer a regional problem. It has become a national problem.

What’s the tipping point to put this on the political agenda, or the response agenda?

I think we’re slowly seeing a tipping point. I think we’re seeing growing awareness of water problems in places that didn’t have it in the past. Maybe what’s going to come with that is the realization that no place can take water for granted; that we cannot take water for granted anywhere in any form in the U.S. There are already some growing calls for better management throughout the U.S. There is some interest in having a national reassessment of our national water policy, which is long overdue. We haven’t really thought about water at the national level since the 1970’s and the world has changed enormously in the last forty years. I think we’re at the point now where there’s an opportunity for new kinds of communications, new kinds of actions, and new kinds of thinking about water.

Do you see water becoming a major topic in the election?

The environment has never been a prime election issue, ever. There are always things that dominate the story, dominate the interest above the environment; but having said that, the environment is always high in people’s thoughts. The environment is always an issue that people care about and I do think we’ve suffered neglect during the last eight years.

I think the current administration has, in the water area, hugely neglected both the risks and the opportunities. We’re seeing serious water contamination problems, serious water scarcity problems that could have been avoided had we taken action over the last decade and we didn’t. I think there is a chance that the next administration will change the tone no matter who it is. If they don’t change the tone, I think we’re heading for a wall. We’re heading for very serious constraints on the things that we can do with the water resources that we have.

Where will those constraints take hold?

I think we’re facing serious constraints on the kinds of things we can do with water, if we don’t move to a new path. Those constraints are economic because everything we do in our economy requires clean, safe, available water. I think they’re environmental because we’re learning that our environment is incredibly sensitive to both contamination and overuse of our water. They’re social and they’re political constraints. When we don’t have enough water to do the things we want, people care; people care a lot. And that’s going to feed back into politics. It’s going to feed back into our everyday lives.

Interview by J. Carl Ganter for Circle of Blue, June 20, 2008

Circle of Blue provides relevant, reliable, and actionable on-the-ground information about the world’s resource crises.

California has to address the huge disconnect between state and local water agencies and local governments. While the water agencies are warning of massive drought conditions and asking customers to cut their water use, local governments continue to sign off on massive new sprawl housing subdivisions in the hotter parts of the state that are bound to increase statewide water demand. The water agencies currently charge residential customers tiered rates to encourage conservation, but refuse to adopt tiered rates for commercial, governmental and ag customers, charging them the same no matter how much water they use.